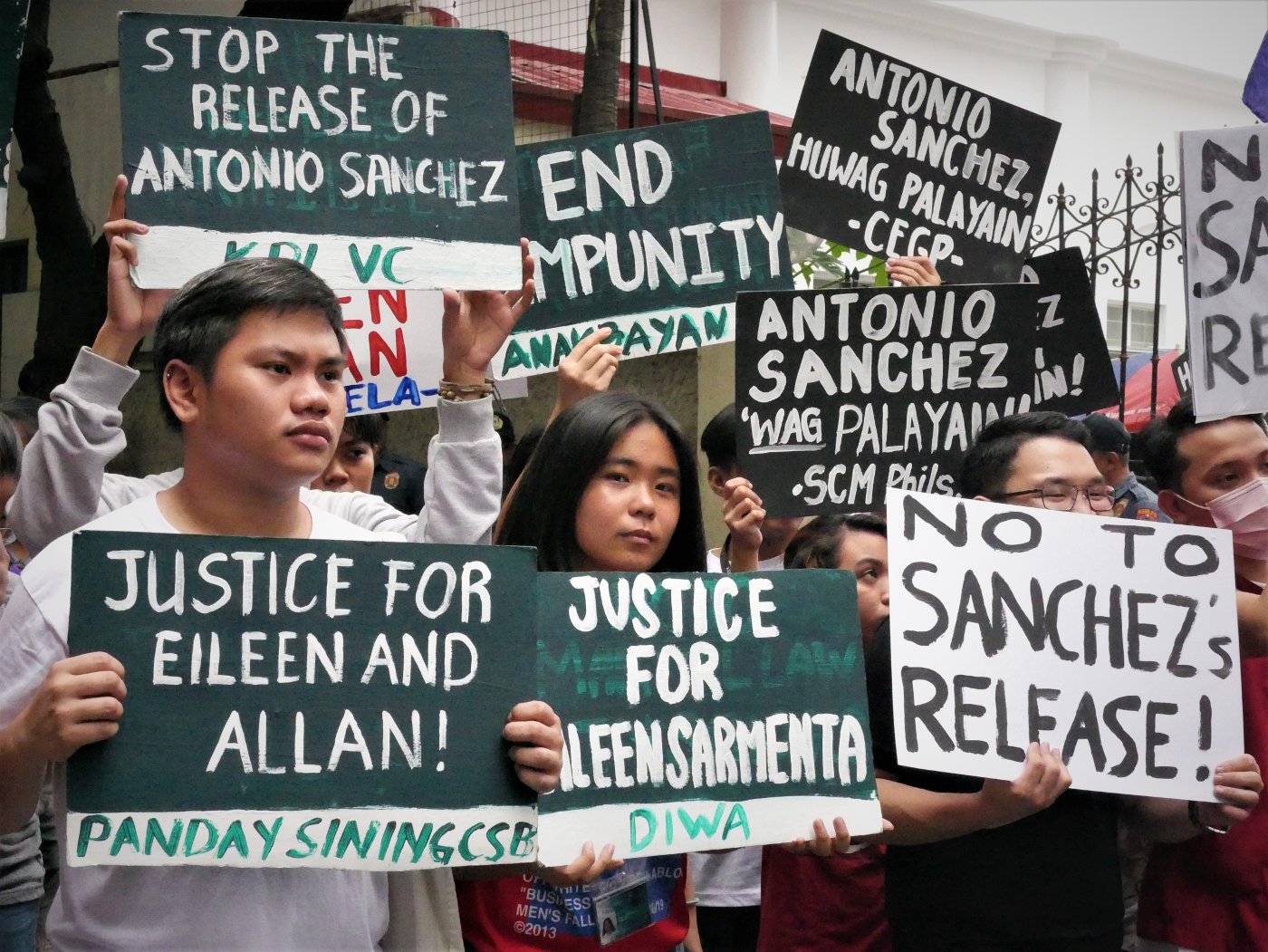

A debate on the implementation of a law that increases the good conduct time allowance (GCTA) of prisoners ensued after the earlier reported pending release of convicted rapist-murderer former Calauan Mayor Antonio Sanchez. The Justice Department and Bureau of Corrections (BuCor) initially identified Sanchez as among the 11,000 inmates who may walk free from prison in the next two months.

Republic Act 10592 was enacted in 2013, amending RA 3815 or the Revised Penal Code (RPC). The law increased the GCTA of prisoners to be credited in the service of their sentence. Last June, the Supreme Court (SC) ruled that the law should apply retroactively.

Some lawmakers, including Senate President Vicente “Tito” Sotto III, are calling for a review of the law.

But what exactly is GCTA? Can all prisoners benefit from it?

Here are four things you should know.

What is good conduct time allowance?

Good conduct time allowance or GCTA is a sentence reduction provision afforded prisoners who show good behavior.

It has been in existence since 1906. Act 1533 provided for the “diminution of sentences imposed upon prisoners” in consideration of good conduct and diligence.

Citing a 1908 decision, the SC said the law served a double purpose: to “encourage the convict in an effort to reform” and “induce…habits of industry and good conduct” in the person beyond one’s sentence, and “aid to discipline” various jails and penitentiaries.

Twenty-four years later, the RPC, a legal code governing crimes and their punishment, was signed into law, incorporating good conduct time allowances for “any prisoner in any penal situation.”

What is RA 10592 and how does it work?

