With six deaths and hundreds injured, the bloody opening salvo of the First Quarter Storm in January 1970 both riled and excited President Ferdinand Marcos. But he cannot appear to give in to both sentiments. His plans for a one-man rule restson how well he handled himself in public and capitalized in the ensuing chaos.

The first impulse was to lie. Marcos had to put up a facade that his government was unrattled and magnanimous in the face of the hostility of youth activists.

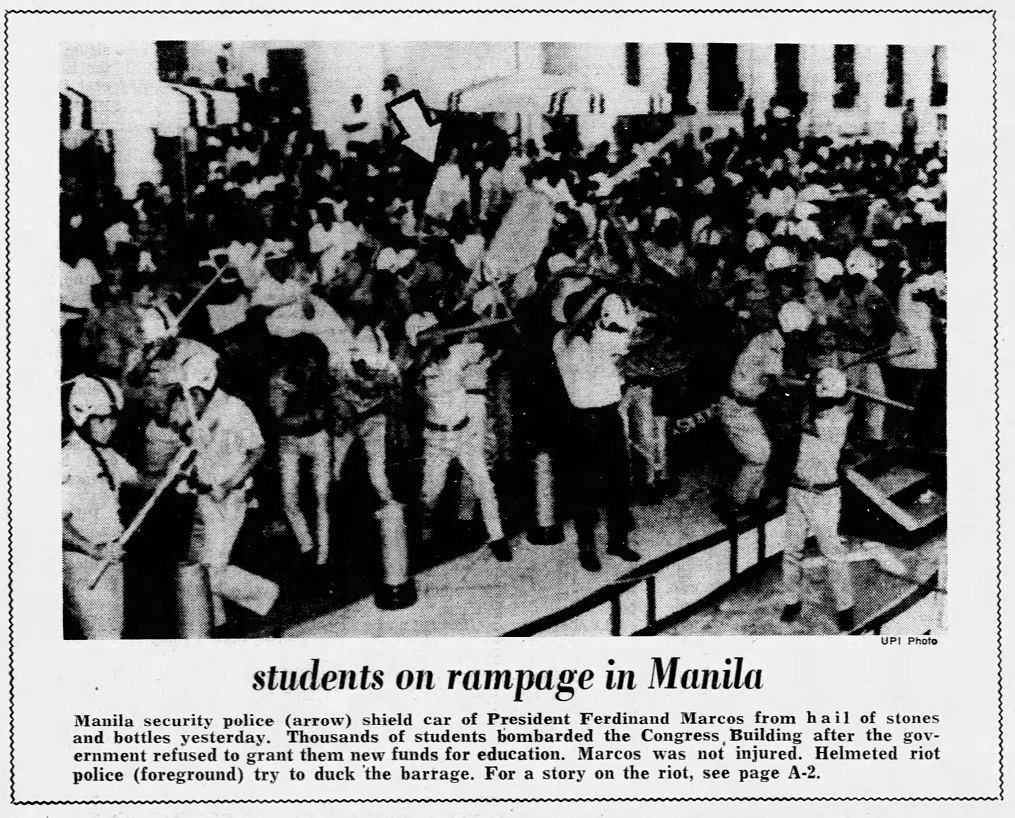

On March 5, 1970, Marcos’s interview with Nick Joaquin, aka Quijano de Manila, came out in the Philippines Free Press. Marcos admitted that on January 26, 1970, after delivering his State of the Nation Address, a cardboard coffin and a papier-mâché crocodile were thrown his and Imelda’s way on the steps of Congress. But what of the bottles and stones? “[I]t was originally not intended against the First Lady or me but against the police.” As their car sped away, “students were waving their hands at us. I was therefore surprised when I learned that there was a riot after we left.”

Marcos “was booed by demonstrators as he emerged from the [C]ongress building.” He was also booed when he came in, as noted by the journalist Hermie Rotea in I Saw Them Aim and Fire.

Had Marcos written the history of that fateful day, there would have been a lovefest and an adoring crowd as he and the first lady came out of Congress, instead of protest by up to 50,000 demonstrators (according to media accounts).

“The First Lady was … busy shaking hands with everybody, including the students. I was also shaking hands with students, first in the lobby, then on the stairs, then on the sidewalk. We were hemmed in by students; we were shaking hands with them. Everybody wanted to shake hands with us.”

A United Press International photo published in the January 27, 1970 issue of the Honolulu Advertiser makes one wonder when all the glad-handing could have happened as a phalanx of policemen immediately surrounded the First Couple as they exited Congress.

Photo by United Press International

From Rotea:

[A]s President Marcos and the First Lady were being escorted by security aides to their waiting limousine, stones, empty bottles, sticks, placards and other projectiles were thrown at their direction.

Alert security men immediately formed a human cover to protect the First Couple from the “flying missiles.” Fearing an assassination, Col. [Fabian] Ver pushed them into the car. His men covered the limousine from top to the sides and practically hid it from sight.

Fabian Ver, Marcos’ confidant and chief of praetorian guards, may have instinctively thought it was an assassination because that was what his boss often had in mind.

