Siargao island

The sun has just risen over the surfboards lined up along the white-sand shore of Cloud 9, the world-famous surfing spot here in the town of General Luna. Local and international tourists are doing a dry run with their surfing instructors before riding the ocean waves on a warm, early morning in August.

It still feels like summer. Here in Siargao, it always feels like summer.

Jessie Noguerra started surfing here when he was 16, taught by older local surfers whose names are now well known in local and international tournaments. Back then, he says, they borrowed surfboards and skipped lunch to ride the waves.

“We enjoy it (surfing) very much. After you first try it, you want to do it again and again, until you find yourself surfing every day,” Noguerra said in the Cebuano language spoken in central and southern Philippines. “The best feeling is when you finally catch a wave on your own, no longer with an instructor assisting you from behind.”

At 32, Noguerra is now the one teaching others to surf in this island that is commonly called the Philippines’ surfing capital and ranks among the top global destinations for recreational and competitive surfing, as well as beach holidays.

A year after super typhoon Odette (international name: Rai) ravaged Siargao and some 10 months since the Philippines reopened its borders during the COVID-19, more tourists have been making their way back to the island. In October 2022, the Siargao International Surfing Cup was held here after a two-year break due to the pandemic.

But the sun, sea and waves that are Siargao’s trademark were farthest from the locals’ minds one year ago.

On 16 December 2021, Odette – the strongest typhoon that hit the Philippines that year –-made its first landfall in the country. Siargao, located in the northeastern coast of southern Mindanao region, bore the brunt of this Christmas ‘surprise’ storm, which made eight more landfalls across Mindanao and the central Visayas region with torrential rains, storm surges, floods. Its maximum sustained winds of up to 195 kilometres per hour earned it a Signal No 4 warning, just one level below the maximum, and gusts reaching 270 kph.

By the time the typhoon exited after two days, it had led to 409 deaths, displaced 641,000 people and damaged or destroyed more than 2 million homes across the country of over 115 million people, according to United Nations data in January 2022.

Odette’s fury caught Siargao residents off guard, since the last devastating typhoon that affected their hometown was Nitang (international name: Ike) in 1984.

Memories of Odette’s fury

“It was as if a tornado had entered the house,” Noguerra said, recalling how Odette’s winds shattered the windows of the concrete home his family had sheltered in, and sent shards of glass flying about.

One fragment of glass got into his left eye, requiring treatment. His wife, then six months pregnant with their first child, hid behind a thick bed cushion.

Several meters away from the shoreside stands the now-restored Cloud 9 boardwalk. Though now reconstructed, with the reuse of some materials from the original one, the sight of it remains a reminder of destruction to Noguerra every time he goes to work.

Towards the main entrance from the boardwalk, 48-year-old Ritchel Ambalgan tends to her reconstructed ‘sari-sari’ store (corner store), which reopened in June. “This was all gone! We just recently built this again from scratch,” Ambalgan said in the Cebuano language spoken in central and southern Philippines.

Noguerra and Ambalgan were among the 12 million people that the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs says were affected by Odette.

Noguerra rebuilt his house with financial help from former surfing students. “I have great gratitude for them,” he said. “We are doing better right now because we already recovered. There are many tourists again and it’s like we are going back to normal days,” said Ambalgan.

‘Stronger and better’

Siargao’s tourism industry, a major income earner for the island community, took a direct hit from Odette – in the middle of the sharp drop in visitors during the pandemic.

General Luna town accounted for three-fourths of the economic damage on the entire island, or 1.2 billion pesos (23.9 million US dollars in December 2021), says data from the Post Disaster Needs Assessment by the Philippines’ tourism department.

Half of the 5,494 tourism workers on Siargao affected by the typhoon were from General Luna, as of February 2022. The island itself is home to over 136,000 people.

