The people’s voices in the story of the Marawi siege were hardly heard, drowned out by the sounds of war, but if the media had reported the story differently, more lives could have been saved and a humanitarian crisis could have been averted.

“The attention of media went to the conduct of war but the history and life of Marawi City, which was the center of the conflict, was not in the news,” Marawi resident and civic leader Samira Gutoc-Tomawis said.

“If media tracked down Marawi’s past and the roots of its people’s resistance to violence, media could have understood the siege better and they could have saved lives,” she said in a phone interview.

Journalists covering the Marawi siege. (File photo by Luis Liwanag)

Gutoc-Tomawis, who leads the Ranao Rescue Team, made the observation as families displaced by the conflict were slowly rebuilding their lives one year after the southern city was turned into a battleground between government troops and local terror groups with links to foreign Islamic militants.

Lamenting that “media told very few human stories, or they did not tell the story at all,” Gutoc-Tomawis cited the case where about half of some 250 pregnant Bangsamoro women gave birth prematurely in difficult conditions because of stress and fear caused by the siege.

She said there were no media stories about them that could have prompted immediate help from government or private individuals.

“The media coverage could have saved a life though small things like calling the attention of medical professionals, asking for an ambulance from Iligan City where almost everyone was headed during the exodus, telling people about an information system that can pinpoint access or a hotline that could alert authorities,” she said. “Until today, there is yet no functional hotline.”

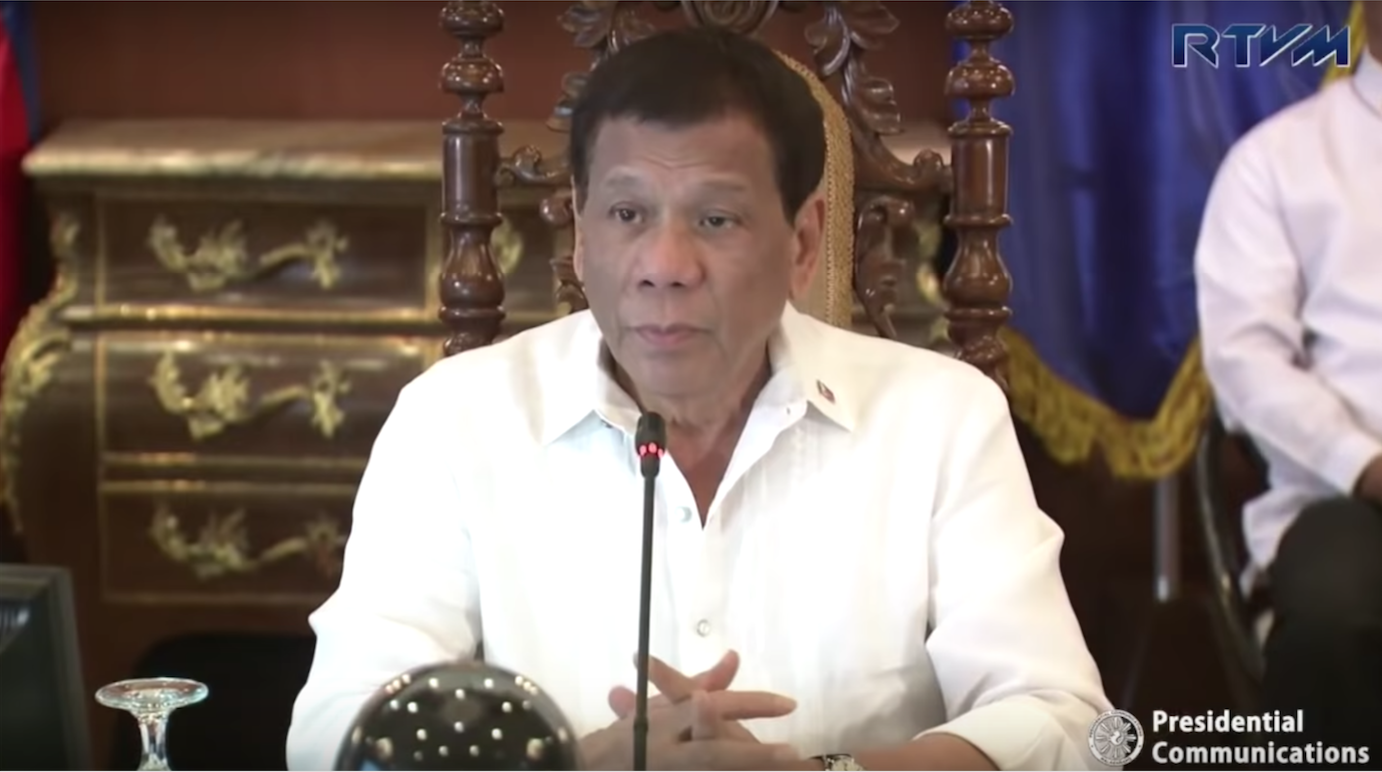

The conflict that ravaged Marawi resulted in the deaths of over 1,000 people – civilians and combatants from both sides. It prompted President Rodrigo Duterte to impose Martial Law over the entire Mindanao region. Congress approved its extension till the end of 2018 so the military could “eradicate the terror groups.”

