On a stormy day in the 1990s, Carolyn Dagani and a co-worker were heading home after classes were suspended at the private school they worked in. The only Deaf persons at their workplace, they soon found out that the heavy rains, floods and lack of public transport were far from their only struggles that day.

Dagani and her colleague managed to get on a jeepney after a four-kilometre trek through dirty floodwaters that started from the city hall of Manila, which was near their school. “The two of us ran [to the jeepney] and almost fell,” Dagani recalled, using Filipino Sign Language (FSL) through an interpreter. But after boarding the jeepney, “we didn’t know how to communicate, especially when we wanted to pay. It was so awkward,” she added.

Arriving in Cubao, a district in Quezon City, the cold and hungry pair then waited till the rain eased at midnight. so they could continue their journeys home. By this time, they were not only literally stranded in the dark. They were left in the dark too, unable to get updates and public announcements about the storm.

“It was really challenging, because I couldn’t hear the news. I didn’t know what was going on,” added Dagani, who is project lead for inclusion of Project SIGND (Signs for Inclusive Governance and Development), an initiative to update and strengthen how climate change is communicated through FSL.

While there are more ways for the Deaf to access news and information today, the communication barriers that Dagani and her colleague faced three decades ago remain. These persist at a time when a warming planet is causing extreme weather events, such as typhoons, to get stronger and cause more destruction – but basic public information about disasters do not reach the Deaf community effectively. Many among them also lack knowledge about the climate crisis.

A country of 114.4 million people, the Philippines ranks high in lists of countries most vulnerable to disasters, including climate-related ones. It had the highest overall disaster risk, calculated from exposure and vulnerability, among 193 countries in the World Risk Index 2024.

“Like many other marginalised sectors, the Deaf have not been given the attention they deserve [during climate emergencies], precisely because they are marginal,” said Perpi Tiongson, co-lead for adaptation of Project SIGND, which is an initiative of the non-profit Oscar M Lopez Centre. “Despite the mantra to ‘leave no one behind’, the general approach still tends to be utilitarian, where the good of the many outweighs the good of the few.”

In climate- and weather-related emergencies, members of the Deaf community often do not receive enough critical safety information such as evacuation orders, and lack access to health facilities and mental health support. Deaf Filipinos rely heavily on social media, including Facebook Live and video tools, to get information and access their networks, or ask for help. Many build and use their own networks or ask neighbours and friends to translate government alerts.

