By AMER R. AMOR

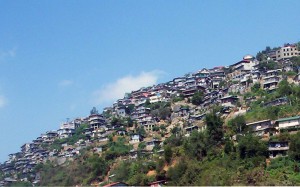

AFTER the earthquakes that hit Japan and New Zealand, volcanologists are drawing attention to the possibility a big one could hit Baguio, but the city lacks a comprehensive disaster management program and has in fact repeatedly failed to enforce environment rules that could mitigate disaster.

AFTER the earthquakes that hit Japan and New Zealand, volcanologists are drawing attention to the possibility a big one could hit Baguio, but the city lacks a comprehensive disaster management program and has in fact repeatedly failed to enforce environment rules that could mitigate disaster.

Baguio sits on four major fault lines: Mirador, San Vicente, Loakan and Burnham, according to a study by University of the Philippines-Baguio geology professor Dymphna Nolasco Javier. Four other earthquake generator faults surround the city: San Manuel, Tuba, Tebbo, and Digdig, which generated the destructive 1990 earthquake, the study showed.

But more than two decades since that 7.7-magnitude earthquake, the country’s summer capital remains unprepared for catastrophes. The 1990 earthquake left 305 people dead, more than a thousand people injured and thousands of houses in ruins.

This makes the city—named the country’s second most risk-prone after Marikina and Asia’s seventh—a disaster waiting in the wings, officials and residents alike fear.

Baguio demonstrated its lack of disaster prepardeness last August when a passenger bus plunged into a ravine in Sablan town 12 kilometers away. The City Disaster Operations Center (CDOC) responded with only five rescue kits in an attempt to save 50 lives.

Only 10 passengers survived that accident. Looking back, more lives could have been saved had the CDOC team been better equipped, said CDOC head Archiemor Ellamil. The CDOC is the implementing arm of the City Disaster Coordinating Council, now renamed the City Disaster Risk Reduction Management Council.

The Sablan accident was not the only time that the center’s lack of equipment hampered rescue operations.

At the height of typhoon “Pepeng” that slammed northern Luzon in October 2009, the Office of Civil Defense-Cordillera (OCD-CAR) lent the city ropes and shovels because it did not have enough for the rescue operations, said OCD-CAR regional director Olive Luces, who considers the CDOC more a communications group than an operations center.

Janice Singiten, a CDOC volunteer for almost 10 years and who was part of the Sablan team, said the dismal absence of equipment somehow negates their rescue skills. The CDOC has only one ambulance and one pickup vehicle to respond to emergencies, she said.

Yet the city has a population of 325,880 crammed into a space of only 55 square kilometers. Baguio’s population doubles during the hot season, especially Lent.

Because of the high presence of natural hazards, the World Bank has identified Baguio as one of Asia’s seven risk-prone cities. About 90 percent of the city is vulnerable to natural hazards because of its unique topography, data from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources–Cordillera (DENR-CAR) reveal.

Both Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology director Renato Solidum and DENR-CAR’s chief geologist Fay Apil do not rule out the possibility of a strong earthquake hitting Baguio again.

In the 1980s, a study by DENR-CAR declared the city geologically hazardous because of its sensitivity to seismic shakings. Rain easily penetrates the ground because the soil is generally porous and permeable, making Baguio highly susceptible to landslides and earthquakes, the study further said.

But residents continue to inhabit some of the most dangerous places in the city, such as Barangay Crystal Cave where 18 sinkholes have been identified. Some have even built hosues directly above a sinkhole.

Residents there have refused to vacate the area despite warnings, and even got the courts to issue temporary restraining orders that allowed them to stay put.

Laxity in enforcing the zoning ordinance also exposes residents to more risks should a disaster strike.

The zoning ordinance, for example, imposes a height limit of six stories for commercial buildings. But the same ordinance created the Local Zoning Board of Adjustment and Appeals that could exempt projects that supposedly will not adversely affecting public health, safety and welfare, and will support economic based activities.

The board granted exemptions to 80 of the 119 requests filed from 2004 to 2008, a report showed.

Zoning provisions on parking are also disregarded, especially within the central business district, resulting in vehicles clogging the city’s narrow thoroughfares.

Traffic congestion has hampered the movement of fire trucks, said fire officer Arsenio Palongdosan who drives the lone seven-drum capacity fire truck used for responding in narrow alleys in Baguio.

