[metaslider id=34942]

Text and photos by ALANAH TORRALBA

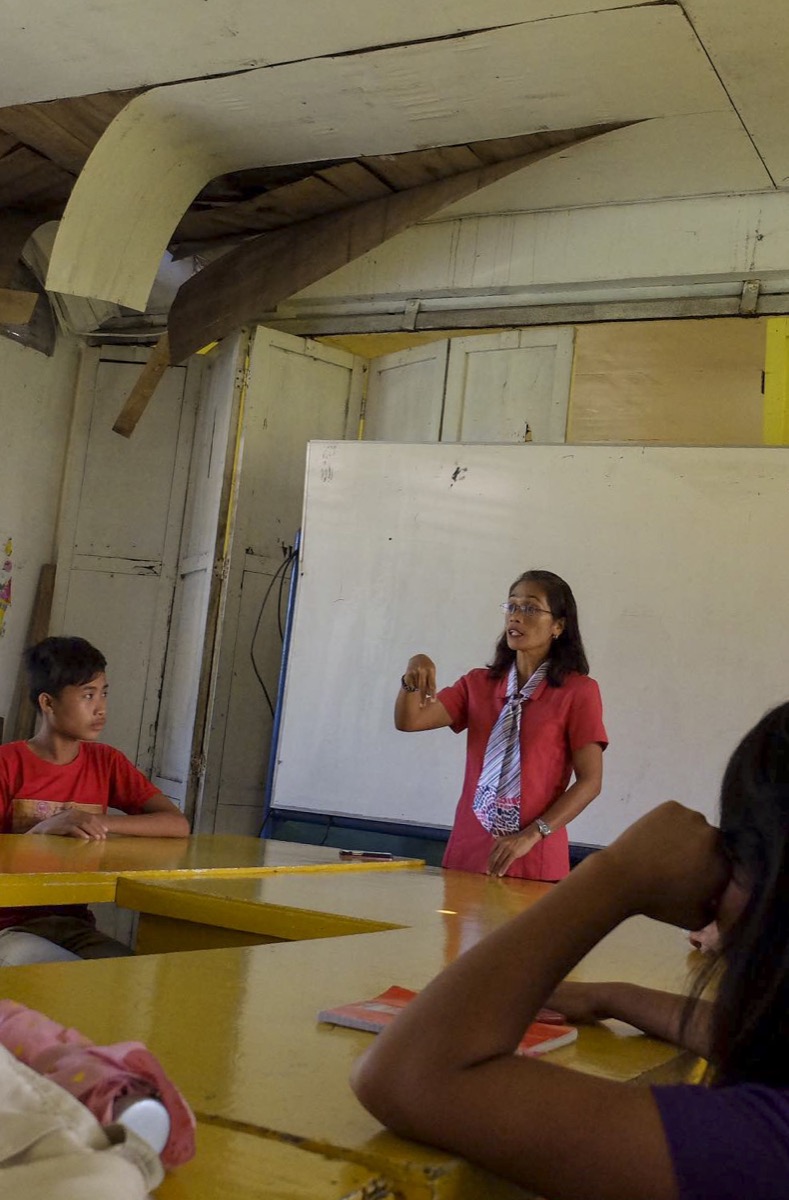

CATARMAN, Northern Samar — Classes are held in rooms without roofs, and when it rains, the rooms are swamped with floodwater.

This lone Special Education Center (SPED) in Northern Samar sustained heavy damage from Typhoon Nona (International Name: Melor) last year. Some 1,200 classrooms were destroyed, costing an estimated P689 million.

Located in the capital Catarman, which is frequently on the path of typhoons, this school for students with disabilities struggles to make do with improvised fixes.

One teacher says she usually has to cancel classes the day after when it rains, because mosquitoes are quick to infest the classroom.

The regional Department of Education (DepEd) has just recently started repairs on the roof. A damaged room is worrying, as the risks are far worse for students with disabilities.

Mildred Horca, a SPED teacher for 15 years, says her deaf students would not be able to notice the signs of a collapsing ceiling until it is too late.

Typhoon Nona also destroyed SPED workbooks and other learning materials, forcing teachers to get creative.

FrizianneBaylon, 27, a teacher for three years, says she and her co-teachers are forced to photocopy these materials since they cannot afford to buy one workbook for each student.

She says they have never received donations of books for SPED students.

Deep-rooted challenges like these continue to hound SPED teachers in the province, which ranks among the poorest in the country.

Mildred Horca teaches her class of deaf students at the Catarman SPED Center in Catarman, Northern Samar.

While aid from both government and foreign organizations have been pouring in for public school students, Josephine Cornico, the principal of the SPED Center, says the needs of children with disabilities seem to have been neglected.

The lack of training for teachers also remains a challenge.

Erlinda Aniban, a SPED teacher for 18 years, says that while the DepEd provides yearly seminars, not every SPED teacher is accommodated into the trainings.

At present, DepEd identifies only a handful of teachers from around the country to attend these.

“Sometimes, even non-SPED teachers get the training while those of us who do teach in SPED, do not even get chosen,” she says.

The SPED center in Catarman has four teachers, but only one has a Master’s degree in Special Education.

Frequent trainings would go a long way not just for the capital, but also for the rest of the province.

Pushing for inclusive education

To meet the needs of children with disabilities in places like Catarman, at least nine bills were filed during the 16th Congress to create a special education law.

House Bill 4558, a consolidation of SPED bills, aims to establish and provide funds for centers in all public school divisions.

A provision of the bill also requires that in addition to teachers, each SPED center should have a program director and an administrative committee composed of physical, occupational and speech therapists, as well as a developmental pediatrician or educational psychologist.

But this bill only made it as far as transmission to the Senate.

Had the bill been enacted into law, SPED centers, especially those in far-flung areas, could administer their admission process more accurately.

Aniban says the process of admitting students into the SPED program is a simple assessment and interview with the parents, which she admits can be unreliable without the presence of a child psychiatrist.

Potential students are made to take a written test to assess their learning proficiency while those who cannot write or read are diagnosed through their parents’ interviews.

Aniban says she hopes a child psychiatrist could visit the school so that students could be correctly diagnosed of their disabilities.

A child psychiatrist could also help children with disabilities cope with the devastation wrought by a calamity, like Typhoon Nona.

While all students share the same problems after a typhoon — such as lack of shelter, food and, clothing, natural disasters — such devastation can be especially difficult for children with disabilities.

Principal Cornico hopes that in the future, the SPED program can integrate lessons on how to cope with natural disasters into the curriculum. She says lessons on natural disasters are already included in Science classes but admits more need to be done.

“Whenever there are programs for the normal children, our [SPED] children are forgotten,” she says.