“I did what I had to do,” former president Rodrigo Duterte said in his opening statement before the Oct. 28 Senate Blue Ribbon subcommittee hearing on the battle against illegal drugs under his watch.

“The war on illegal drugs is not about killing people. It is about protecting the innocent and the defenseless,” the former chief executive said.

Unrepentant, Duterte offered no apologies or excuses because, in his own words, he did it all for the country.

Over 6,200 were killed in drug war operations by the end of his term in 2022, according to Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency data. But the Commission on Human Rights estimates the deaths to have reached as many as 27,000 by December 2018.

Following the admission of a few police officials that they received monetary reward for some of these killings, the House quad committee vowed to pursue justice for the “countless” families who lost their loved ones in the campaign.

The quad committee – composed of the Committees on Dangerous Drugs, Public Order and Safety, Human Rights and Public Accounts – is investigating possible links across offshore gaming operators, illegal drugs and extrajudicial killings in the past administration.

By the end of October this year, a Senate Blue Ribbon subcommittee launched a separate probe into the matter.

As lawmakers questioned Duterte and his allies during hearings, VERA Files Fact Check flagged statements that appear to whitewash the troubling impact of the drug war.

Here are the emerging patterns:

Damn the ‘guilty’ to hell

Duterte and his allies resorted to four strategies: the assumption of guilt of drug suspects, distinction between drug addicts and peddlers, emotionalization and disinformation.

Rhetoric uses language to “influence the audience in a given direction.” Politicians use rhetorical strategies to gain support for their vision, as suggested in a 2014 study on social identities and communication tactics. In this way, they paint an identity of themselves or of a certain group for their audience.

While due process guarantees the presumption of innocence, the narrative of the war on drugs immediately labeled as criminals anyone suspected to be involved in drugs. Of the 11 statements flagged by VERA Files Fact Check, four assumed the guilt of those killed in drug war operations.

This maintained a dehumanizing narrative that Duterte prominently used when he was chief executive, based on a 2023 masters thesis from Utrecht University analyzing the former administration’s drug war rhetoric from 2016 to 2017.

Dehumanizing narratives endorse the harsher treatment and punishment of certain groups of offenders, based on recent studies.

Such a narrative was also evident when opposition Sen. Risa Hontiveros asked Duterte during a Senate hearing if he thought drug addicts and drug criminals “deserved” to die. Duterte replied in Filipino: “Why would I [spend to] keep alive those sons of b*****s when I could spend that money for people without rice, without jobs?”

“I don’t care about those criminals. I don’t care about wherever hell these criminals want to go,” Duterte added.

Orville Tatcho, associate professor of speech communication at the University of the Philippines Baguio, said such narratives undermine the presumption of innocence that is enshrined in the Constitution.

“‘Yung presumption of innocence…‘yun ‘yung nawawala dito. Kasi pagka sinabi lang na, ‘Uy, may adik sa ganitong barangay!’ Sinabi no’ng kapitbahay niya, ganun kasi ‘yung tokhang. Parang community surveillance din siya in a way kasi nare-report ng mga ka-barangay ‘yung mga pinaghihinalaan nilang adik,” explained Tatcho.