In a January 23, 1970 entry in his diary, Marcos cited Ver’s idea to “meet force with force and that the conspirators be eliminated quietly before they prejudice our country and democratic institutions.”

The Backlash of the 1969 Presidential Election

Ver and Marcos were not referring to the student demonstrators who in a week’s time would breach Malacañang’s Gate 4. They were talking about partisans of Sergio Osmeña Jr., the losing presidential bet in the 1969 election who they suspect to be planning a coup, if not the president’s assassination.

As pointed out by William Rempel in Delusions of a Dictator, Marcos was “troubled” by the “American rumor. The one suggesting that the U.S. embassy was secretly supporting advocates of a coup attempt” against him.

Still, Marcos demurred on Ver’s plan, insisting they instead “obtain evidence to prosecute them in court.” He feared that if he went with Ver’s plan, they “may unleash a wave of violence [that they] may not be able to control and do greater damage to our freedoms.”

Then the First Quarter Storm broke. Entries in his diaries and his public statements indicated a Marcos enticed by the violence he helped unleash, lusting to implement his “final solution,” the imposition of martial law. Which he almost did during the January 30, 1970 siege on Malacañang.

In Dead Aim, Conrado de Quiros credited Brig. General Rafael Ileto, then commanding general of the Philippine Army, for dissuading Marcos from imposing such draconian measure, explaining how unprepared the armed forces were to execute such a plan.

Marcos himself noted in his February 22, 1970 diary entry that he and his top military men were of the “unanimous assessment . . . that the subversives have no capability of mounting an attack of company proportion [a fraction of the total number of state enforcers around Malacanang during the Battle of Mendiola] and will not but are capable of small unit harassment.”

What he did not mention, but were brought up by de Quiros and Rempel, was that besides the police and the military, there was the immediate presence in the palace of armed Ilocano warlords and their bodyguards. Congressmen Roque Ablan Jr. and FloroCrisologo, Rempel surmised, did not only offer moral support, but “machine-gun support” as well.

Marcos may have the loyalty of the Ilocano politicians but not the full support yet of the military. Despite his fear for his life, Marcos could not give himself emergency powers just yet. Until then, his pretense at keeping faith with the country’s democratic institutions must be kept. In public, he conjured confidence and contrition; in private he wrote of spies and saboteurs—including the very ones he claimed to have fielded to sabotage the opposition.

This was the mind of a man who just a month earlier achieved a unique feat in the country’s postwar history. He got himself reelected as president. He bested Osmeña with 1.8 million votes. On December 30, 1969 he was sworn in at the Quirino Grandstand for a second term.

Two years into his first term as president, Marcos started planning his 1969 re-election campaign. It was to be a violent and expensive campaign. So violent that during the election campaign, assassins lurked in Marcos’s mind. At election’s eve, Marcos confided to Joaquin that a Huk commander is after him. Before that, a group of 60 Muslims in Cebu. At that point, Marcos could simply have conjured enemies, both to show bravado and justify the violence inflicted on his opponent.

What was not imagined was how Marcos pillaged the public treasury for his reelection. As recounted by Raymond Bonner in Waltzing with a Dictator:

Two weeks before the election Marcos’s campaign manager, Ernesto Maceda, withdrew 100 million pesos (roughly $25 million). Then, with an air force plane and military security, he hopped around the islands, dispensing peso-filled envelopes: Barrio captains received 2,000 to 3,000 pesos, mayors up to 100,000 pesos, and favored congressional candidates as much as a million pesos. “We were prepared to cheat all the way,” Maceda said in an interview many years later.The election cost Marcos a staggering $50 million, which was $16 million more than Nixon had raised for his successful presidential bid the year before . . . . What votes Marcos couldn’t buy, he stole . . .

Marcos had the special forces of the Philippine Constabulary do the dirty work for him. They were under the command of Brig. Gen. Vicente R. Raval. The same police general would figure in the bloody events of January 1970. The flagrant electoral violence they committed put into question the legitimacy of Marcos’electoral victory.

Raiding the nation’s coffers tanked the economy. As he started his second term, Marcos stopped all government infrastructure projects as his government had almost ran out of money.

A month later, on January 26 and 30, activists, mostly university students, were to lay siege to Malacañang. Their protests exposed Marcos’ venality and sheer greed for power. In Marcos’mind, wrote Condrado de Quiros, “. . . when the students attacked Malacañang, they ceased to be only students . . . Behind them, he saw variously the NPA, Sergio Osmeña’s assassination squads, Ninoy Aquino’s private army, the Liberal Party, and the communist-infiltrated media, all carrying out a preconceived plan of action.”

Marcos limited his movement to the presidential palace in February that year, though Joaquin claimed “he traveled to Ilocandia to face another kind of demonstration: a public avowal of Ilocano affection” on the last week of that month.

Marcos’s ego seemed to be in need of constant tending. On February 6, when he started receiving visitors again, the Official Gazette said the first one was a large delegation of veterans who formally pledged support, “reiterating their faith in the leadership of President Marcos.”