Gutoc-Tomawis first shared her observation during a forum last month on ‘Media on Marawi: Coverage of the Siege’ organized by the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR), where she said the news and images were mostly of explosions and phalanxes of soldiers, with the exodus of people fleeing the war in the background.

Evacuees endure the heat inside the Gomampong D. Ali Cultural Center in Balo-i town, Lanao Del Norte. (File photo by Erwin Mascarinas)

In the April 26 forum, the CMFR presented its findings of its quantitative — through column space and air time — and content analysis of media coverage of the siege from May 23, 2017 to October 31, 2017 by newspapers with leading circulations and news broadcasts of four major networks.

Three themes — conduct of war, aid and support for afflicted communities and Martial law in Mindanao – dominated pages and airtime of the media covered by the CMFR content analysis.These were the Philippine Daily Inquirer, Philippine Star and Manila Bulletin and free TV’s news broadcasts TV Patrol of ABS-CBN, 24 Oras of GMA-7, Aksyon of TV5 and News Night of CNN Philippines.

In print media, the banner stories and front pages further focused on security measures, government policies on rehabilitation, politics, awards and memorials for soldiers, stories on the Maute group that led the siege, solidarity for the military and the government, price freeze, ISIS, CPP-NPA-NDF, calls for peace, while background on Marawi was the last on the list.

In broadcast media, the list is almost similar. In October 2017, there was a rise of visual stories of victory and peace, containing interviews with evacuees and ceremonial appearances of public officials after the siege was declared over.

CMFR executive director Melinda Quintos-de Jesus told the forum that the fighting or the conduct of war was highest in the list but there was very little else in the context of the society that was afflicted by the war or the affected communities which were the heart of the matter.

“Conduct of war was the most reported theme in the front pages of the newspapers reviewed. Afflicted communities/evacuation combined were second most prominent subject, but lower by more than a half of the number of reports on the ground operations. The third was martial law.”

While there were stories about refugees and internally displaced persons or evacuees, these were episodic; information did not reflect a data system, said the CMFR report. Human rights issues were raised in the stories about the loss of homes, damaged livelihood and alleged illegal arrests, human rights violations of the Maute group, including the use of human bombs, child warriors and forcing hostages to take arms and when martial law was declared and extended.

The content analysis showed that all the top 15 sources for stories in print media are from the government: eight from the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP); five from national government; one from local government and one from the Philippine National Police. The top 10 sources in TV were also from the government: five from the military; three are from national government; two from local government.

Journalists present at the forum welcomed CMFR’s review of the media’s coverage of the five-month conflict and acknowledged what was lacking in the reporting. Froilan Gallardo of MindaNews said media was not fully aware of the history of Marawi. “There are still so many questions.”

One other factor that affected media’s reportage was that their coverage, including accreditation and entries to Marawi, was controlled by the military, an issue that had on occasion put journalists at odds with the military.

Former AFP spokesman Restituto Padilla said this is always the case during war and conflict. “We have our own protocols to the consternation of the media. But our aim is for their protection and safety as well as that of the public’s.”

The journalists said there were a few human interest stories during the siege, but these were reported much later. “I think what happened was that the event had to sink into our minds. Only then did the media realize that the story that was unfolding was bigger and had many dimensions,” Gallardo said.

“Marawi will be an unfolding story for years to come,” he added.

The CMFR said that due to lack of information on the international dimensions of terror threats or the formation of a supposed ISIS cell in the Philippines, the Mautes remained as much a mystery to the public as before the siege.

De Jesus said the Marawi conflict should not be relegated to the past as a news event; it should be reviewed for lessons learned and insights gained. For journalists, it should add to a learning curve, how better to report such conflict so as to avoid its re-occurrence. She said the media review helps to discover what was missed, what nuance was lost, what complexity was over simplified.

“Journalists will remember Marawi as part of a chain of conflict from the Zamboanga siege in 2013 and Mamasapano in 2015. Each of these episodes occurred in a season of relative peace which was assisted by efforts of the military. Each showed groups of Moros as the “enemy” — the one to fight,” she said.

In the Marawi siege, Filipinos also saw so many of their Moro countrymen suffer as victims, losing their homes, fleeing for their lives, not knowing whether they would ever return home.

As the rehabilitation gets underway in Marawi, De Jesus asked journalists to expand their scope of coverage of conflict and war and transform their reportage of Mindanao into something more about the people in a post-conflict situation.