By ELLEN T. TORDESILLAS

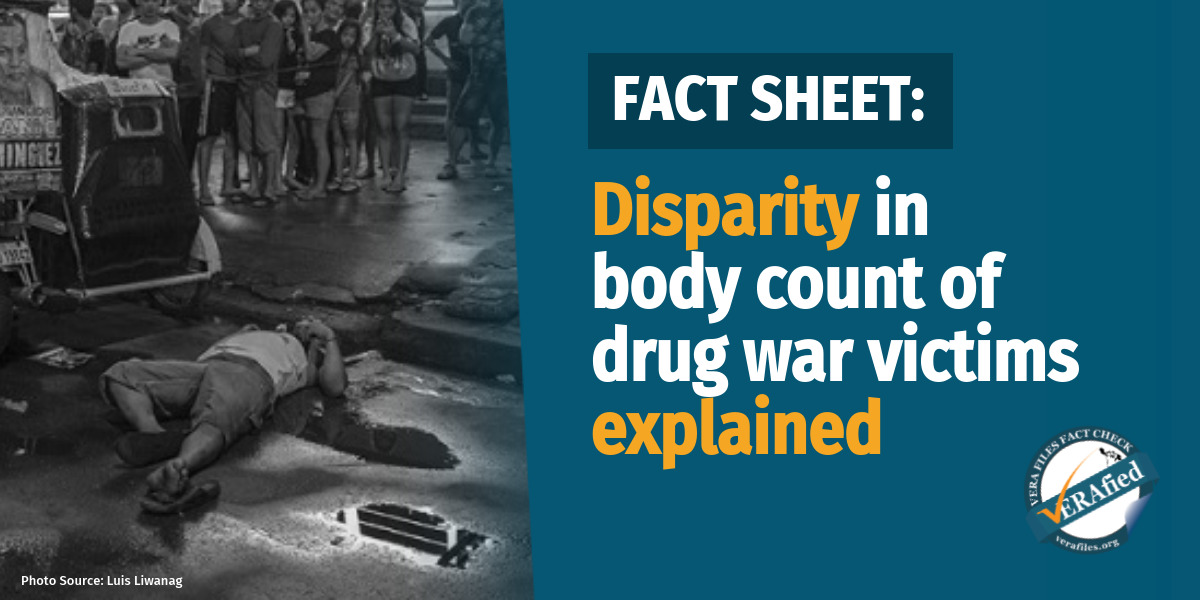

DO you feel sick watching daily images on TV and newspapers of people killed, lying lifeless on the sidewalks covered with newspapers or plastic with only their dirty feet and worn-out rubber slippers seen?

And of course near the corpse, the cardboard sign “Drug pusher ako, huwag tularan”, which has now become a standard accessory in President Duterte’s war against illegal drugs.

Studies have shown the ill-effects of being exposed to traumatic images.

In an article in the website of Association for Psychological Science, psychological scientist Roxane Cohen Silver of the University of California, Irvine and colleagues said “repeated exposure to vivid traumatic images from the media could lead to long-lasting negative consequences, not just for mental health but also for physical health. “

The article said Silver and her colleagues “speculated that such media exposure could result in a stress response that triggers various physiologic processes associated with increased health problems over time.”

That’s for those who are exposed to disturbing images in media. How much more with members of media who are up close to those gruesome scenes to capture them for the people to know what’s happening in the country.

Raffy Lerma, the Philippine Daily Inquirer photo-journalist, who took that heart-wrenching “La Pieta” photo of Jennelyn Olaires cradling the dead body of her pedicab driver partner, Michael Siaron, was quoted in an article written by Pocholo Concepcion, that he is getting overwhelmed by the rising body count as the killings intensify in Duterte’s war against illegal drugs.

“Hindi bumababa sa lima ang patay bawat araw, minsan 10, may araw na 18. If I will add everything for that week, it would be more than the total for the year when I first did the nightshift in 2005,” he said.

Lerma related the anguish that he and his fellow photographers also go in covering the Duterte administration’s drug war.

He said when he went to Pasay City Rotonda in the early hours of July 22, it was the third death for that night that he had to cover.

Lerma said Olaires was pleading for help as he and the photographers were taking pictures but they couldn’t do anything. The area had been cordoned by the police.

After that, they went to Leveriza st, also in Pasay, which is now being grimly referred to as “Patay City.”Another killing. But the body of the victim – said to be a person with speech disability- had already been removed from the crime scene.

Lerma related, “We were quiet as we went back to the Manila Police District, the office of graveyard-shift media workers. I lighted a cigarette to calm my nerves. Another photographer took deep breaths. Together, we recounted moments from the scene at Pasay Rotunda.

“Another veteran photographer said, while shaking his head, ‘’ no longer want to be a photographer.” We all had the same feeling of guilt.”

In the end, Lerma said, they consoled themselves that it’s part of the job.

“We may not have helped the victim and his partner but it is our job to show these pictures. We have to show reality as it is and perhaps, get people to react and even take action,” he said.

Dr. Elana Newman, a licensed clinical psychologist who conducted a survey of 800 photojournalists, in an article at the Dart Centre website, said, “Witnessing death and injury takes its toll, a toll that increases with exposure. The more such assignments photojournalists undertake, the more likely they are to experience psychological consequences.”

Dart Centre Europe, a regional hub for journalists and filmmakers who believe that effective reporting on violence and trauma matters, has a 40-page guide by Joe Hight and Frank Smyth to help journalists, photojournalists and editors report on violence while protecting both victims and themselves.

For the journalists, here are some advice:

- Know your limits. If you’ve been given a troublesome assignment that you feel you cannot perform, politely express your concerns to your supervisor. Tell the supervisor that you may not be the best person for the assignment. Explain why.

- Take breaks. A few minutes or a few hours away from the situation may help relieve your stress.

- Find someone who is a sensitive listener. It can be an editor or a peer, but you must trust that the listener will not pass judgment on you. Perhaps it is someone who has faced a similar experience.

- Learn how to deal with your stress. Find a hobby, exercise, attend a house of worship or, most important, spend time with your family, a significant other or friends – or all four. Try deep-breathing.

- Understand that your problems may become overwhelming. Before he died in April 1945, war correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote, “I’ve been immersed in it too long. My spirit is wobbly and my mind is confused. The hurt has become too great.” If this happens to you, seek counseling from a professional.