A damaged F/B Gem-Ver lies at the shores of San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, Philippines. Photo from the Facebook page of Agriculture Secretary Manny Piñol.

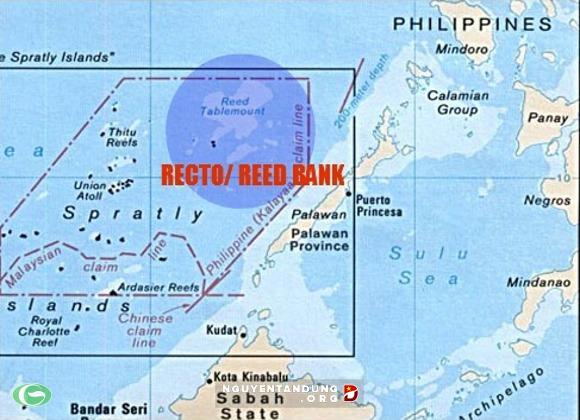

The sinking last week of Filipino-owned wooden fishing boat F/B GimVer 1 by a bigger Chinese ship in Recto Bank presents an expanding dynamic to Chinese expansionist claims over recognized Philippine maritime zones .

And Philippine dilly-dallying or worse, inaction, on the sinking incident risks inviting more of China’s cunning if dangerous game, which has been carried out for some time now by what American maritime security scholars call the Chinese “surging second sea force.”

President Rodrigo Roa Duterte may be right to say it is a bad idea to condemn without a proper investigation. But will he actually ask for such investigation on behalf of the 22 affected Filipino fishermen under the terms of the UNCLOS?

If a meeting with the Chinese Ambassador to Manila the Palace was reported to have called pushes through at all, one hopes the investigation is on top of the agenda for discussion.

The Recto Bank incident ostensibly falls under the same rules usually applied to the conduct of the “flag states” of ships in the high seas. But should the Philippines decide to seek recourse under these rules- found in article 94 of the UNCLOS – it would not be the first time that it would be doing so against Chinese “gray zone” tactics. Unfortunately, that first time it had done so appears to have been quickly forgotten under the Duterte administration.

Duties of Flag States

The EEZ being a zone outside the full sovereignty of a state, any maritime incident involving a ship or boat – criminal in nature or otherwise – is generally subject only to the jurisdiction of the flag state, or the country under which the vessel has been registered.

Thus, the UNCLOS imposes certain duties on flag states to ensure responsible navigation, as well as the protection of the maritime environment.Such duties, binding on both China and the Philippines, apply whether in high seas or in the EEZ.

“Each State shall cause an inquiry to be held by or before a suitably qualified person or persons into every marine casualty or incident of navigation on the high seas involving a ship flying its flag and causing loss of life or serious injury to nationals of another State or serious damage to ships or installations of another State or to the marine environment,” according to article 94. “The flag State and the other State shall cooperate in the conduct of any inquiry held by that other State into any such marine casualty or incident of navigation.”

Third-party investigation?

That it was a Chinese fishing boat that got entangled in the Recto Bank incident is not disputed by the Chinese embassy in Manila. However, it made the outrageous claim – despite evidence to the contrary – that the sinking was accidental, only that it was forced to flee the scene, leaving the Filipinos in the water, after the Chinese boat was allegedly besieged by a gaggle of Filipino fishing boats.

Given the brouhaha generated by the incident, it would be a good idea to refer the investigation to a competent and impartial third-party investigation. Article 94 allows this. Moreover, it imposes on the Philippines a duty to conduct, or refer it to, an investigation, and on China, a duty to cooperate with such investigation.

The auspices of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) may be tapped by both parties to facilitate a third-party investigation. The IMO is a UN specialized agency responsible for the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine and atmospheric pollution by ships. Or, the Philippines may go the route of the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea, like it did when it brought a landmark arbitral case against China in 2013.

Another option is to form a joint investigation body with China. The Duterte administration may even choose to do so only with the sole purpose of laying down agreed procedures between the two governments to prevent a similar incident from happening.

