Fear has grown among barangay leaders of San Andres Bukid in Manila. With police out of the picture, they dread that all hell would break loose, and the area might revert to being a den of criminals.

The 13 barangay captains claim that public order was restored in San Andres Bukid as a result of the administration’s war on drugs, but this could fall apart should a petition for the writ of amparo be granted.

Tension filled a dialogue in the barangay hall of Barangay 770 on Oct. 25, with the captains puzzled as to what this petition, filed before the Supreme Court on Oct. 18, entails.

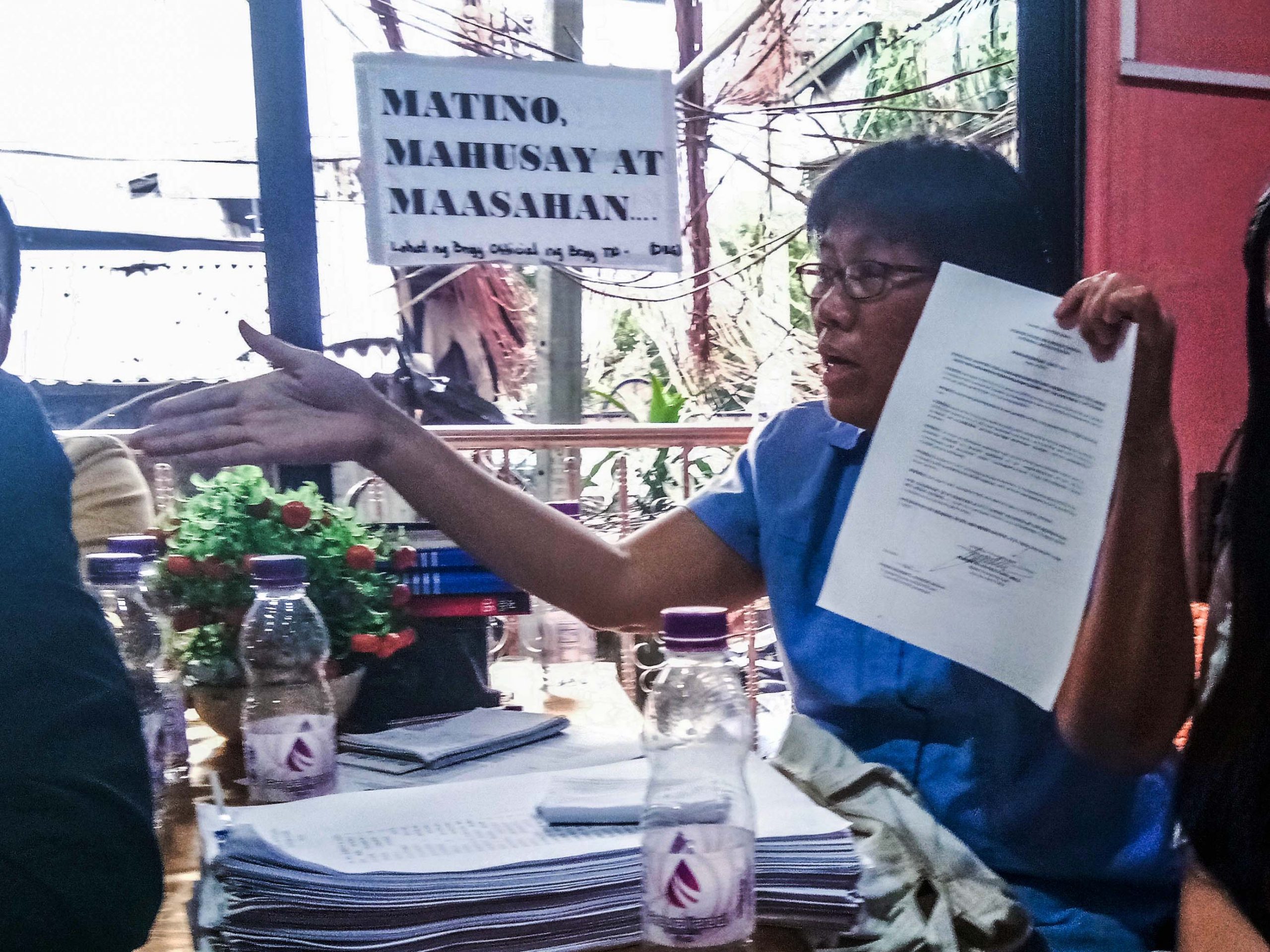

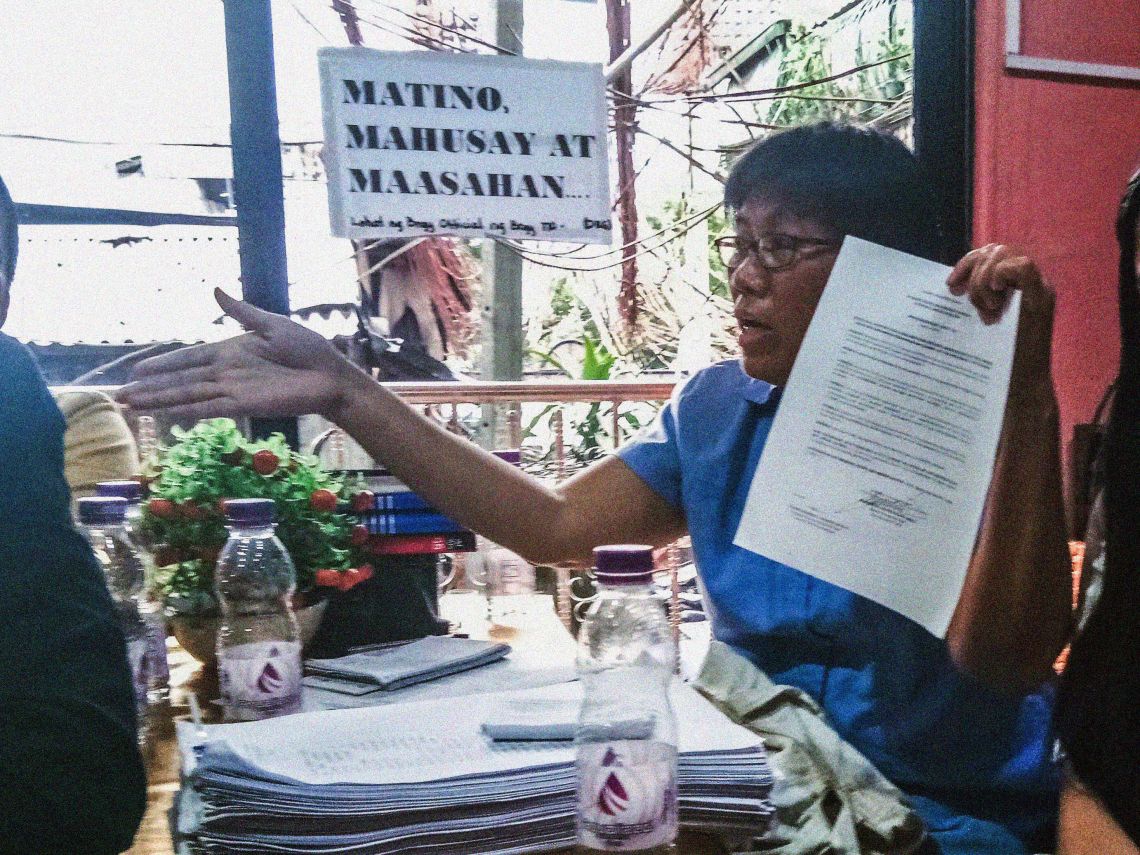

At the receiving end of their questions was Sister Juanita Daño, the lead petitioner, and lawyers of the Center for International Law (Centerlaw), which filed the writ of amparo. (See Residents from 26 barangays file protection vs police)

Sister Juanita Daño, the lead petitioner for an issuance of the writ of amparo, talks to the barangay captains.

Lawyer Cristina Antonio of Centerlaw, speaking in behalf of Daño, clarified the document only seeks protection to ensure the petitioners’ safety after their right to life had been violated and threatened by officers of the Manila Police District (MPD) Station 6.

Yet, the barangay captains see no problem with the heightened police presence. They even say crime has decreased in their areas, thanks to what they say has been a robust coordination with local police.

“Thank God, we are now at peace and relaxed. Why? Because there’s a system between the police and barangay in our community,” one barangay captain said in Filipino.

One call and the police would respond right away, she added, to which the other chairs agreed. The worst thief in San Andres Bukid, they say, is now in jail.

The change in the jurisdiction of the anti-illegal drug operations from the Philippine National Police to the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency, they pointed out, only worsens the situation.

“We’re scared that the police are stripped of their rights. We can’t do the anti-drug operations without police,” added one of the captains.

He asked what protection Centerlaw can give residents if they were going against the addicts themselves, now that the police are “gone.”

Antonio said there’s always an option to file a blotter report when a crime is committed. “We are not mad at the police. We believe in institutions.”

But the sworn statements in this 59-page petition prove that the community cannot be deaf in situations where the police are the perpetrators, she said.

“That’s why we are asking for protection. Because the residents are scared, and they need the court to tell the police and remind them that people should not be scared of them,” she added.

