Did the government investigate former president Rodrigo Duterte, Sen. Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa and other high-ranking officials for their roles in the drug war that resulted in the deaths of thousands of drug suspects? Have they been cleared?

It seems these are crucial questions that the International Criminal Court (ICC) has been waiting for the Philippine government to answer instead of blocking the Netherlands-based tribunal from investigating the killings.

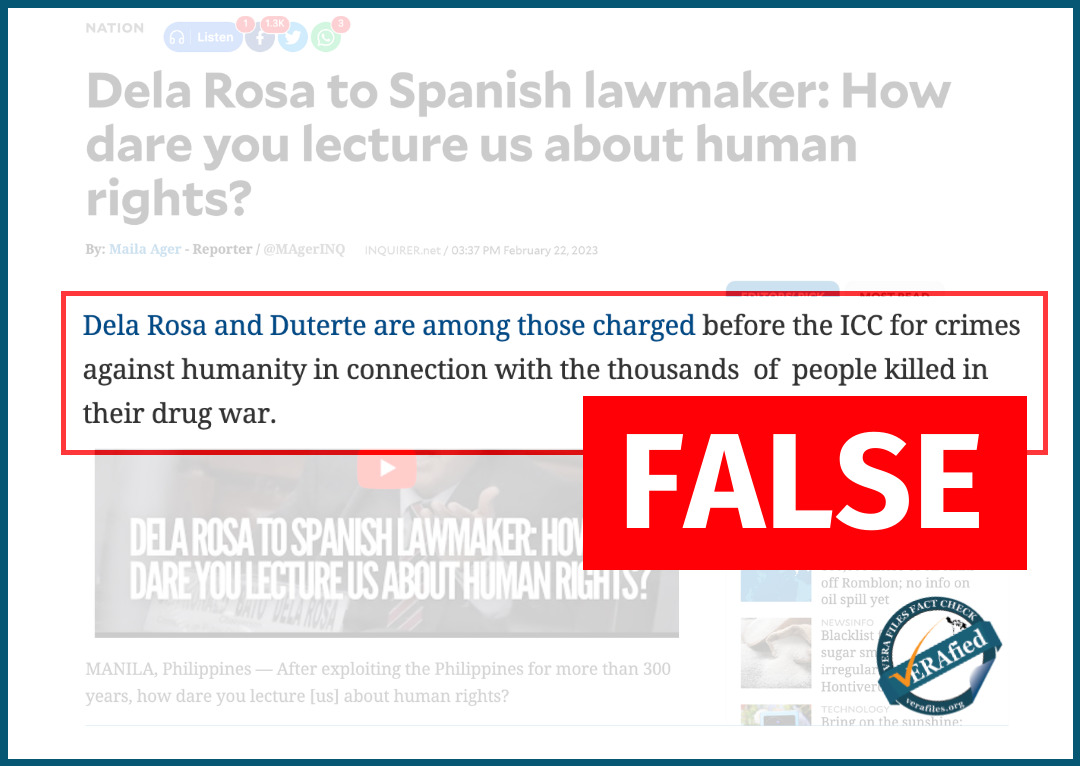

Officials of the previous and present administrations have been singing the same tune against the ICC, harping on the probe as an “intrusion” into the country’s internal affairs and a “threat” to its sovereignty while claiming that the Philippines has a functioning and independent judicial system.

Apparently, they want to create the illusion of truth, that a lie repeated often enough becomes the truth or perceived by many as the truth.

They skip the fact that Philippine authorities had sufficient time to dig deep into the deaths of at least 5,000 Filipinos suspected of being involved in illegal drugs under the Duterte administration’s war on drugs.