In May 2013, then President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III signed RA 10592, amending Articles 29, 94, 97, 98, and 99 of the RPC, which sought to:

- expand the application of the GCTA to those under preventive imprisonment or those detained prior and during criminal trial, who are deemed too dangerous for release;

- increase the number of days that may be credited for GCTA;

- allow an additional sentence deduction of 15 days for each month of study, teaching, or mentoring service; and

- expand the special time allowance for loyalty and make it applicable to those under preventive imprisonment.

In cases of “special circumstances,” such as calamities, prisoners who, after evading preventive imprisonment or the service of their sentence, give themselves up to authorities within 48 hours after the “circumstance” had passed, will get a “loyalty” deduction of one-fifth of their sentence.

This means, prisoners who have evaded service due to fire, earthquake, explosion, or other catastrophes must surrender within two days from authorities’ declaration that such events are no longer present to qualify for the loyalty deduction.

Section 5 of the law says the BuCor director, the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology chief, and/or the warden of a provincial, district, municipal or city jail “shall grant allowances for good conduct.”

Last June, the SC granted the petition filed by New Bilibid Prison inmates, voiding Sec. 4, Rule 1 of RA 10592 Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR), which states that the grant of time allowance of prisoners for good conduct, study, teaching, and mentoring service, and loyalty “shall be prospective in application.”

The High Court ruled that the law should be applied retroactively, meaning those detained or convicted before RA 10592 was passed should also be covered by, and, therefore, potentially benefit from, the law.

The ruling is in accordance with Article 22 of the RPC, which states that penal laws “shall have a retroactive effect insofar as they favor the persons guilty of the felony, who is not a habitual criminal.”

Who can benefit from the law?

Inmates who display “good behavior and [have] no record of breach of discipline or violation of prison rules and regulations” may be eligible for GCTA, according to the BuCor operating manual, as cited in the SC decision.

The IRR of RA 10592 defines good behavior as:

“the conspicuous and satisfactory behavior of a detention or convicted prisoner consisting of active involvement in rehabilitation programs, productive participation in authorized work activities or accomplishment of exemplary deeds coupled with faithful obedience to all prison/jail rules and regulations”

Source: Supreme Court, G.R. No. 212719/G.R. No. 214637, June 25, 2019

Over the past years, Sanchez was found to have violated jail policies, according to reports from Philstar.com, Rappler, and CNN Philippines.

In 2006, a complaint was filed against Sanchez for allegedly possessing shabu and marijuana.

In 2010, a kilo of shabu worth P1.5 million was discovered in one of the Blessed Virgin Mary statues inside his cell. Five years later, an air-conditioner, flat-screen television, and refrigerator were seized from his cell.

Sanchez also tested positive for illegal drug use, according to a BuCor report.

Who are excluded from the law?

Recidivists or those who “have been convicted previously twice or more times of any crime,” habitual delinquents, escapees and persons charged with heinous crimes are excluded from its coverage, according to section 1 of RA 10592.

The law, as well as RPC, however, does not define what constitutes a “heinous crime.”

Under RA 7659 or the Death Penalty Act, heinous crimes are:

“grievous, odious and hateful offenses and which, by reason of their inherent or manifest wickedness, viciousness, atrocity and perversity are repugnant and outrageous to the common standards and norms of decency and morality in a just, civilized and ordered society.”

The Death Penalty Act, which was repealed in 2006, classified murder and rape as “heinous crimes” that may be punishable by death.

In 1995, Sanchez and six others were sentenced to seven terms of reclusion perpetua, for the brutal rape and murder of University of the Philippines Los Baños student Eileen Sarmenta and for the torture and murder of Allan Gomez, another student, two years prior.

Under the RPC, the maximum detention period is 40 years, regardless of the number of terms that one must serve. This means Sanchez will serve only 40 years in prison at most, even if he was sentenced to seven terms of life imprisonment.

In 1996, the court convicted Sanchez and three others of double murder of father and son Nelson and Rickson Peñalosa. Sanchez was already in jail then for the rape-slay of Sarmenta and the killing of Gomez, according to Inquirer.net, Philstar.com, and ABS-CBN News.

In 1999, the SC affirmed the lower courts’ rulings against Sanchez for the Sarmenta-Gomez rape-slay and the Peñalosas slay cases.

Sources

ABS-CBN News, Ex-Calauan mayor Sanchez, convicted for 1993 rape and murder, set for release, Aug. 21, 2019

Philstar.com, Ex-mayor Antonio Sanchez set for release, Aug. 21, 2019

Interaksyon, Rapist-murderer Antonio Sanchez is about to walk free, and people are furious, Aug. 21, 2019

Official Gazette, Republic Act 10592

Lawphil.net, Act 1533

Chan Robles Virtual Law Library, Act 1533

Official Gazette, Republic Act 3815

Bureau of Corrections, Operating Manual

Philstar.com, Good behavior? Prison violations, murder convictions mar Sanchez’s record, Aug. 22, 2019

Rappler.com, BuCor changes tune: Sanchez may not be freed soon after all, Aug. 22, 2019

CNN Philippines, Family of Antonio Sanchez’s victim questions convict’s supposed good behavior in Bilibid, Aug. 22, 2019

Official Gazette, Republic Act 7659

Inquirer.net, Antonio Sanchez was convicted of 2 other murders, Aug. 22, 2019

ABS-CBN News, Sanchez had sought clemency, but was denied due to ‘gravity of offenses’, Aug. 23, 2019

Supreme Court, G.R. No. 121039-45, January 25, 1999

(Guided by the code of principles of the International

Fact-Checking Network at Poynter, VERA Files tracks the false claims,

flip-flops, misleading statements of public officials and figures, and

debunks them with factual evidence.

Find out more about this initiative and our methodology.)