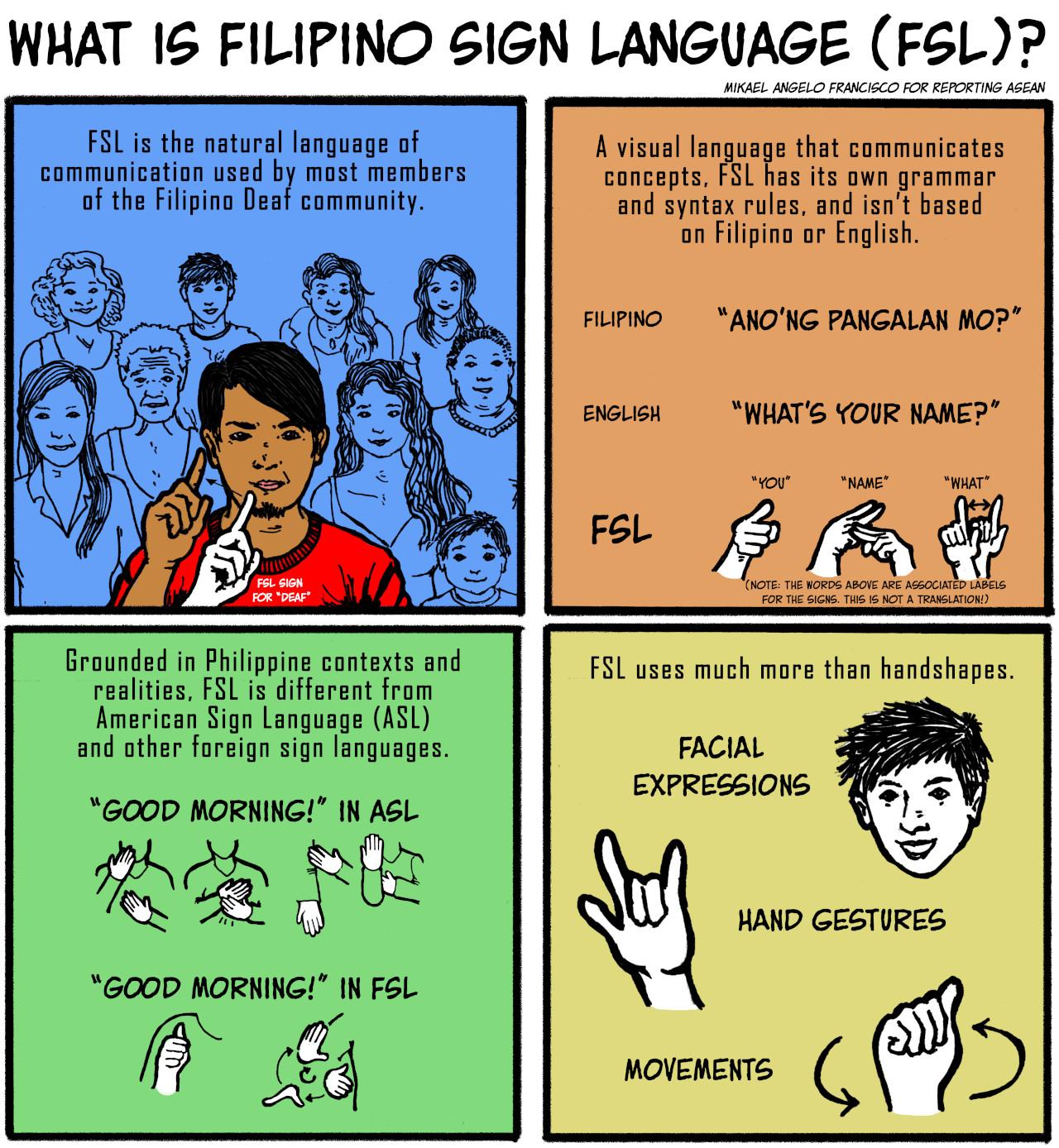

A DIFFERENT LANGUAGE

Alerts on weather and other disasters are sent out in the form of SMS advisories from government agencies and social media posts from local government units. But these are difficult for the Deaf to fully grasp, since they use a different language. They usually use FSL, which is a concept-oriented visual language that uses hand signs, facial expressions and gestures and is not patterned after English and Filipino words and grammar.

The government’s early warning systems have been “generally inaccessible to the Deaf community as they are primarily in national spoken or written language and often audio-based”, said ‘The Climate Realities of the Deaf’, a policy brief based on a climate vulnerability assessment of the Filipino Deaf community. Local governments usually use sirens to signal high water levels, it added.

The text alerts on weather and warnings sent out by the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council, which provides information on disaster preparedness, are in Filipino. This works for the general public – but the national language is not commonly used or understood by the Filipino Deaf, says a Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment (CCVA) Report on the Deaf Communities in the Philippines.

Most in the local Deaf Community use both FSL and English (38%), followed by 12% who use FSL only and 10.5% who use English only, the same report said. This is so because Deaf persons who went to school learn and use English and FSL, but there are others who did not learn FSL. There are 1.78 million Filipinos aged five or older who have difficulty of hearing, going by the Philippines’ 2020 population census.

Many Deaf persons rely on sign-language interpreters on television news shows for weather updates, but these come with their own challenges. For instance, these forecasts typically air in the late afternoon but would be much more useful in the morning, before people leave home. Closed captions on television or Facebook and other social media help some Deaf persons understand content better.

“We’re left behind in terms of weather news,” Project SIGND team member Jennifer Balan, a member of the Deaf community, shared through her interpreter.

For updates on the weather and calamities, 77% of the Filipino Deaf community rely on Facebook, followed by 66% who rely on text alerts from the national disaster council and 24%, from local governments, the same CCVA report says.

It was through a Facebook post by the Philippines’ weather agency that Balan became aware of Super Typhoon Yagi (locally called Enteng), which roared through the country in September before bringing massive floods across parts of Southeast Asia. But she had to ask someone to explain important details, such as where the typhoon would hit, because the text-based warning was hard for her to understand.

“Real-time updates are usually only through text messages,” lamented Balan, “so we end up getting shocked when there are already reports of [weather-related] casualties and damages.”

In an August update, researchers with the Lopez centre, which works on climate resilience, recounted stories that show the greater, and different, ways that persons with disabilities are more vulnerable to climate hazards like floods, droughts, storms.