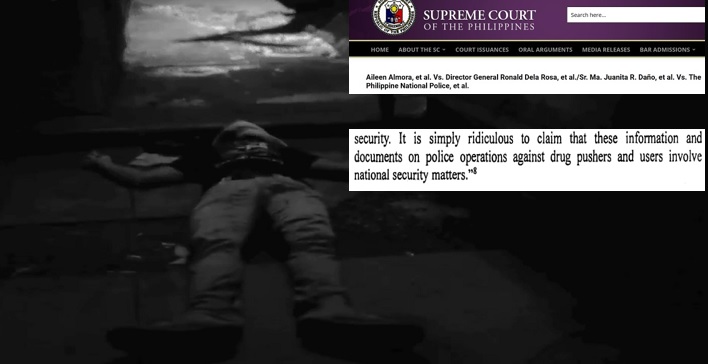

Recognizing that while the Philippine government has launched an investigation into the killings, the ICC said it has failed to “take meaningful steps to investigate or prosecute perpetrators of [war on drugs] killings” and it appears that “only a handful of ‘token’ cases — focused on low-level, physical perpetrators — have proceeded to trial.” It noted that only the murder of a 17-year-old student from Caloocan City, Kian Loyd Delos Santos, has proceeded to judgment.

Even in the Delos Santos case, the ICC noted that no official was investigated “for ordering, planning or instigating” the killing. “Senior or commanding officers implicated in killings have been only temporarily relieved of duty and later moved or even promoted,” it said.

In short, the local investigations were not deep enough to pinpoint accountability from the higher officials. It can be described as “mema” in the lingo of the millennials. Me masabi lang na may ginagawa! The reluctance to dig deeper into the killings is obvious.

If they’re serious, why can’t the investigating agencies be straightforward to say that they’ve looked deep and wide into the killings and found Duterte, Dela Rosa and other officials to be without fault?

Why is the ICC so interested to come in and investigate?

In view of the government’s perceived failure to take steps to investigate or prosecute the killings, the ICC said it wants to “obtain a full picture of the relevant facts, their potential legal characterization as specific crimes under the jurisdiction of the court, and the responsibility of the various actors that may be involved.”

Fatou Bensouda, the former ICC prosecutor, cited the government’s failure in invoking the Rome Statute’s core principle of complementarity to justify her request for the ICC to step in.

In June last year, Prosecutor Karim Khan, Bensouda’s successor, said in his request for the resumption of the ICC probe that “the Philippines has not asserted that it is investigating any conduct occurring in Davao from 2011 to 2016, any crimes other than murder, any killings outside official police operations, any responsibility of mid- or high-level perpetrators, or any systematic conduct or state policy.”

He also said the ICC could not defer to the government’s investigation because most of what it has been doing “relates to administrative and other non-penal processes and proceedings which do not seek to establish criminal responsibility.”

Why should Duterte and Dela Rosa be investigated?

In her request for investigation before she retired in June 2021, Bensouda said “the killings were committed in connection with a formal anti-drug campaign,” which Duterte declared upon his assumption into office and Dela Rosa carried out as chief of the Philippine National Police.

Bensouda’s 57-page request for investigation noted several of Duterte’s public statements encouraging the killings and promising immunity to those who would do so. She said that her three-year preliminary examination of the killings of some 12,000 to 30,000 suspected drug personalities under Duterte’s drug war showed that police officers conspired with some government officials, as well as vigilante groups, to carry out the killings of alleged drug suspects since the 1980s.

The probe that Khan has been authorized to investigate will cover only those that happened from Nov. 1, 2011 to March 16, 2016, when Duterte was mayor of Davao City, until his withdrawal of the country’s membership from the Rome Statute — the treaty that established the ICC — took effect.

Without the ICC’s criminal investigation, Khan said “there is a real risk that Rome Statute crimes committed in the Philippines will go uninvestigated and unpunished.”

Philippine officials use big words such as intrusion and sovereignty to block the ICC probe and shield Duterte, Dela Rosa and other high-ranking officials from criminal responsibility for the killings. But they fall short of assuring reasonable justice for the families of the victims of the war on drugs.

While they were quick to defend Duterte et al. from being prosecuted, they were too slow in taking up the cudgels for the victims who are mostly from poor families. That does not give a picture of a well-functioning and independent judicial system.

The ICC says it is coming in because the investigation by the national agencies “do not sufficiently mirror” the international tribunal’s own probe.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.