There was an element of surprise in the June 14 announcement of former International Criminal Court prosecutor Fatou Bensouda. In her request for authorization for an investigation on Rodrigo Duterte, a scope was added. It had been understood that this was a complaint for crimes against humanity of murder committed in the context of the war on drugs, therefore beginning with the Duterte presidency on July 1, 2016.

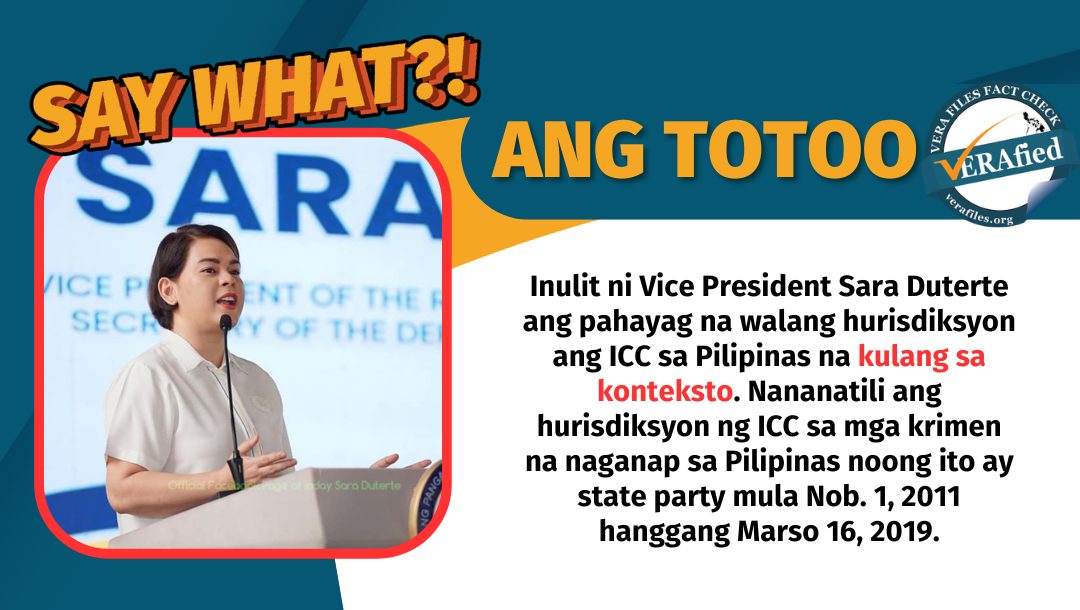

In Item No. 1 of the request’s introduction (page 3), however, Bensouda astounds: “the Prosecution hereby requests authorisation to open an investigation into the Situation in the Republic of the Philippines between 1 November 2011 and 16 March 2019.”

In the final summary of the relief requested (No. 131, page 57), she repeats the expansion of the scope: “ . . . on the basis of the supporting material submitted to the Chamber, the Prosecution requests the Chamber to authorise the commencement of an investigation. . . in relation to crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court allegedly committed . . . between 1 November 2011 and 16 March 2019 . . .” And then she concludes with a phrase that reiterates the expansion, that this is “ . . . in the context of the War on Drugs campaign, as well as any other crimes which are sufficiently linked to these events.” (highlights mine)

In 2011, Duterte was vice mayor to his daughter Sara. He became mayor again in 2013, and his vice mayor was his son Paolo. When he was elected president in 2016, there, in fact, already was international consciousness of his alleged involvement in extrajudicial killings. Reuters, for example, made allusions of the incoming president in 2016: “Human rights groups have documented at least 1,400 killings in Davao that they allege had been carried out by death squads since 1998.”

The expansion of the investigation’s scope, if it will be approved by the pre-trial chamber of the ICC, will signify only one thing: Duterte will also be tried on the basis of allegations that he had operated the Davao Death Squad when he was mayor of Davao city.

What explains Bensouda’s decision to enlarge the scope? Take note that she herself provides the answer: supporting materials. One of these could be that of the self-confessed hitman (“tirador”) of the Davao Death Squad Edgar Matobato. What Matobato did divulge about the Davao Death Squad is nothing new even to Duterte and Malacañang. On September 15, 2016, Presidential Communications secretary Martin Andanar confronted the Matobato allegations by saying the president “is not capable of giving directives like that.” Presidential spokesperson Ernesto Abella followed by saying the public should weigh the Matobato allegations with “a sense of sobriety and objectivity.”