One researcher found a Deaf mother who, unaware of howling winds and heavy rains from Super Typhoon Yolanda (known internationally as Haiyan, one of the most powerful tropical cyclones recorded) in 2013, was only able to prepare her family for evacuation at the last minute – after someone gestured the situation to her. After Super Typhoon Odette (international name Rai) struck in 2021, a Deaf senior citizen told another researcher that he could not understand the instructions being given by people distributing relief goods.

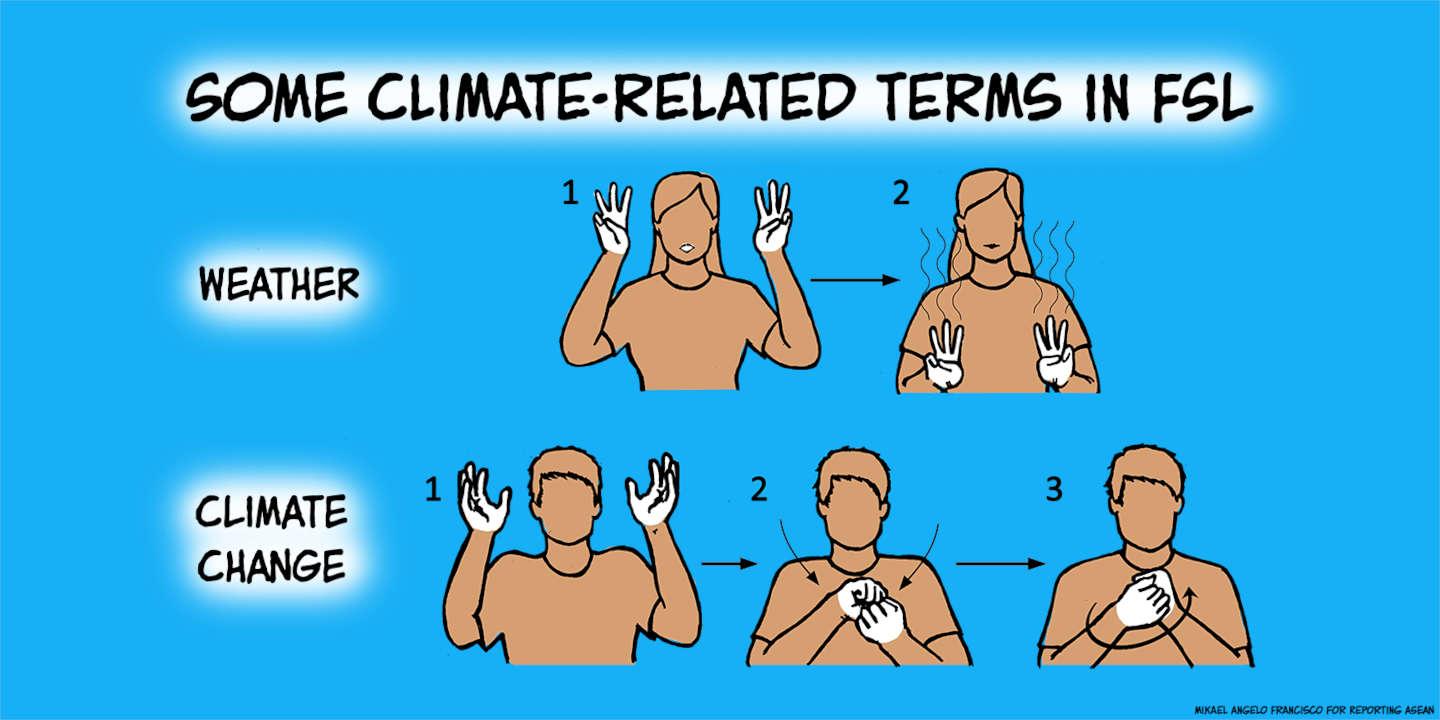

But it is not just the modes of information delivery that cause the Filipino Deaf to be left behind in the climate discussion. Climate change may be all over the news, but this does not translate into information accessible for the Deaf. Climate science is full of technical concepts that have no direct FSL counterparts, making it difficult to discuss climate issues in FSL.

Dagani cites the compound word ‘greenhouse’ as an example: “If a person signs ‘greenhouse,’ they might use the signs for ‘green’ and ‘house,’ but [Deaf persons] might not understand the concept. They might just think about a green [coloured] house, even though the real concept is a layer of gases surrounding the Earth.”

‘Greenhouse gas’ is, in fact, among the 42 new climate-related FSL concepts that will be released in 2025 by Project SIGND, which has been identifying climate-related FSL signs in use and developing them into a corpus, or a documented record of language, for the Deaf community as well as translators.

