By ALLAN YVES BRIONES, PAUL JOHN DOMALAON, BRYAN EZRA GONZALES, NICOLE-ANNE LAGRIMAS and ARIANNE CHRISTIAN TAPAO

“CHILDREN with disabilities are like butterflies with a broken wing. They are just as beautiful as all others, but they need help to spread their wings.”

Maria Theresa Marquina, 41, reads the quote on the tarpaulin she is about to hang at the Special Education (SPED) center where she teaches at Nagpayong Elementary School (NES) in Pasig City.

Marquina, a grade six teacher since 2008, was assigned last year to a SPED class where her students were mostly children with cerebral palsy and intellectual disabilities.

She considers herself barely equipped to teach SPED classes but will start her second year of doing so today. Her three colleagues are all graduates in teaching SPED, one of them a master’s degree holder while she had only attended several sign-language and sensitivity seminars prior to her first stint.

As classes in thousands of schools nationwide resume today, Marquina and many other teachers face yet again the many challenges of managing SPED classes, carrying the burden of not just instilling knowledge on their students with disabilities but also ensuring their safety while in class.

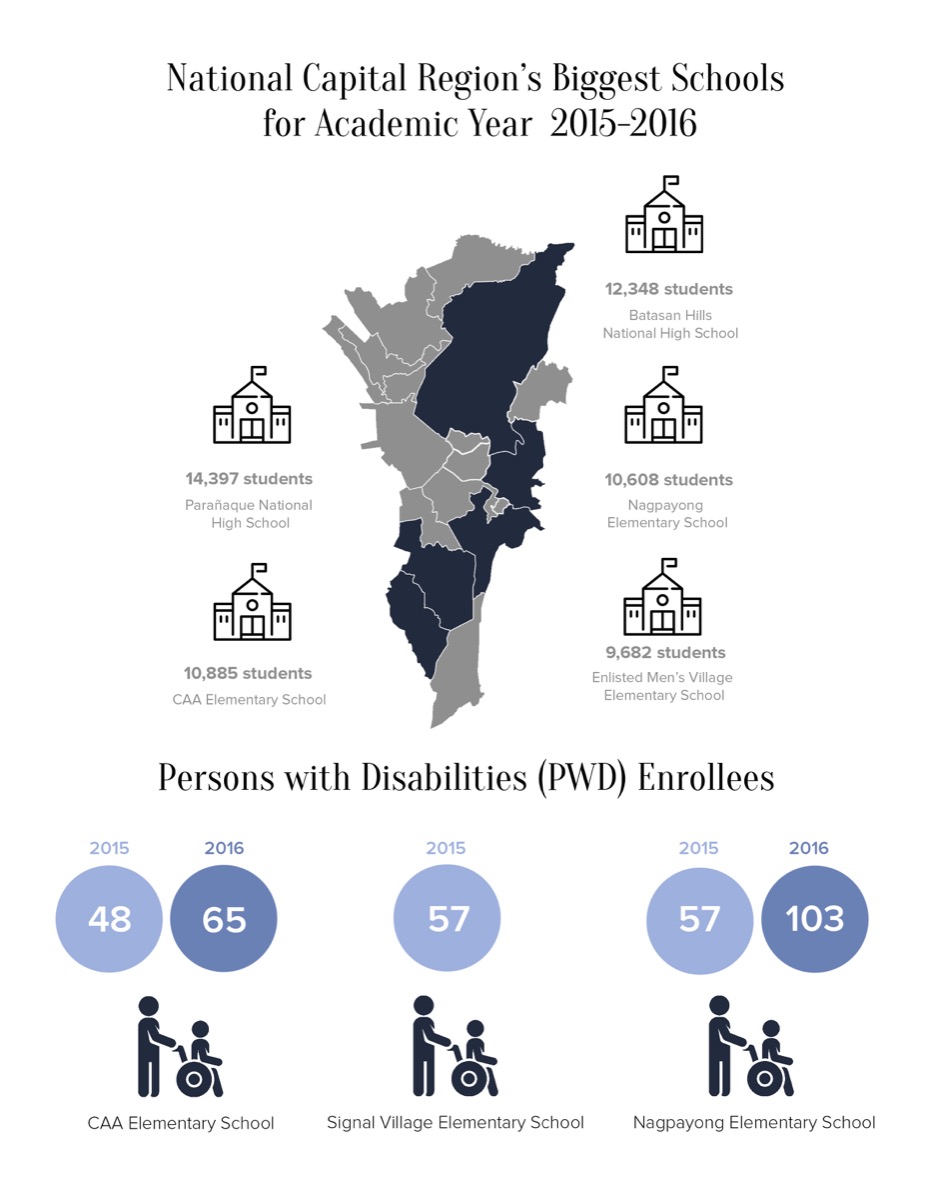

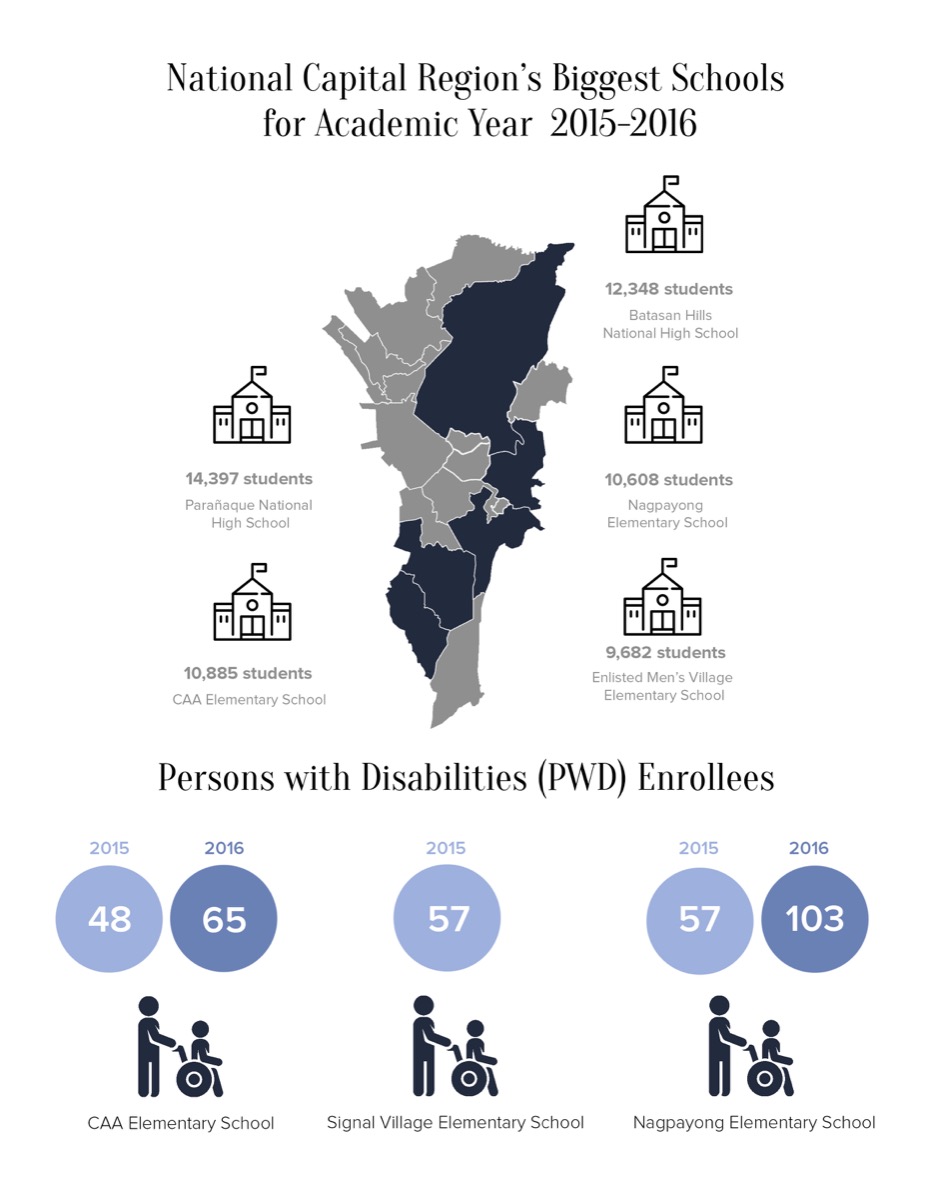

A closer look at the five largest schools in Metro Manila in terms of student population shows they still lack trained teachers, proper facilities and equipment while the number of students with special needs continues to grow. (See Most schools used as voting precincts not PWD-friendly, audit shows)

Nationwide, the number of SPED enrollees rose by 13.04 percent from 38,671 in 2014 to 43,712 a year after, according to recent data from the Department of Education (DepEd).

In the National Capital Region alone, there were more than 8,000 SPED students at the elementary level and around 320 at the secondary level last year.

NES, which opened its first SPED classes in 2014, is still lacking in resources such as hearing aids and sign language books for students with hearing disabilities and materials in Braille for students with visual disabilities, said Lalaine Batisla-Ong, another SPED teacher. (See From handmade Braille teaching aids to rooms on the second floor at Manila’s biggest SPED school)

“Minsan, naghahanap na ng sponsors ‘yung mga estudyante (Sometimes, the students start looking for sponsors),” she added.