Presidential son Paolo Duterte, also implicated by Matobato, repudiated him: “I will not dignify with an answer the accusations of a madman.”

Self-confessed member of the Davao Death Squad Edgar Matobato testifies on his role in the Davao Death Squad in September 2016. Senate photo by Albert Calvelo.

VERA Files asked for Malacañang’s side on the inclusion by Bensouda of “strikingly similar crimes” and involving an “overlap of individuals” in Davao City from 2011 to 2016.

Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque said,“There should be no truth to the allegation that outgoing ICC Prosecutor Bensouda’s request for authority to investigate the killings related to the government’s war on drugs was expanded to include the period when President Duterte was Davao City mayor. If the Prosecutor was indeed doing her job, then this ‘interview’ should not have been included or even considered because it is outside the court’s temporal jurisdiction.”

Roque further said, “We would remind the ICC Prosecutor, as well as the author of the article, that the Philippines only acceded to (and ratified) the ICC Statute on August 2011, with the Statute only entering into force in the country in November 2011. As such, the ICC has no jurisdiction over any acts prior to November 2011. The general principle of law nullem crimen sine lege therefore holds.”

In late June of 2016, Matobato decided to abandon the Witness Protection Program of the Department of the Justice. His reasons were understandably to antedate the political developments then: Duterte had just won the presidential elections and Matobato foresaw the DOJ as the wrong body that could safeguard him for his blow-by-blow revelations on the Davao Death Squad.

To signify his departure from the DOJ, Matobato personally chose a private institution to conduct an interview for his divulgement. The Matobato confession claims to be a first-person eyewitness account of Duterte’s direct involvement in extrajudicial killings that began in Davao city in 1988 and is believed to be one such supporting material that had reached Bensouda’s hands.

Matobato opens his narration: “It was Mayor Duterte himself who recruited us. He was present when we were organized during a meeting at the old Men Seng Hotel. He called us the Lambada Boys. Our work was to kill and only to kill. At the start of the Lambada Boys, actual killing served as our training, to kill people who were defenseless and who were caught unaware.”

In 1992, the name was changed to the Davao Death Squad. Duterte and the Davao city police would repeatedly deny the existence of the Davao Death Squad and even pooh-poohed the name as a “creation of media.” Before Matobato, no one had first spoken of the killing architecture of the Davao Death Squad and gave it the appearance of verisimilitude.

He narrated how the Davao city police organization and the Davao city hall had ostensibly conspired to form a killing machine that made police the criminals. “We were ghost employees of city hall, the so-called 15-30,” he said, implying that their names would not be found on any city hall payroll. “Our handlers were police. That is why no DDS hitmen were arrested because the police were also part of the DDS.”

Asked how they get a list of those to be liquidated, he revealed, “From the other personalities in the hierarchy such as barangay captains. They are also given hitmen who are rebel returnees who were not hard-core, they are the ones assigned to the barangay captains to kill small-time offenders (“pipitsugin”) and they are also 15-30 ghost employees of the Davao city hall.”

“Mayor Duterte had also issued guns to the barangay captains,” he explained.

By the time the killings had become the norm well beyond 1988, “every police station in Davao city had hitmen,” he said. Each station had civilian hitmen, police hitmen, and a supply of the homemade replica guns commonly known as “paltik.” “When there is a killing and they say there was an exchange of gunfire, those guns are planted. They are ‘paltik’ and they were reserved for planting of evidence,” he related.

So numerous were the hitmen, said Matobato, that even the National Bureau of Investigation who he had first approached when he wanted to confess, did not file anything against Duterte out of fear. “They found evidence but they were really scared. They got afraid because Duterte has a really good number of hitmen. They would have a hard time there in Davao because of that.”

Matobato describes the operation’s logistics, including the practice of reward monies for major kills. Assets of the killing machine included Hi-Ace vans, latest model vehicles like pick-ups, obviously some motorcycles, but also a big pumpboat.

“The Anti-Heinous Crime Unit of the police department was not used to arrest heinous criminals. It was part of the killing organization. The Anti-Heinous Crime department of the police had a big banca and we would use this when we were pressed for time. Instead of burying the dead body on land, we would drop it into the sea after tying it with weights,” Matobato narrated.

What can be the probable influence of the Matobato confessions? When the ICC’s pre-trial chamber (it usually takes four to six months to resolve a request for authorisation of an investigation) will rule to include the Matobato confessions, that is the time when one appreciates it as a heavyweight hitman’s confession that may have the dimension of damning evidence capable of convicting Duterte.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.