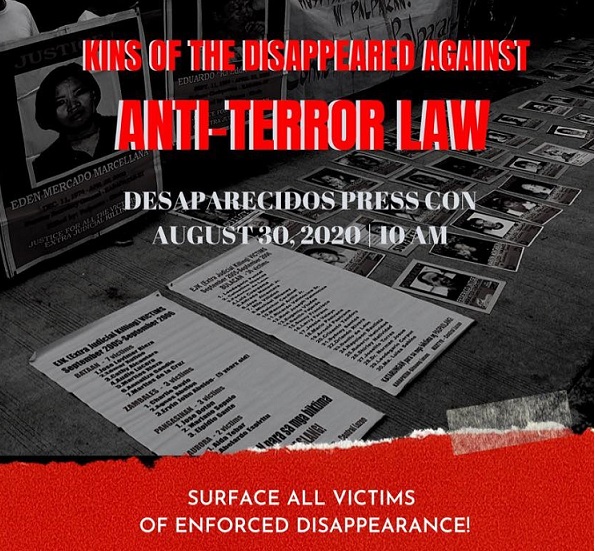

Families of desaparecidos marked the International Day of the Disappeared August 30 with deeper concern and sadness as the list has become longer in the last four years of the Duterte Administration.

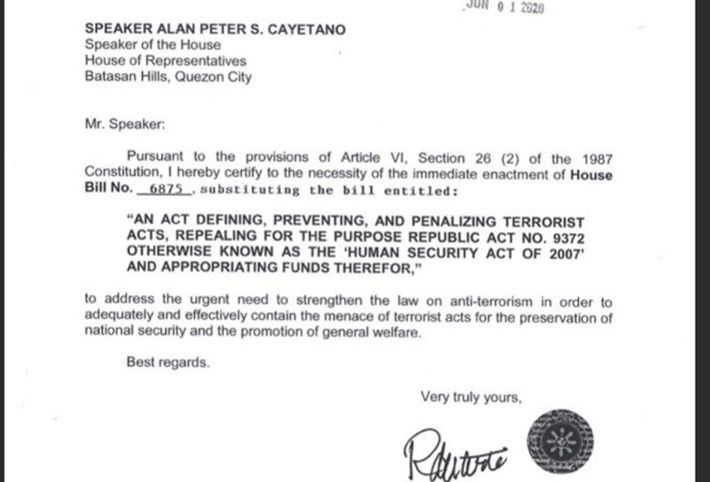

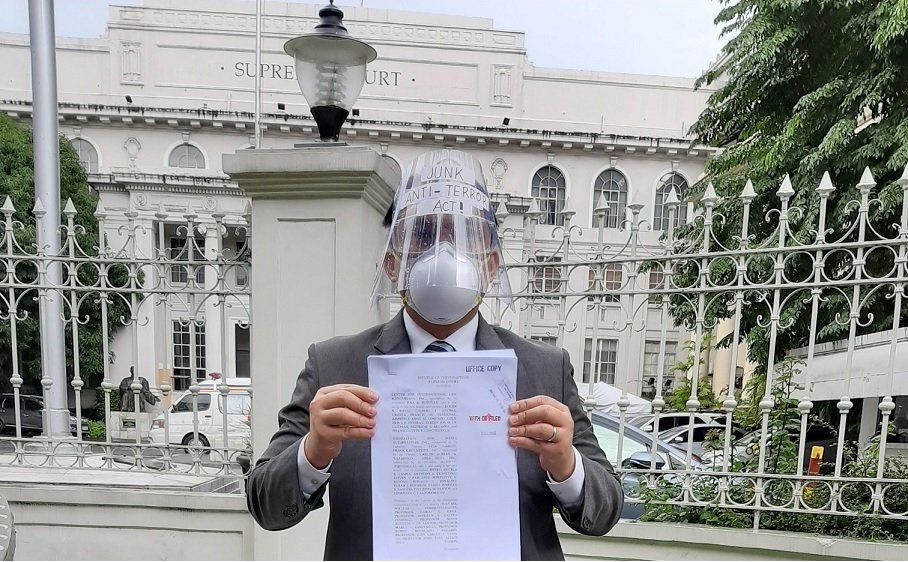

Erlinda Cadapan, Desaparecidos chairperson whose daughter Sherlyn has been missing since June 26, 2006, expressed the fear that the newly signed Anti-Terrorism Act “will serve as a fertile ground for increased cases of enforced disappearance.”