NES handled a total of 103 SPED students with cerebral palsy, intellectual, visual and hearing disabilities last year. This year, the school is expecting around 90 SPED enrollees for its Level 2 SPED program.

This is probably one of the reasons teachers like Marquina are being assigned to teach SPED classes despite not having the adequate training to do so.

Aside from this, the school has yet to construct a new cubicle for the center in addition to the four existing cubicles for students with disabilities.

The lack of SPED rooms is a problem not only in NES, but also in a number of other schools in Metro Manila. CAA Elementary School in Las Piñas, which according to DepEd has the largest number of elementary students nationwide, had 48 students registered under SPED last year.

This school year, the number rose to 65, and they have to be crammed in one classroom.

“Nahihirapan kami mag-schedule kasi 65 SPED pupils po then one classroom…so all po nang nag-eenroll, ma-cater po namin (We find it hard to schedule 65 SPED pupils in one classroom which we need to do to cater to all enrollees),” Krisha Elequin, a CAA SPED teacher, said.

According to Elequin, the school has three SPED teachers but still fails to satisfy the ratio of one teacher for every 10 students. As of the incoming school year, the number is at 11:1.

Rooms are not as conducive as Elequin hopes to be, either. She said they requested for a well-ventilated, well-lit and a generally conducive environment for SPED students, as “they are easily distracted,” particularly those with intellectual disabilities (ID).

Furthermore, the ongoing construction project right outside the classroom is seen as a potential danger. Noise from falling debris, electric saws and jackhammers can all too easily induce seizures in her students with cerebral palsy, Elequin said, narrating a past experience.

“Isang beses sa gitna ng klase, inatake (ng seizure) yung isa sa mga bata (One of my students had a seizure in the middle of a class),” she said.

“Siguro sa sobrang ingay or sa sobrang init, kaya nagre-request ako ngayon ng nurse para sa classroom (Maybe because of the heat or the noise, so I’m requesting a nurse for the classroom),” she added.

The child recovered after a few minutes, Elequin said, but that was an extremely close call. Currently, the school only has one nurse for all of 10,885 students enrolled last year. With the increasing number of SPED enrollees this year, Elequin is worried that one nurse won’t be able to respond to a similar emergency.

To be fair, the school has managed to assign the SPED classroom to the ground floor and has provided ramps, signage and an exclusive bathroom for greater accessibility for PWD students.

Closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras and fire alarms are also available to guarantee the safety of the students.

Meanwhile, the biggest high school in Metro Manila, home to more than 14,000 students as of last year, suffers from a shortage of teachers as well.

Equipped as it is with an existing SPED program, Parañaque National High School (PNHS) still finds itself lacking in teacher-interpreters, or teachers who use sign language to relay lessons to students with hearing disabilities.

The school has only four teacher-interpreters, one per each level, said Annie Mascariñas, the SPED coordinator of PNHS. For a school with more or less 50 enrollees in the SPED program, this figure is far from the ideal two-to-one teacher-interpreter to classroom ratio, she said.

Mascariñas acknowledges the reason for the shortage: “The problem is we do not have an item (job position) for SPED teachers in high school.”

They have asked their higher-ups why this is so, she said, but got told: “Nasa region (DepEd) na yun (It’s in the hands of the regional office).”

This is also the reason the three incoming senior high school students of PNHS, graduates of the SPED program, are left without teacher-interpreters exclusive to their senior classes. DepEd guidelines are in the works, Mascariñas said, but in the meantime, these three remain under the care of their junior high school teacher-interpreters, whose schedules are tight to begin with.

For a teacher-interpreter at PNHS, a work day begins with staying with the SPED students during class time and extends until after official school hours, when they would hold tutorial sessions with their students.

And for no extra compensation other than allowance, too, said Mascariñas, the job being a “sacrifice,” a “labor of love.”

“Hindi pwede sa SPED ang eight-hour person (An eight-hour person won’t do in SPED),” she added.

The school’s SPED program is “mainstreamed,” which means SPED students are included in a “regular” section and are accompanied by a teacher-interpreter, said Mascariñas. Teacher-interpreters teach lessons to the mostly deaf or hard of hearing SPED students right alongside the regular class’ teacher through sign language.

As of now, their catch-all solution for the lack of teacher-interpreters in both junior and senior high school is to orient the regular teachers of the condition of some of their students so they can manage their classes better.

For Mascariñas, however, the best solution would be an increase in teacher-interpreters for their students, which they can only hope for at present.

Where PNHS has four, one of the biggest elementary schools in the region has only one person to fill the need for teachers for students with special needs.

Her name is Bernandita Edjec, and it is her first time handling a SPED class where she is expecting as many as 60 pupils.