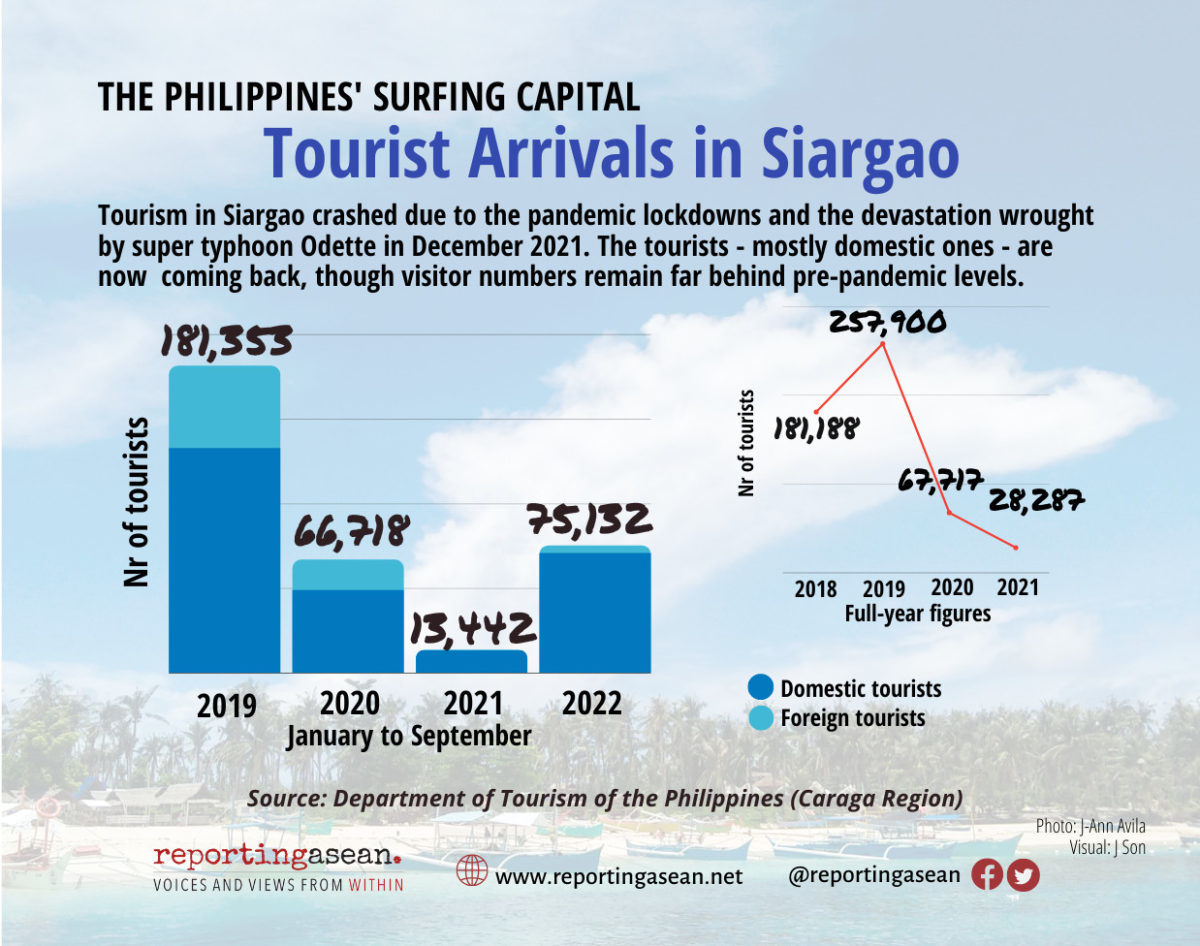

Siargao received 75,132 tourists – 94% of whom were domestic ones – from January to September 2022, official figures show. This is just over 40% of the total 181,352 tourist arrivals in the first three quarters of 2019, before the pandemic.

Tourism is certainly what sustains General Luna, says its vice mayor, Romina Rusillon-Sajulga.

“That’s why we really cleaned up the entire town,” she said in an interview. “We did not have the equipment, so what we did was contact all the contractors with projects here,” she said, adding that several of these helped out by lending equipment and providing gasoline. “We’re going to rebuild it (the town) stronger and better.”

Siargao’s jump-off point, from where tourists depart to go island-hopping to enjoy clear green lagoons and coves, was first on the reconstruction list, followed by the Cloud 9 boardwalk.

The rebuilt boardwalk has posts made of cement and planks made of PVC, features that should make it “stronger than before”, Sajulga explains. “But it’s the same route (of the boardwalk), just different material. We just still lack the budget for the (viewing) tower.”

Restarting the surfing tournaments is part of the local government’s ‘Bangon Siargao’ (Rise, Siargao) recovery programme. Dapa, which is located next to General Luna and is the tourists’ entry point to Siargao via ferry, hosted its first-ever National Dragon Boat Regatta in July.