FSL users can use the standardised and added climate concepts in discussions and learning, similar to how other sign languages have been updated with climate content. (In 2023, 200 new signs, many of them related to climate science, were added to the British Sign Language ‘science glossary’.)

SPEAKING CLIMATE IN THE FILIPINO SIGN LANGUAGE

Over two years and with the use of descriptive pictures and video recordings, the Project SIGND team gathered more than 6,000 climate change-related signs that are being used in the Filipino Deaf community. This was narrowed down to 1,039 signs that can represent 26 significant climate-related concepts. For concepts with no existing FSL signs such as ‘carbon footprint’ and ‘seawall’, the team worked with climate scientists and linguists to develop 42 new signs.

Both existing and new signs were reviewed by a panel of 10 Deaf community leaders, who evaluated them based on adherence to FSL structure and signing rules, clarity, visual representation, accuracy and uniqueness.

“The Deaf FSL researchers on the team were just as surprised to discover how rich the existing vocabulary is, with many regional variants thriving,” said Tiongson. Clarifying that the project’s primary aim was to document the climate-related signs that were already in use, she said: “Only when really necessary did the project create new signs, which need to be tested to see if the community will eventually pick it up.”

“Just like spoken languages, vocabulary is not just created and prescribed; it must be used, otherwise it will not take up,” she explained. “Language does not work this way, and the Deaf are particularly mindful of this process.”

CLIMATE SCIENCE IN THE DEAF CURRICULUM

The Deaf are generally not that familiar with climate change, Balan explains. “Most [Deaf persons], as high school students, were not taught these concepts, so they don’t have any background,” shared Balan, who manages vocabulary development, collecting data and coordinating with Deaf persons across the country in Project SIGND.

She added that many adults, particularly those in their 50s or 60s, “don’t know much about FSL,” likely due to the fact that the Deaf’s access to education is a challenge in itself.

Science-related signs [taught in schools attended by Deaf students] are typically limited to basic concepts like the human anatomy, and “very few” are climate-related, according to Balan. Some of the Deaf persons Balan’s team spoke to had trouble differentiating related weather concepts like ‘rain’, ‘heavy rain’, ‘light rain’, ‘typhoon’ and ‘storm’. “Just like in hearing people, some [Deaf persons] recognize the words, but are not familiar with their meanings,” she explained.

As a visual language, FSL partly relies on facial expressions to help signers express and distinguish intensities. A concept like ‘heat’ is signed with a “more neutral” face, while superlative or intense descriptions like ‘extreme heat’ come with more expressive facial gestures, Balan explained.

Currently, FSL signers rely on finger-spelling to communicate technical climate words, as well as visuals to establish context. Perhaps unsurprisingly, learners end up constantly asking for confirmation or asking their teachers to repeat their explanation.

Balan recommends incorporating climate-related FSL concepts and signs into education early on: “Children understand climate-related FSL concepts better than other age categories. Hopefully, they learn about this as a subject… I know that they have the knowledge to learn, the capacity to learn, but it’s not being taught to them.”

OF CLIMATE SIGNS AND SIGNS OF CHANGE

Dagani and Balan said they barely knew anything about climate change before joining Project SIGND.

“One of the project scientists gave us an overview of climate change, and to be honest, I was overwhelmed because all of this was new knowledge,” said Balan. “I became more familiar with the greenhouse effect, carbon emissions, carbon dioxide, atmosphere.”

“Hearing people are more advanced [in their understanding of climate change] because they hear the news and [get to talk about it]. But Deaf people are being left behind,” she added.

In the project team’s discussions with the Deaf community, Balan noted: “They opened up all their concerns during our interviews, their emotions and complaints. Because the government isn’t helping and prioritizing them, they’re left behind and sort of oppressed… they felt that they were being excluded.”

“Now, there [is a corpus of] FSL signs related to climate change, so we are encouraging Deaf people and even hearing people to really learn them,” said Dagani.

“The Deaf can be so much more than mere victims of disasters,” Tiongson affirmed. “If given the opportunity for self-determination, they can be agents of change for their own transformation and resilience-building.”

—

This story follows the AP Stylebook guidance on the use of uppercase “Deaf” for people who identify with the community and culture, as well as in descriptions (e.g., Deaf inclusion, Deaf education). The lowercase “deaf” is used for describing the audiological condition of severe or complete loss of hearing.