(This article was first posted on GMA News Online)

You’re driving along, minding your own business, and

obeying the rules of the road. Suddenly, a police officer signals you

to pull over. You stop. He tells you that he wants to give you a breath

test to measure the amount of alcohol in your system.

Do you cry “invasion of privacy”? You could, if you were driving in

the Philippines. Here, a law enforcer cannot just stop any driver to

give a breath test for alcohol.

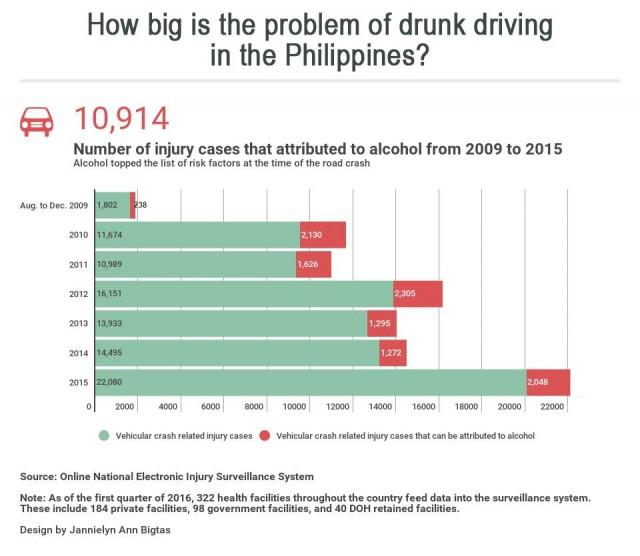

It’s a long story: The Philippines does have a drink driving law in Republic Act (RA) 10586. It is known as the “Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act of 2013.”

RA 10586 states that the law enforcer first needs to have “probable

cause” to believe that the driver has had too much to drink. This means

that he first needs to witness a traffic violation—such as lane

straddling or speeding.

Only then can the law enforcer flag down a driver. At first, he

conducts 3 field sobriety tests. If the driver fail any of the tests,

then the law enforcer can use a breathalyzer to determine his blood

alcohol concentration level.

Random breath testing to detect alcohol

is a highly visible exercise. Such tests could be encountered anywhere

and at any time in the land Down Under. Photo: WHO/Passmore

In the land Down Under, though, it’s an entirely different story.

Australian law allows for random breath testing (RBT). This means that

the police can stop any driver at any time for breath testing. The

driver need not behave in a way that suggests he is drunk.

“RBT is conducted by police in static, highly visible checkpoints or

by mobile police on normal patrol duties,” write researchers Kiptoo

Terer and Rick Brown in

their paper. “Drivers are determined to be impaired if their blood alcohol concentration (BAC) exceeds a legally prescribed amount.”

Legal advice

Can someone refuse a random breath test in Australia? FindLaw Australia strongly advises against it.

Refusing to take a breath test is treated as a serious offense, says

the FindLaw team. In Queensland for example, anyone who refuses to take a

breathalyzer test faces a fine of A$4,000—a whopping ?147,700—or six

months in prison. In addition, “anyone who gives an unsatisfactory

sample, such as trying to blow a little lighter so there may be no

reading, will be judged to have refused a breath test and is guilty of

an offense.”

And think again before attempting to do the old switcheroo with

someone who had been drinking and driving: “The police can also request a

breath test from a passenger of a vehicle who they reasonably believe

was a driver.”

“RBT is a leading drink driving countermeasure implemented throughout

Australia,” say Terer and Brown. The country’s experience with RBT

since the 1980s shows that it saves lives.

- In New South Wales, the introduction of RBT in 1982 initially

reduced fatal crashes by 48% over a period of four and a half months.

Subsequently, RBT lessened fatal crashes by an average 15% over a

10-year period. - RBT led to a reduction in fatal crashes of 35% in Queensland and 28% in Western Australia over a four-year period.

- Static, highly visible RBT checkpoints in Victoria in 1990 led to a

19% net decrease in fatal crashes during peak hours of alcohol

consumption.

Elsewhere, RBT has also had positive outcomes, say the Australian researchers.

- In Finland, RBT led to a 58% decrease in drink driving between 1979 and 1985.

- In New Zealand, the introduction of RBT in 1993 led to a reduction

in fatal and serious crashes of 38% in rural areas and 35% in urban

areas during high alcohol hours. - In Ireland, the introduction of RBT led to a 19% decrease in road fatalities in 2006.

RBT is a cost-effective road safety measure, too.

- A 2004 study in New Zealand found

the cost-benefit ratio was 1:14.4 for RBT alone, 1:18.8 for RBT coupled

with a media campaign, and 1:26.1 for RBT with both a media campaign

and “booze buses.” These are “large, specially equipped vehicles used

for evidentiary breath testing, which are typically very distinctive in

order to attract the attention of nearby road users.” - A 2004 report by the World Health Organization stated that each dollar spent on RBT results in a cost saving of $19.

- In New South Wales, Australia, the estimated cost-benefit ratio of random breath testing ranged from 1:1 to 1:56.

Have your say!

Despite RA 10586, the dearth of breathalyzers in the Philippines has

tied the hands of law enforcers. There are only 150 breathalyzers in the

entire archipelago. There are simply too few of the gadgets to test

enough drivers and to deter them from drunk driving.

Let’s imagine for a moment, though, that there are enough

breathalyzers in the country. Would drivers be in favor of introducing

random breath testing?

Motoring journalist James Deakin is all for it. “If we were serious

about RA 10586, they could introduce the random breath testing vans… at

key exits of the city or night spot areas or even car parks,” he says in

an email interview. “Have these professionally manned and with CCTV so

there’s no foul play.”

But what about those who will cry “invasion of privacy”? Deakin

believes random breath testing is “less invasive than any airport or

mall security check we go through.” So please, he appeals, “let’s not

sweat the petty stuff.”

Dinna Louise C. Dayao (dinnadayao@gmail.com) is an independent

writer-editor. In September, she attended Safety 2016, a major injury

prevention conference in Finland, with support from the ICFJ-WHO Safety

2016 Reporting Fellowship Program and Bloomberg Philanthropies.