“We fear that Duterte’s terror law will enable State forces to resort to extraordinary measures such as abductions and enforced disappearances like what they did to my daughter to instill fear on its critics and activists as the government spins out of control because of the pandemic and the ailing economy,” Cadapan said during a virtual forum organized by Karapatan, an alliance for the advancement of people’s rights.

Sherlyn, together with fellow University of the Philippines student Karen Empeno, was abducted by persons suspected to be members of the military from her boarding house in Hagonoy, Bulacan while doing field work in June 2006.

Karapatan said they have documented 13 cases of enforced disappearance in the last four years. They are Honey Mae Suazo, former secretary general of Karapatan – Southern Mindanao Region, who disappeared in Davao Del Norte in 2019;Joey Torres, Bayan Muna Central Luzon peasant organizer, who disappeared in 2018;

Davis Mogul, who disappeared in Sultan Kudarat in 2016; Maki Bail, who disappeared in Sultan Kudarat in 2016;Saypudin Rascal, who disappeared in Lanao del Sur in 2017;Lora Manipis, National Democratic Front of the Philippines consultant, who disappeared in North Cotabato in 2018;

Jeruel Domingo, who disappeared in North Cotabato in 2018;Res Sr. Hangadon, who disappeared in Agusan del Norte in 2018; Deodicto Minosa of Anakpawis, who disappeared in Aurora in 2019; Argentina Madeja, who disappeared in Samar in 2019;

Jayson Calucin, who disappeared in Quezon in 2020; John Ardi Cacao who disappeared in Quezon in 2020; and Elena Tijamo of the Farmer’s Development Center – Central Visayas, who disappeared in Cebu in 2020

They join the list that includes Jonas Burgos, activist –farmer and son of press freedom crusader Jose Burgos, Jr, who has not been seen nor heard since he was abducted by what turned out to be members of the military at Ever Gotesco in Quezon City on April 28, 2007.

Cadapan said Section 29 of the Anti-Terrorism Act, which allows for the arrest and detention without charges of a terror suspect for up to 24 days “practically opens up the option for State forces to resort to enforce disappearance rather than complying with legal requirements to detain suspects. To make matters worse is that we all know torture accompanies detention. This is the stuff of our nightmares.”

It’s not only being forced to disappear from the face of the earth that has intensified under rhe Duterte administration. In many cases it’s outright murder as in the case of Randall Echanis, peasant rights advocate and peace talks consultant; human right defender Zara Alvarez, and Bayan Muna regional coordinator Jory Porquia.

“The spate of political killings follow the pattern of EJKs against suspected drug users and pushers. Like thousands of drug-related EJK victims who were included in a drug watch list, Echanis, Alvarez and Porquia werepublicly vilified and tagged by police and military authorities as ‘communists’ and ‘terrorists’ before they were murdered. Many more are under threat, including those providing assistance to poor communities during the Covid-19 pandemic,”a draft statementbeing circulated among human rights advocates said.

The statement cited a Philippine National Police report of 6,000 drug suspects killed in police operations, with the total killed in the drug war estimated to reach as high as 27,000 and counting.

“Human rights groups have reported more than 300 political killings, mostly of activists and persons tagged by agencies under the National Task Force to End Local Communist Insurgency (NTF-ELCAC) as communist rebels or sympathizers, “ the draft statement said calling “for an end to the killings and a stop to the red-tagging and vilification of activists, human rights defenders and government critics.”

The statement also demanded for “ an impartial, thorough and independent investigation of the killings of Echanis, Alvarez, Porquia, and all victims of EJKs.”

In a related development, several groups have joined the call of the Human Rights Watch for the UN Human Rights Council tolaunch an independent international investigative mechanism on the human rights situation in the Philippines.

The letter to be submitted at the 45th Regular Session of the HRC that will take place on September 14 to October 2, 2020 in Geneva, Switzerland cited the HRC resolution A/HRC/41/2 on the Philippines adopted in July 2019 which called for an independent, impartial investigation on human rights abuses following its findings of “widespread and systematic killings” in the country as“an important first step to address the concerning human rights situation in the country, but a more robust response is necessary to deter further killings and other human rights violations and ensure a measure of accountability. “

“Given the failure of the Philippine authorities to stop or effectively investigate crimes under international law and punish those responsible, we urge your delegation to work towards the adoption of a resolution to ensure that the Philippines remains on the agenda of the HRC and to create an independent, impartial, and effective investigation into extrajudicial executions in the context of the ‘war on drugs’ and other human rights violations committed since 2016. The creation of such a mechanism is the only credible next step that the HRC can take to address the ongoing human rights crisis in the Philippines,” the letter said.

(The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.)