The next visitor was former ambassador Amelito R. Mutuc “who, along with seven of his nine children, staged a ‘demonstration’ at the Freedom Park in front of Malacañang.” Mutuc told Marcos that he “was just showing my children, Mr. President, how to conduct a peaceful demonstration.” The day of adulation ended with Marcos receiving “500 copies of the book Ferdinand Edralin Marcos,” written in Ilocano by [Placido] Real.

In March 1970, Marcos went out of the presidential palace six times, spending its last week in Baguio City and the Ilocos region to observe the Lenten Season. He seemed to have gotten hold of himself.

In his interview with Joaquin, he portrayed himself as the calm, cool, and collected commander-in-chief, giving instructions on the telephone to palace guards while eating his supper at the height of the January 30, 1970 siege of Malacañang.

Maybe to keep this composure, he fortified the palace to fend off any military incursion. “All the windows of the Palace facing Aviles,” observed Joaquin, “have been paneled up with plywood.” There was a sepulchral quality to the place. “In the hall of the chandeliers, lights burn before the Santo Niño enshrined on an altar.”

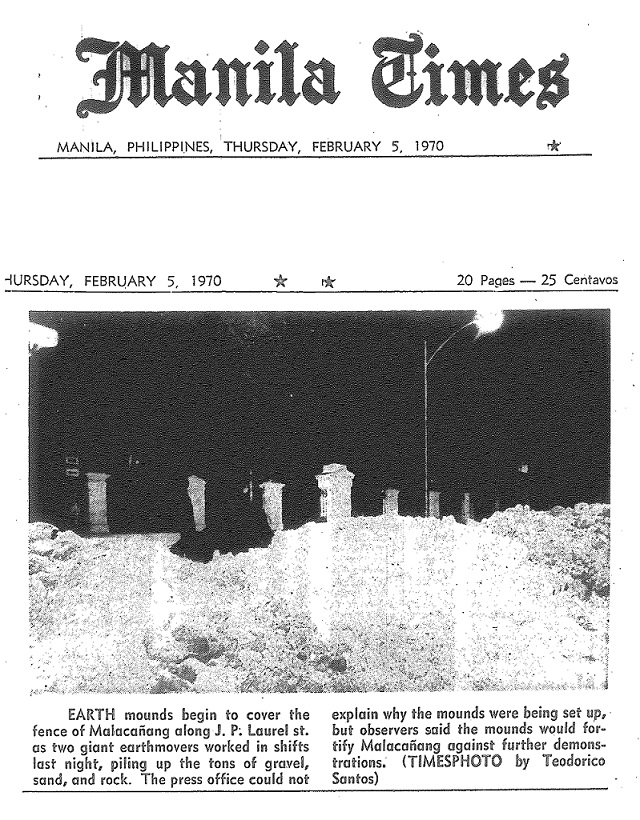

On February 5, 1970, the Manila Times published a photograph of earth mounds being piled up along the fences of Malacañang. Joaquin asked him about it. Marcos showed him pictures, claiming the diggings “were for power-line pipes. Since the rioters had cut all the wires along the fence . . . there has been no putting up of unusual constructions for the defense of the Palace.”

Manila Times photo, February 5, 1970

This was belied by his press secretary, Kit Tatad, who recalled seeing: “a machine-gun nest.” Tatad made the disclosure to William C. Rempel in Delusions of a Dictator. What Marcos denied, Rempel debunked:

Emergency remodeling projects were launched throughout the palace. The president’s basement gymnasium was converted into a bunker, a fully stocked shelter with baffled walls to withstand mortar attacks. Outside, armored gun emplacements were constructed at the gates. The lawn west of the veranda was cleared and lights were installed, making it a helicopter landing zone. Overnight, new fences went up. Instant foxholes pockmarked the lush grounds.

For security reasons, it was understandable that Marcos downplayed the fortification of Malacañang. The changes, however, offered a clear view to the bunker mentality that had set in on his mind. His February 28, 1970 diary entry said the “cement shelter in the ground floor [of Malacañang] has just been finished,” and that it was built to withstand “any possible mortar or grenade attack.”

Arturo Aruiza, one of Marcos’s closest aides, said in his book Ferdinand Marcos: Malacañang to Makiki that on the night of the Battle of Mendiola, he led a convoy of trucks from Malacañang “loaded with papers, guns, ammunition, and money” to Baguio, where he set up a contingency seat of government. Aruiza said Col. Fabian Ver summoned him back to Manila weeks later.

Even the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency saw through Marcos’ attempts to project himself as a fearless leader. In an intelligence memorandum titled “Philippine Student Agitation,” dated April 3, 1970, the CIA noted that “Marcos’ fearful concern for his personal safety, reinforced by the influence of soothsayers who have predicted his assassination, have caused him virtually to barricade himself in the presidential palace.”

However, the ghosts of those who died in the January 30, 1970 Battle of Mendiola cannot be kept at bay by the new fortifications in Malacañang. Marcos had to devise a political ploy to give his administration a facade of compassion for atrocities he himself was partly responsible for. (To be continued. Part II: Of Pillboxes and Firearms)

(Miguel Paolo P. Reyes and Joel F. Ariate Jr. are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Larah Vinda Del Mundo, Judith Camille E. Rosette, and Mary Ann Joy Quirapas provided research assistance. This piece is part of their on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research.)