Portray police as peacekeepers

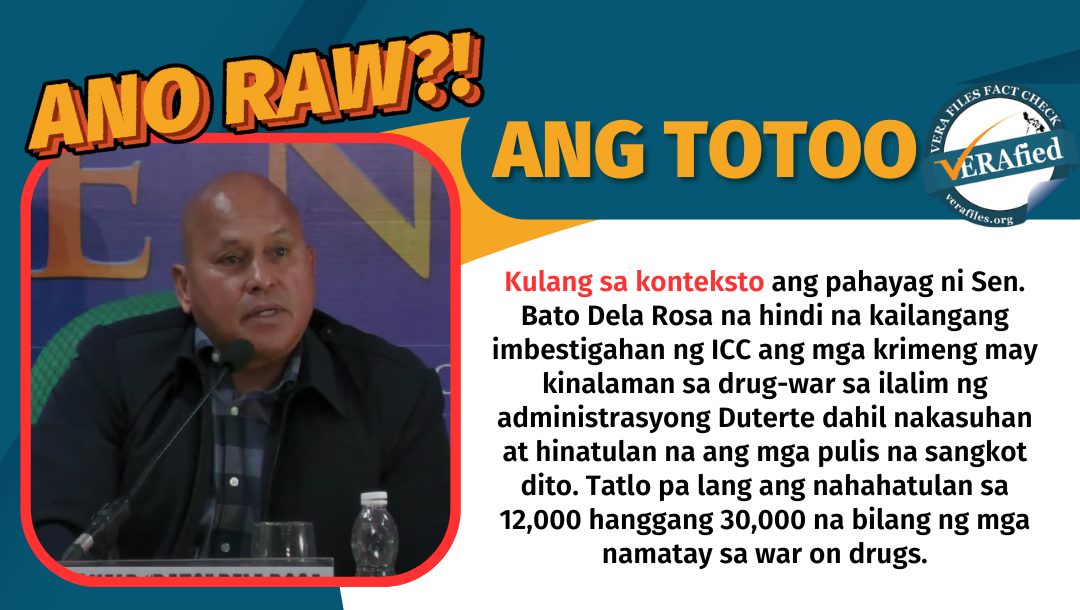

Duterte, Sen. Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa and Sen. Christopher Lawrence “Bong” Go spoke in harmony to prop up the image of the police despite statements from retired police colonel Royina Garma that they received incentives to kill suspected drug personalities such as pushers and users.

Duterte and Dela Rosa portrayed the police as peacekeepers who deserve to be revered for addressing the “pervasive” drug problem and other crimes that stem from it. Go painted the police as figures to be pitied, as lawmakers question them for their “sacrifice” as “heroes” in the drug war.

On the other hand, Duterte and his allies called suspected drug personalities “addicts,” “pushers,” “users” and even “criminals.” The use of these words attempt to evoke fear of those labeled as such. This is called the strategy of emotionalization or the “intentional invoking” of emotion within an audience.

In a 2018 analysis of rhetoric of then-sitting presidents Duterte and Donald Trump, media, politics and communications expert Dr. Anna Szilágyi wrote: “In the political realm, such metaphors encourage people to see their fellow human beings who belong to a particular group as obnoxious, disease-carrying, and/or bloodthirsty creatures that should be removed or isolated from the community.”

While Duterte did not deny the role of the police in implementing the drug war, he and his allies resorted to downplaying the role of the police in the death of victims through statements that either removed their accountability or minimized the impact of impunity.

This depiction of the police as peacekeepers, although they have been given the go signal to resort to violence to control crimes, is a “smoke screen” that attempts to mask the fact that the police had served as “an able and willing killing machine” for the drug war, explained Tatcho.

Deprioritize the truth

Some academics scrutinize the Duterte presidency and his war on drugs through the lens of post-truth—an approach that also explains why the information sphere is the way it is. Tatcho explained that post-truth describes an information sphere where facts come second to emotional appeal.

Duterte anchored his war on drugs not on facts and numbers but on dehumanizing drug users and instilling fear. Duterte’s narrative of drug suspects as “irredeemable” and a “menace to society” effectively taps into people’s desires for safety, order and security.

However, from portraying drug users in the same light as drug pushers and drug lords, Duterte’s appearance in the House and Senate probes showed a shift to the rhetoric of rehabilitation for users’ addiction. Nonetheless, Duterte’s exaggeration of the drug problem persists from when he was president up to the recent congressional probes on his anti-drug campaign, said Tatcho.

When zooming in on the political discourse at the emergence of post-truth, Tatcho suggested looking beyond the numbers. Although facts are vital, “Let us not dismiss the role of emotion in political discourse kasi they orient us to certain issues,” he said.

Consider using emotional appeals in combatting disinformation, Tatcho said. He urged that journalists use “humanizing rhetoric” in drug-war stories to revive the human from the corpse of Duterte’s caricature of drug suspects.

When personalities like Duterte use rhetoric to spread disinformation and engage in political theater, Tatcho said the challenge to journalists is to decide if their words still deserve a platform. He asked, “Bibigyan mo pa ba talaga ng airtime? (Will you really still give him airtime?)”—or in the case of the audience, clicks, shares and likes.

It is said that even the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Perhaps, the way back is striking a balance between logic and emotions, as Tatcho suggested, and adapting a frame of mind that focuses on one thing: “How do we give justice to the victims?”