Pres. Duterte accompanied by Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana and AFP Chief- of- Staff Eduardo Año visit wounded soldiers in Camp Evangeslita Sation Hospital in Cagayan de Oro, June 2017. Malacañang photo.

If there is any institution that was able to fully institutionalize the lessons of martial law and the People Power Revolt, it is the Philippine military. That lesson is that they should always be united. They should never allow themselves to be on opposite sides of the political fence. Better be on the wrong side than to be on opposite sides. Why?

The answer is simple. When soldiers fight, they do not fight with words. They fight with bullets, rockets, and bombs. And they fight to kill and win. In the Philippine setting, a civil war military partisans on either side is unwinnable and will be like Marawi writ large.

In the end, the military will take its cue from the people. The people must decide. They must vote with their feet.

Over the medium-term, fractious the nation may be, the only stable goal that unites all Filipinos is the defense of the Constitution. Leaving the moorings of the Constitution is to be adrift in the open sea, never to find legitimate bearings.

Drifting into such contentious territory is anathema to the military. It goes against their training, their doctrine, and habits of thought and action.

While Duterte was busy making national policy through impromptu speeches all over the country, he has inadvertently slipped the balance of power in the country to the military. The military is now the only institution that stands between Filipinos and martial law.

The military seems quite comfortable holding the balance of power in the Philippines. It is secure in its understanding that doctrine dictates that the best course is to protect the Constitution. The possibility that the military will support Duterte’s narcissistic adventure into martial law or revolutionary government are slim.

Six things prevent the military from going with Duterte in uncharted territory — (1) the war on drugs that kills Filipinos wantonly, for no achievable purpose; (2) the sell-out of the West Philippine Sea territories to China; (3) the attempt to severe the Philippine military’s institutional and functional lifeline with the United States military; (4) the undeniable sentimental and historical links of Duterte to the Communist Party, National Democratic Front, and the New People’s Army; (5) Duterte’s mental instability that tends towards killing rather than healing, and the misuse of political and government institutions for narcissistic and personal ends; and (6) the military understands its limitations in operating in unfamiliar political combat territory; it will quickly dissemble if it plays a political role as backbone to a martial law regime or a revolutionary government, where personal corruption of commanders will replace loyalty to the Constitution.

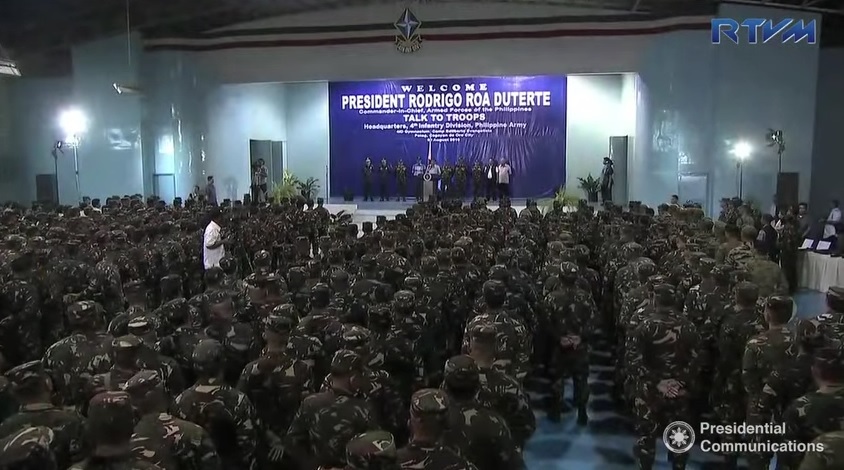

Pres. Duterte in one of his frequent visits to military camps. Malacañang photo.

What prevents the Philippines from sliding quickly into martial law or revolutionary government that makes Duterte a dictator is the institutional memory and institutional doctrines and habits of the military. Soldiers trust their lives to sergeants, lieutenants, captains, colonels, and generals. They understand the ever increasing roles and responsibilities of their officers as they move up the ladder — as soldiers who communicate, move, and kill when they are young, as managers who achieve outcomes when they are in middle rank, and as statesmen when they are of general rank.

Soldiers understand what civilians cannot — you would not want Duterte as a squad leader. You will not trust him to be a platoon leader or company battalion, or brigade commander. Heck, if you had a choice, you would not want him as a commander- in- chief. He is a loose cannon. The more fanatical his support, the more impulsive he gets, and the more dangerous he is to national security.

Towards the homestretch of the Duterte saga, it is the hypnotic trance the troll army has created in the minds of a large segment of the Filipino population that is ranged against the institutional steadfastness of the Philippine military. Every day that passes whittles down the influence of the troll army, as Duterte reveals more of his mental and verbal instability, and the army sacrifices lives to neutralize the dangers that Duterte brings to the nation.

Marawi was a turning point. Duterte was quick to declare martial law in Mindanao, thinking it was an opportune lurch towards dictatorship. To the military, it was an unnecessary, costly, and debilitating war, let loose by the tongue of one accidental President. The military sacrifices have given the military a level of political authority that is independent of Rodrigo Duterte.

In fact, the military has gained in power as against Duterte whose ability to give the military questionable and unconstitutional orders has been weakened. When Duterte and peace process chair Jess Dureza suggested that a backchannel approach to ending the Marawi siege through former Marawi mayor Solitario was broached, Lorenzana and Año virtually vetoed the idea, saying that that approach would dishonor the 150 or so soldiers who have given up their lives in the Marawi siege. I do not think any segment of the military does not identify with that sentiment.

Whatever revolutionary government Duterte is fantasizing about will have to be jumpstarted without the military, unless Duterte can appoint the equivalent of a subservient Bato dela Rosa as a chief-of-staff of the armed forces. It is too late in the day to do this. Duterte has shown how unstable his mind and hand as a leader has been. Replacing Secretary Lorenzana and General Año at this time would only hasten the spontaneous combustion of his administration.

(The author, Dr. Segundo Joaquin E. Romero, Jr. Professorial Lecturer at the Development Studies Program of the Ateneo de Manila University)