MJ Bobis and Charm Ison were both classified as females when they were born. But growing up, they felt something was different about them.

At 23, Bobis sought medical help for pain in his groin. He underwent an ultrasound on the recommendation of his gynecologist, who traced the pain to an undescended testicle – which was later removed through surgery.

A 34-year-old city government employee, Ison noticed he was developing secondary male characteristics at puberty. But no one around him could explain what was happening to his body.

Both soon learned they were intersex, a medical umbrella term for people born with variations in sexual characteristics that do not fit the binary categories of female and male.

In a forum organized by Intersex Philippines last Oct. 21, endocrinologist Lizette Lopez clarified that intersexuality is not a “disorder, disease or condition.” While an estimated 2% of the global population is intersex, there is a severe lack of data on them in the Philippines.

“[Intersex] is a normal variation in animals, and it’s a normal variation in humans. We just don’t recognize it as such,” Lopez emphasized, adding, “Intersex is natural. It is not abnormal.”

After consulting with a doctor, Ison was diagnosed with hermaphroditism because of his genitalia that don’t look typically male or female. This is not always the case for all intersex people, however. It is just one of the over 40 intersex variations that are based on a person’s sex characteristics – like chromosomes, hormones, genitalia and internal reproductive organs.

In the forum, Lopez explained that “hermaphrodite” is an outdated and often stigmatizing term to describe intersex individuals because it suggests a person has fully developed male and female reproductive organs, which is biologically impossible.

Bobis, a 28-year-old health worker, was diagnosed with another intersex variation called partial androgen insensitivity syndrome, a genetic condition where the body cannot respond to male sex hormones or androgen.

“Kung meron na agad sanang data sa healthcare, hindi na sana lumala pa [ang complications ko]. Kasi ‘yung mga doktor e hindi nila alam kung ano sakit ko nung una. (If only there was data already available, my complications wouldn’t have worsened. Because even the doctors didn’t know what I had at first),” Bobis shared at the forum.

Funded by the Canadian embassy through the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives, the Intersex Rights Forum is the first-ever event that allowed the community to work together in identifying solutions to advance their rights.

Ison, who was also present in the forum, said awareness of their condition, especially among parents, could have prevented discrimination against people like him.

“We have always existed. But for many of us, we have lived in silence, misunderstood, judged, or even harmed because of who we are,” Jeff Cagandahan, executive director of Intersex Philippines, said. “Ipinanganak kaming ganito, hindi naman namin piniling maging intersex (We were born like this. We didn’t choose to be intersex).”

Discrimination fueled by ignorance

On social media platforms, specifically in the feedback section of posts about intersex rights, Cagandahan often sees comments even blaming people like him for the natural hazards hitting the country. They say that the mere existence of intersex people is causing society’s downfall.

