All that officials who are being paid by Filipino to manage the country can say about last Monday’s disastrous General Community Quarantine, when thousands were left stranded waiting for public transport that never came was “konting pasensiya.”

“On the first day of the GCQ, humihingi ako ng pasensya. Forgive us if it creates inconvenience, “Transportation Secretary Arthur Tugade said on CNN Philippines.

Ïf it creates inconvenience? Big time!

Patience? The gall to put the burden on the suffering commuters.

Instagramer Musthavednissaid, “Matagal na pong naubos ang pasensiya. Mas naunang naubos (kaysa) sa face mask. (I have long ran out of patience. Much ahead of the face mask.)

One clerkwho desperately needed to work to earn for the family, had to wake up at2 a.m. and walked for four hours from Fairview to Edsa MRT hoping to get a ride to Makati only to find a long line of people like him, tired and running out of patience.

He was not sure what time he would be able to reach his office. And how about going home in the afternoon? Will it be the same tomorrow? Will this be the new normal?

The incompetence is unforgivable. Government has the data on the number of people who use public transport every day. Officials knew that public transport that were allowed to operate had a severely reduced capacity due to the physical distancing requirement.It takes only simple math and common sense to know that there would be a shortage of public transport.

But then. one has to have genuine concern for commuters to think of alternative solution, to field more public transport. That is what officials do not have.

***

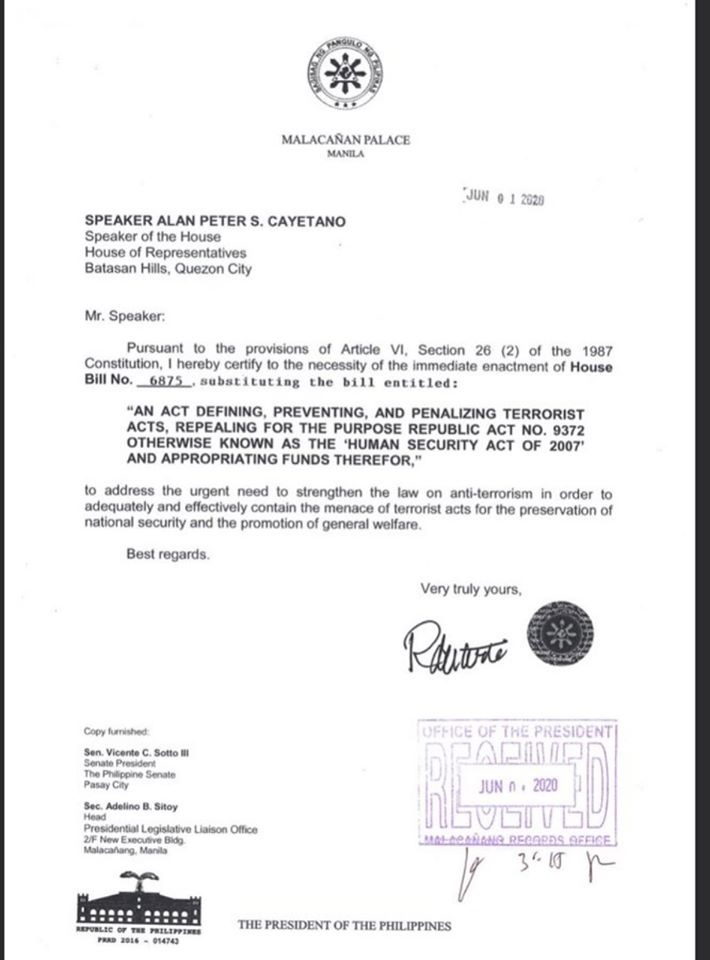

While officials were running clueless how to deal with Covid-19- related

problems that their incompetence helped create, President Duterte was

more interested about another monster-in-the making. On Monday, he

certified as “ürgent” House Bill No. 6875 after the House Committees on

Public Order and Safety and on Defense and Security agreed to adopt the

Senate version of the bill that would amend the Human Security Act of

2007.

Human rights advocates have expressed opposition to the bill. The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines said, “This bill which is much worse than the repulsive Human Security Act of 2007, would negate so many of our rights, including those to freedom of the press and of expression, and institutionalize impunity with the removal of justifiably harsh penalties against abusive implementors of the law.”

Last March, VERA Files did a short fact sheet on the Senate version of the bill and highlighted three elements that differed it from the HSA:

1. The bill expands the definition of terrorist acts.

The HSA, enacted in 2007, defines terrorism as the violation of certain provisions of the Revised Penal Code — such as piracy, rebellion, insurrection, coup d’ état, murder, kidnapping and serious illegal detention — for the purpose of sowing “widespread and extraordinary fear and panic” in the people in order to “coerce the government to give in to an unlawful demand.”

Under the Anti-Terrorism bill, on the other hand, terrorism is committed when persons within or outside the country engage in certain acts, “regardless of the stage of execution,” for the purpose of intimidating the whole, or a segment of the general public and creating an “atmosphere of fear” to:

-provoke or influence [through] intimidation the government or any of its international organizations;

-seriously destabilize or destroy the fundamental political, economic, or social structures of the country;

-create a public emergency; or,

-seriously undermine public safety.

2. The bill extends the amount of time a suspected terrorist can be detained after a warrantless arrest and removes the P500,000 fine for erring officials.

Under the HSA, a person arrested without a warrant for terrorism may be detained for a maximum of three days, and must be presented, prior to detention, to the nearest judge, who will determine whether or not the suspect had been subjected to any physical, moral, or psychological torture, among other tasks.

Failure to release the person on time or present them to the judge will result in a penalty of imprisonment for 10 to 12 years.

Sec. 29 of the proposed law, on the other hand, seeks to extend the days of detention to 14, with an option to extend for another 10 days, if necessary, to preserve evidence, prevent an upcoming terrorist attack, or properly conclude an investigation.

It did not include the provision requiring law enforcers to present the suspected terrorist to the nearest judge prior to detention. Keeping the person for more than 14 days without the conditions for extension has a penalty of 10 years imprisonment.

Both measures provide for the rights of the detained, including a logbook on the procedures and visitors of the detained, their right to legal counsel, their right to privacy, and their visitation rights.

The bill, however, drops the provision on damages for unproven charge of terrorism under Sec. 50 of the HSA, which entitles any person wrongfully accused of terrorism to P500,000 for every day spent in detention. Sen. Panfilo Lacson, the sponsor of the bill, said this provision made law enforcers hesitant to file charges based on the HSA for fear of paying fines.

3. The bill extends the period of time a person’s communications can be put under surveillance.

The HSA currently allows up to 30 days of surveillance of a suspect’s phone communications, provided there is probable cause and the law enforcer or military personnel gets permission from the Court of Appeals. The wiretap period can be extended or renewed for another period not exceeding 30 days if the case is in the public interest and the original applicant for the permission files for it.

Sec. 16 of the anti-terrorism bill, on the other hand, expanded the original 30-day period to 60 days, but maintains the period and requirements for an extension.

In both cases, communications between lawyers and clients, doctors and patients, journalists and sources, and confidential business correspondence are not allowed to be recorded.

The views in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.