Not that the city has enough fire stations and firefighting equipment. Baguio only has one main station near Camp Allen, one substation in Barangay Irisan and six fire trucks, one of which is not functioning.

Under the city’s Comprehensive Land Use Plan for 2002 to 2008, four fire substations should have been, but were never built in Aurora Hill, Crystal Cave, Dontogan and Pacdal, all high-density areas, during the period. From 2005 to 2007, 199 fire incidents were recorded in Baguio, 106 of them structural fires.

These and other vulnerabilities make the adoption of a disaster management plan all the more necessary for Baguio. But the city does not have one, unlike neighboring Tuba and La Trinidad towns that, though poorer than Baguio, update their disaster management plans yearly.

Signed in 1978 by then President Ferdinand Marcos, Presidential Decree 1566 called for the establishment of the national program on community disaster preparedness and directed local government executives through the City Coordinating Councils to organize their disaster preparedness plan.

In 1995, Baguio passed Ordinance No. 27 creating the City Disaster Operations Center (CDOC) but not a disaster management plan.

Cornelia Lacsamana, head of the City Environment and Parks Management Office, said the city only has an action plan that is not extensive and just includes crowd control and fire safety situations.

A disaster management plan could and should have been incorporated into the city’s Comprehensive Land-Use Plan, which itself needs updating, she said.

Lacsamana also said, “We should have a disaster coordinating office year-round, with a well-trained technical man on top of the situation. It is easy to mobilize volunteers, but we do not have the technical capability.”

She said that all the people who work at the CDOC, save for Ellamil, remain volunteers and none of them are well-trained to handle disasters.

Luces said the City Coordinating Council in Baguo hardly functions. She noted that a number of those in the council were put there only for compliance purposes and do not know what to do.

“The council could’ve met earlier to mitigate the situation (during Pepeng), but they were not fully activated and the only visible entity then was the communications group. In terms of structure, it was not clear to everyone who’s going to do what,” she said.

Part of the CDOC’s job is to regularly conduct seminars, training courses and other mitigation measures in high-risk areas.

Ellamil said the center has run disaster-preparedeness seminars for barangay captains. Earthquake drills have not been conducted of late for businesses only because “new business establishments have not yet requested” for these, he said.

But Luces said most of the center’s disaster-preparedness trainings and earthquake drills are actually projects of her office, the OCD-CAR, which fields all its five regular officers for this purpose.

She said the CDOC even tried to pass on to her office the expenses for training the responders. “We already orient them on how to conduct an earthquake drill, we shouldn’t be shouldering expenses like that,” she said.

Residents of Barangay Irisan interviewed for this report said they have not heard of a disaster-preparedness campaign or an earthquake-drill conducted by the CDOC in their area recently. Irisan, the most populated barangay in Baguio, lies in a high landslide susceptible area.

Luces also found the training for barangay captains ineffective.

At the height of Pepeng, the OCD-CAR visited Camp Lagoon, so-called because of persistent flooding in the area.

“CDOC assured me they were closely monitoring the flood level there. My team, however, found out the water level had already become alarming, so they tried to mitigate the situation by removing all the garbage they could, with their bare hands, while the barangay captain did nothing and merely looked them do the dirty work,” said Luces.

She added, “They need to have a disaster management office, put the right people there, (and) deploy the right people at the right place at the right time.”

Should an earthquake occur again, Phivolcs’ Solidum said its impact can be minimized if residents exposed to the natural hazards are aware of the risks and are prepared to respond to them. The key, he said, is awareness.

Apil, however, recalled that when the DENR-CAR invited local government units to an information education discussion before Pepeng struck, nobody from Baguio City showed up.

Luces also lamented that invitations for a contingency planning sent in 2010 to then Baguio Mayor Peter Rey Bautista went unheeded.

But Evelyn Cayat, head of the City Planning and Coordination Office (CPCO) which is responsible for implementing the city’s Comprehensive Land-Use Plan, laughs off the possibility of a killer quake occuring soon. She cited a study that shows an earthquake of the same magnitude happening only every 80 years.

She also insists: “We have a city disaster coordinating council. We also have an emergency medical service which is not present in other local government units. We are actually well-equipped to handle disasters.” #

(Amer Amor, a masteral student at the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication, wrote a longer version of this report for his Investigative Journalism class taught by VERA Files trustee Yvonne T. Chua. Amor teaches at UP Baguio.)