Its local officials have grander plans for their town – if General Luna is well-known for surfing, Dapa aims to be known for diving.

Developing tourism infrastructure would provide more jobs, they say. Despite Odette, local officials and residents remain focused on tourism as a main economic resource.

“Odette happened 37 years after Nitang so we thought maybe the next one is still after 47 years,” Sajulga jokingly said. “But you know, with climate change, we really don’t know.”

Changing typhoon patterns

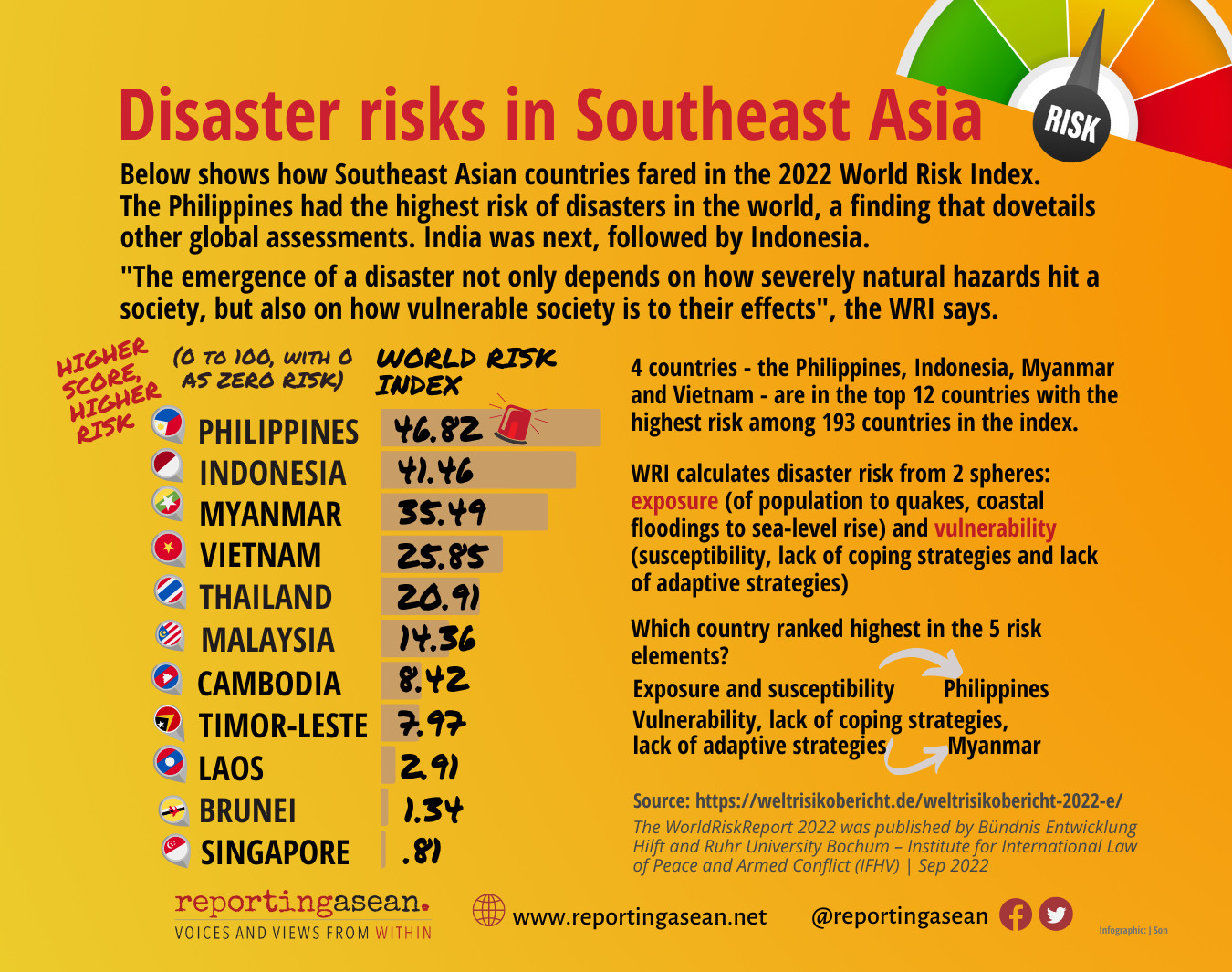

The Philippines ranks highest (46.82 on a scale of 0-100) among 193 countries in the 2022 World Risk Index.

