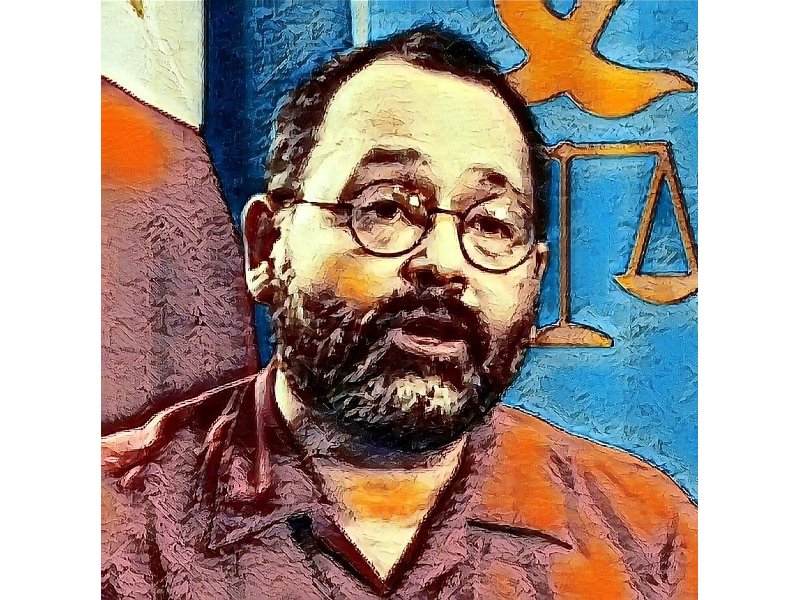

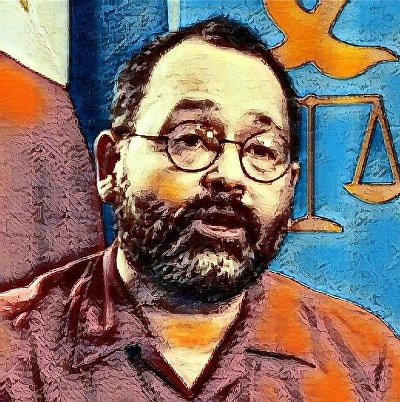

IT is doubly sad that Jose Luis Martin “Chito” Gascon succumbed to the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) at a time when the International Criminal Court (ICC) is about to begin formal investigation of alleged crimes against humanity related to the Duterte administration’s campaign against illegal drugs.

While those left behind at the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), particularly Commissioner Karen Gomez-Dumpit as officer-in-charge, have promised to continue “with equal fervor and sincerity” the work that Chito had started, things just won’t be the same without him.

For sure, President Rodrigo Duterte will seize the opportunity to appoint an ally to head the CHR, especially with the ICC probe in the air.

Chito’s death is indeed sudden and untimely. It was the first thing I saw on Facebook soon after I woke up on Saturday. I thought about his wife, Melissa, who I met while covering the House of Representatives in the early 90s and she was a staff in the office of then-representative Edmund Reyes of Marinduque. I thought about their young daughter, Ciara.

Chito was among the personalities I covered when I was starting in journalism in 1986 or 1987. He was in a tight race for the leadership of the Student Council at the University of the Philippines-Diliman under the Nagkakaisang Tugon (Tugon) party against now Sen. Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan of the Sandigan para sa Mag-aaral at Sambayanan (SAMASA).

The two student parties were organized at the height of the fight against martial law in the early 80s.

Many years later, the bitter rivals Chito and Kiko found themselves fighting common causes under the Liberal Party. Their former rival student parties have recently joined forces to support the presidential bid of Vice President Leni Robredo.

The first time I saw Chito, I had the impression that the mestizo-looking student leader was a snob. After hearing him speak in a protest rally, I was surprised that he could communicate clearly and eloquently in Tagalog. He was approachable and quite humble, and never a snob.

After Ferdinand Marcos was ousted in 1986, Chito was appointed as representative of the youth sector to the Constitutional Commission that drafted the 1987 Constitution. Later, he was appointed as youth sectoral representative to the House of Representatives of the 8th Congress during which he spearheaded the passage of laws such as the creation of the Sanggunian Kabataan and Republic Act 7610, a special law providing protection to children from abuse. He was the youngest member of both bodies.

Chito graduated from the University of the Philippines with an undergraduate degree in philosophy, then pursued a Bachelor of Laws degree that he finished in 1996. In 1997, he obtained a Master of Law degree in international law (specializing in human rights, law of peace, and settlement of international disputes) from Cambridge University.

From 2002 to 2005, Chito was an undersecretary for legal and legislative affairs at the Department of Education.

Before he was appointed CHR chairman in 2015, Chito served as a member of the Human Rights Victims Claims Board, the body responsible for administering recognition and reparation programs to the Martial Law Regime’s victims where he held a rank equivalent to Justice of the Court of Appeals.

It is also sad that Chito did not live long enough to see the proposed Human Rights Victims Memorial Commission implemented. Its budget is already included in the proposed P867.251-million outlay for the CHR for 2022.

Reading messages of sympathies to Chito’s family from the Department of National Defense (DND) and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) show the good character of Chito toward persons on the opposite side. He had entangled with them in cases involving alleged human rights violations by soldiers.

Following Chito’s death, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana said in a statement that the DND recognizes the great work done by the CHR under its late chairman.

“His tireless work as a human rights champion and the watchful eyes of the CHR further pushed the AFP to advocate and abide by the principles of human rights and International Humanitarian Law,” said AFP spokesperson Army Col. Ramon Zagala.

Even Martin Andanar, President Rodrigo Duterte’s Communications secretary, acknowledged that Chito’s death “is a loss of a pillar and a symbol of democracy and human rights of our nation.”

In 2017, Duterte attempted to pressure Chito to resign and even insinuated that he was a pedophile because of his focus on the killing of teenagers in the government’s bloody war on drugs.

But far from Duterte’s insinuation, Chito’s leadership was inspirational and nurturing, according to CHR spokesperson Jacqueline Ann de Guia. She said he impressed upon the CHR staff and fellow human rights workers the impact and value of their work, especially to those who have it least.

Chito is indeed one of a kind.

After several years, I was again surprised that he could still remember me. He even told me one time when I saw him at a coverage that he had met Sangeeta, a journalist-friend from Nepal who was with me in a fellowship in Honolulu in 2003.

The last time I saw Chito was in 2019 when I attended a consultation meeting with other media representatives and human rights advocates at the CHR office and he dropped by the conference room.

I could not avoid thinking that perhaps Chito did not get Covid-19 and succumbed to it had the government handled the pandemic better. How many more people will die due to incompetence in the government’s response to the pandemic?

Chito’s younger brother, Miguel, posted this on Facebook on Saturday morning, Oct. 9: “Sa dami mong laban, sa COVID pa tayo na talo! Love you Kuya! (In all the battles you fought, we had to lose you to COVID. I love you, brother!)”

Chito, 57, would have ended his seven-year term at the CHR in June 2022.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.