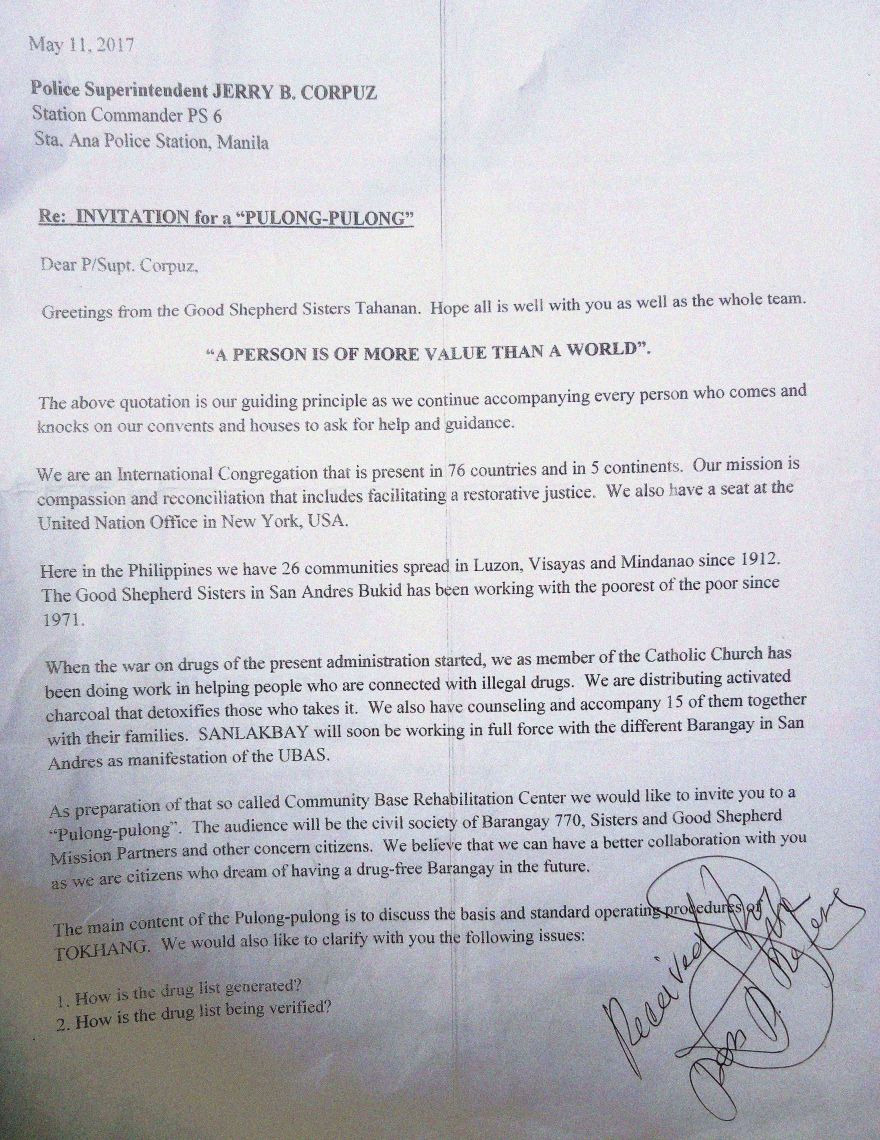

Daño said she had also made efforts to request a dialogue with MPD Station 6 before the petition was even filed. Her letter sent in May was received by the police but never acted upon.

The request letter received by the Manila Police District Station 6

Antonio understands the barangay captains’ dilemma, as they only found out about the petition after it had been filed. “They’re caught between the devil and the deep blue sea. They’re scared.”

Indeed, the petition, as soon as it was filed, seemed to have caused panic both among the barangay captains and police.

Some captains brought petitioners to their offices, questioning why their names were written on the petition. Two captains also pointed out there was no petitioner coming from their barangays, so their names shouldn’t be on the list.

But as Antonio told the leaders, their names, written on page 14 of the petition, were placed just to specify which 26 barangays the petition refers to. In short, they were neither petitioners nor respondents.

A petitioner shouldn’t have to notify anyone, she added. One can just go to court and file a case without permission from the barangays.

“And that’s his or her right,” Antonio explained. “He has the right to bring any grievance in any proper forum, and he or she doesn’t have to ask permission from anyone.”

When a case is filed, she said it should not be discussed outside court except through a proper channel, or with a counsel.

By asking resident-petitioners to appear in their offices, the captains in effect have been acting in behalf of the police, which is illegal and they may be cited for contempt, Antonio said.

Had the police been at the dialogue, too, they would have been confronted as to why at the wee hours of Oct. 21, three days after the petition filing, two police officers barged in on one of the petitioners’ home, asking her to write on a piece of paper that extrajudicial killings are fine.

“They were asking for her ID,” Antonio said. “She was compelled to write the statement.”

While the police had given up after the petitioner told them she had no ID, the experience is a chilling threat to the residents, Antonio said.

“It’s ironic (that) it’s scary to file this case and to come out in the open,” she said.

Through the end of her explanation, the lawyer asked the barangay captains if she had clarified the petition enough. One barangay captain said, “Yes, this (discussion) is good,” to which the others nodded in agreement.

For the resident of San Andres Bukid, the decision now rests on the Supreme Court.

“Because of this move, there is a mantle of protection not just from the court but also the awareness that this petition brings,” Antonio said.

She hopes other lawyers will do the same in other parts of the country.

Daño, for her part, says she will not rest until the petition is granted.

It is no secret that the nun’s life is in danger now more than ever. She has been living in the community since 2011 as a social worker, and has overstayed almost four years now.

But while she is scared of the police, it is a mission she will never relinquish.

“My fear of the police is overshadowed by my fear of God,” the nun said. “When I die, I fear I won’t have anything to say when He asks me what I did when the killings happened.”