While the country is used to getting typhoons of up to 20 in a year, these have been passing through at periods of time outside the typical storm season of June to October and roaring through regions, such as the Philippines’ southern parts, that did not regularly have them many years ago.

There have been conflicting statements from scientists studying typhoon behavior in the context of today’s climate, explains Bernard Alan Racoma, a Filipino researcher in meteorology as well as oceans and climate.

“Some scientists say that tropical cyclones are moving more poleward, in the recent years start(ing) to form further away from the equator,” he explained, a trend that would tend to point to fewer chances of such making landfall in the Philippines. But others say that such typhoons have been moving nearer, “albeit ever so slightly”, to the equator during October to December, which would mean the reverse – that tropical cyclones are more likely to hit the country.

“In short, it’s complicated,” said Racoma, who is pursuing a dual doctoral degree in meteorology at the University of the Philippines and in atmosphere, oceans and climate at Britain’s University of Reading.

But it is a fact that Mindanao has experienced an increase of passages by typhoons within the last decade. From 2012 to 2020, Mindanao saw an unprecedented 480% increase in ‘Christmas typhoon’ events – such as Odette – that come around December to February.

At a time of climate emergency, the Philippines needs to use, for disaster-related planning and risk assessment, data that reflect more closely what has been actually happening around typhoons and the probable hazard scenarios that arise from these, explains Alfredo Mahar Lagmay, a geologist who is executive director of Project NOAH (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards).

It can no longer refer to worst-case scenarios around typhoons in the past, and plan and act on the assumption that only events that have happened before can possibly happen today, or later on.

“We cannot underestimate the hazards. We have to represent in scenarios the hazards of the future, especially (given) that there is a threat of the adverse impacts of climate change,” explained Lagmay.

He advocates for the country’s use of maps that assess “probabilistic risk”, which create hazard scenarios bigger than what it has experienced or what is in its historical record. Such maps are part of the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction’s guidelines, and are mentioned in the country’s Climate Change Resolution 2019-001.

“Unfortunately, until now, it is still not yet being implemented on a national scale, because the maps that we have on a national scale, or at least the official maps that are recommended by the government, are the deterministic maps,” Lagmay added. Unlike probability-risk maps, “deterministic” ones only refer to worst-case, often single-situation, scenarios of the past, he says.

The use of such maps has already been proven unreliable in disasters such as super typhoon Yolanda (known as Haiyan internationally) in 2013, which hit the central Visayas region, he continues. (Yolanda, which came in November, was among the most powerful typhoons ever recorded globally. Described as the deadliest in the Philippines, it led to 6,300 deaths.)

The evacuation centres in central Tacloban City that were destroyed by Yolanda’s storm surges were located in areas identified as non-critical ones in the hazard maps long used in the Philippines, Lagmay explains.

Project NOAH, whose website has disaster prevention information based on “near real-time weather data” and hazard maps for floods, landslides and storm surges, is managed by the University of the Philippines’ Resilience Institute.

Formerly the flagship research programme on disaster prevention and mitigation set up in 2012 under the national science and technology department, it was shut down in 2017 by the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte due to “lack of funds”.

‘Help us recover’

“If you’re going to visit Siargao, you’re not only going to enjoy Siargao but you’re going to help us recover,” explained Sajulga, whose dream is to the island becoming the number one destination among local tourists.

Bleeding hues of yellow and orange at dusk, the sun descends beyond Catangnan Bridge in General Luna as a couple takes in the scenic view while their four-year-old son, Remrem, plays with ‘racing robot’ toy on the pavement. “He thought the heavy rains days after Odette’s landfall were another typhoon,” his mother recalled.

Typhoon bulletins now make 62-year-old Erma Aurora, who lives near the seawall, nervous. “Others joke about us being already used to typhoons, but that’s only for the small ones,” she said in the Surigaonon dialect.

“They’re inevitable and we can’t escape them. We just have to accept whatever our fate is,” said boatman Xander Dole, who ferries visitors who go island-hopping.

Rexon Coro, who lives right behind the seawall with his wife and 11 children, added: “If another typhoon is coming, then we run again.”

(*J-Ann Avila of Reporting ASEAN is a fourth-year journalism student at the University of the Philippines.)