Edjec recently finished her doctorate on Special Education and is teaching at Enlisted Men’s Signal Village Elementary School (EMSVES) in Taguig City, where 35 SPED students have enrolled as of June 10.

“I am praying na wag naman sana umabot [ng 60], mahirap tumanggi, pero kung sana mag-transfer na lang sila sa ibang schools, mas maganda yung ma-acquire na learnings nila [dun] (I am praying the number doesn’t reach 60; it’s hard to deny (enrollees), but they might acquire better learning if they transfer to other schools),” she said.

Even for DepEd Taguig-Pateros’ only recognized Center for Special Education, EMSVES lacks regular positions for trained instructors. Other than Edjec, only two volunteer aids and one other non-item volunteer teacher help run the morning sessions both for the newcomers and advanced classes.

Edjec said there should be at least three teachers handling the daily sessions, especially since they are teaching children aged 5 to 17, with different conditions such as autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, learning disabilities and intellectual disabilities.

And though it wasn’t in her plans to be a SPED teacher, her specialization being educational management, she said she finds happiness in the job.

“Hindi naman ito yung patience na meron ako, pero naisip ko pag nagkikita ko sila, agad-agad namang sumasaya rin ako (I don’t have this kind of patience [needed for teaching SPED students], but when I see them I instantly become happy),” Edjec said.

In the absence of SPED classes, meanwhile, another school has a substitute program.

Up north, the Batasan Hills National High School (BHNHS) in Quezon City, which serves the second largest number of enrollees at the secondary level, admits its students with disabilities under the alternative delivery modes (ADM), a special program pioneered in 2000 in the absence of SPED classes.

Unlike under the SPED program, where special classes are reserved for students with disabilities, PWDs under the ADM are mixed with out-of-school youth, indigent enrollees, overaged and pregnant students. (See Early enrollment for children with disabilities under way)

Formerly called the home study program, classes under the ADM are only held every Saturday. During these sessions, each student is given school work per subject for each day of the week. Students are expected to submit all these requirements the following Saturday. (See Homeschooling children with disabilities)

Assistant principal Cerilo Castillo said the ADM program was also implemented largely due to the lack of classrooms in previous years.

Given the lack of accessible ramps in the campus, he said, the school assigns students with mobility problems to classrooms on the ground floor.

“Actually napag-iwanan na nga lang tayo dito sa Pilipinas (Actually, the Philippines has been left behind),” he said. “Yung mga progressive countries ito [ADM] na ‘yung ginagamit (In progressive countries, they are already implementing the ADM),” Castillo said.

The assistant principal said the school does not categorize its ADM students, thus the absence of a separate documentation for students with disabilities.

Arnold de Guzman, head of Quezon City’s Persons with Disability Affairs Office, said while the program is commendable for addressing the school’s backlog of classrooms, actually mainstreaming PWDs, where students with disabilities get integrated in regular classes, would have been a better practice.

“‘Yung [pag]-isolate, discrimination na ‘yun e (Isolating them is already discrimination),” De Guzman said, referring to PWDs being admitted in the ADM program.

However, Castillo said PWDs are already in a community and the program prevents them from feeling “na para bang pinandidirihan mo (that they disgust you).”

He agreed that the long-term goal has always been for them to feel the public acceptance—to feel that they are normal. “Kasi ganun din naman sa community ‘di ba? Halo-halo tayo (Because isn’t that what our community is? We’re all mixed together).”

The five largest schools in Metro Manila will continue to accommodate students with disabilities. Despite all the issues they face, hope is far from lost, it seems, especially for teachers like Elequin and Marquina.

Back in Nagpayong, the school will be kicking off the year on a hopeful note as it plans to finally integrate one student with visual disability to regular classes.

Just three days before classes start, too, two other teachers fix the center’s dilapidated ceilings. Marquina, meanwhile, was busy decorating the SPED center, hanging sign-language charts and inspirational quotes on its green walls.

But she does not stop there, still. Although Marquina’s students are mostly students with learning disabilities, she takes her job a notch higher by frequenting YouTube videos for sign-language tutorials, she said, to help her communicate with her students better.

“‘Pag nakikita mong nagbabago sila, may natututunan sila, kahit na mahirap silang turuan, okay lang (When you see them learn, even if it’s hard to teach them, it’s worth it),” said Marquina.

Marquina said she has learned to love these children, and through them, she has finally found her calling: to help them spread their wings, as the quote says.

(The authors are University of the Philippines students writing for VERA Files as part of their internship. The data sets used in this report were provided by the Department of Education to the university under the “Data and Society: Applications in Public Education” program supported by the UP Emerging Interdisciplinary Research Program.)