China’s Second Navy

Writing for the Spring 2019 issue of the US Naval College Review, American maritime security scholars Andrew S. Erickson Joshua Hickey, and Henry Holst charted a pioneering comprehensive study of China’s Surging Sea Force, or its now formidable “Second Navy.”

This refers to China’s maritime law enforcement fleet – now the world’s largest – that, as of 2017, counted 17,000 personnel, 225 ships of over five hundred tons capable of operating offshore, and two ten thousand-ton Zhaotou patrol ships, the largest in their class in the world. Many of its smaller ships, according to the scholars, were built with “reinforced ribbing along the hull” to survive collisions with – or ramming operations against – foreign fishing vessels.

Led by China’s People’s Armed People militia, with its own maritime fleet,the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM), this so-called ”Second Navy”,deployed to the South China Sea side-by-side and in close coordination with Chinese fishing vessels, provides a fearsome“gray zone” capability to Chinese maritime law enforcement efforts in the South China Sea, including in areas already recognized by international law as part of the Philippine EEZ.

Such capability is so called because, as the American scholars would put it, it allows Beijing to increase its influence over the maritime region without the direct use of People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) warships; in this way, China is able to project power while avoiding the risk of an armed conflict and allowing the Chinese Navy to focus on its primary mission.

Vietnam has so far borne the brunt of these ramming incidents involving the Chinese gray zone fleet, accordingly organizing its own maritime militia to protect its fishing fleets from the Chinese depredation.

The US Navy has taken note of this potent mix of China civilian and paramilitary capabilities, warning recently that it considers Chinese Coast Guard ships and fishing boats as no different from Chinese Navy ships. This came in the wake of a Pentagon report saying that the Chinese fishing fleet now routinely trains with the Chinese Navy and Coast guard to play“a major role in coercive activities to achieve China’s political goals without fighting.”

Duty to responsible navigation

In its 2013 arbitral case against China, under its 13th submission, the Philippines actually invoked the article 94 flag state rules for the first time. This involved the unsafe conduct of Chinese Navy and Coastguard ships and their cohort of fishing vessels towards the Filipino government vessels at Recto Bank, Scarborough Shoal and other areas within the Philippine Exclusive Economic Zone. It also brought to court the massive destruction in the South China Sea brought about by China’s construction of artificial islands on maritime features within the Philippine EEZ.

It is worth noting that a finding by the arbitral was that Chinese Navy and Coastguard ships had conducted themselves in “total disregard of good seamanship and neglect of any precaution.”

In its 500 plus-page 2016 ruling, the arbitral court said the Chinese conduct complained of violated the 1972 Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS), to which both countries are parties.

The 1972 COLREGS institutes sea traffic separation schemes, with rules on determining safe speed, the risk of collision and the conduct of vessels operating in or near sea traffic lanes. The rules apply “to all vessels upon the high seas and in all waters connected therewith navigable by seagoing vessels.”

More importantly, the arbitral court held that article 94 incorporates the COLREGS into the UNCLOS, and they are “consequently binding on China” It added that a violation of the COLREGS, as “generally accepted international regulations” concerning measures necessary to ensure maritime safety, “constitutes a violation of the Convention itself.”

It added that the international regulations on safe navigation at sea is a concern independent of the question of entitlements to the maritime zones in dispute.

If the Philippines were to downplay what happened to F/B GimVer 1 as a “simple maritime incident” that has been blown out of proportion, it would be a virtual surrender of a key victory already won by the Philippines in its arbitral case against China.

Worse, it would mean altogether leaving the fate of struggling Filipino fishermen to the cruel mercies of China’s surging second sea force.

Romel Regalado Bagares, an alumnus of the UP College of Law, lectures in public international law at the Lyceum Philippines University College of Law and is secretary of the Philippine Society of International Law. The opinion expressed in this essay is entirely his and does not reflect those of his aforementioned organizations.