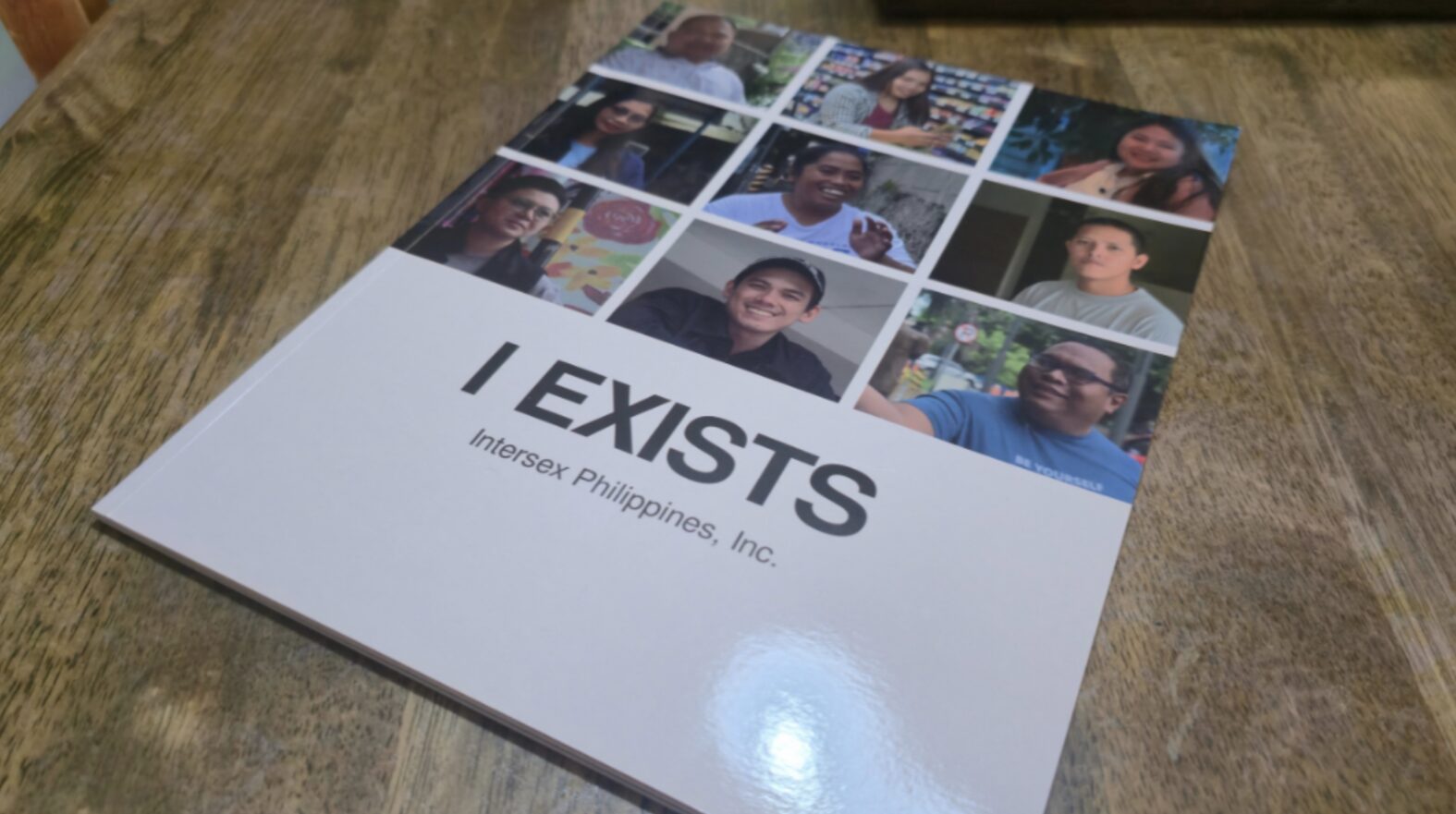

In a series of anecdotes compiled by Intersex Philippines in a handbook entitled “I Exists,” Bobis said people who do not understand what intersex is often assume he is a lesbian.

“Naranasan ko sa [paghahanap ng] work, hindi ako natanggap. Kasi imbes na skills ‘yung pag-usapan, ang nangyari, magugulat sila, [kasi] parang bawal doon ang lesbian. Ang tinatanggap lang nila male or female,” he said.

(I experienced getting rejected for a job I applied for because instead of focusing on my skills, they got overwhelmed because it was like lesbians were not allowed in their workplace. They only accept male or female.)

In school sports events, Ison was not allowed to join the men’s team and was forced to play with the women.

“Dumating sa point na ayaw ko na makipaglaro kasi hindi ko alam kung para saan ako. Kahit pangarap kong maging basketbolista,” he shared.

(It came to a point where I lost interest in playing because I didn’t know where I fit. Even if I dreamed of being a basketball player.)

These are just some of the instances of discrimination intersex people in the country face. To humanize the intersex rights movement and put a face to the advocacy, Intersex Philippines produced a short documentary with the title, “I Exist.”

Featuring anecdotes of the abuse intersex people have to deal with after they are outed, the documentary premiered during the forum.

Inaccessible medication

Aside from the abuse and discrimination, Intersex Filipinos face another challenge: lack of access to affordable medicine. So much so that Jhen Ferrer, mother of an intersex child, has had to work several jobs to buy prescription drugs for three-year-old Hero – and still make ends meet for the family.

Hero was diagnosed with salt-wasting congenital adrenal hyperplasia, an intersex variation where the body produces too much androgen but too little cortisol, another hormone which helps the body respond to stress, and aldosterone to regulate salt levels in the blood.

Hero’s condition is considered life-threatening. Without maintenance medicine, an adrenal crisis may be brought on by these hormonal imbalances, where the toddler becomes significantly weak with a fever that takes a long time to break.

“Buhay ng anak namin ang gamot. Kung wala ‘yun, maaaring mawala sila sa’min (Medicine is our children’s lifeline. If there’s no medicine, we may lose them),” Ferrer lamented.

But the medication sets back Ferrer’s family by P7,000 a month. This excludes quarterly laboratory expenses, which may run up to P10,000.

On top of the cost, access to these drugs presents a huge problem since only one pharmaceutical company based in Metro Manila carries the medication, Cagandahan noted.

“Another problem now is accessibility for those residing in the Visayas and Mindanao. Because the company does not have competition, the medicine becomes inaccessible,” Cagandahan said in Filipino.

Intersex people may avail themselves of financial aid from the government, like the social welfare assistance programs of the Department of Social Welfare and Development.

“But the fund is all-encompassing, meaning it’s for everyone,” DSWD Undersecretary Elen Pasion said during her session in the forum. “It does not take into account that there are intersex people who need programs directly related to their concerns.”

Because of this, Cagandahan and his organization hope to have a dialogue with the Department of Health to include the medicinal needs specifically of intersex people in PhilHealth’s universal healthcare package.

“Sana huwag niyo na kami pahirapan… Naghihintay pa kami ng buwan bago kami bigyan. Kung tutuusin ‘yung hinihingi namin is napakaliit lang,” Ferrer said.

(Please don’t make it difficult for us… We need to wait for months before we receive financial assistance. If you think about it, we’re only asking for a meager amount.)

Lobbying for legal inclusivity

Intersex characteristics may show up at birth, during childhood or later in life, or never. Since these traits are not always evident at birth, some intersex people’s lived identities may not match their assigned sex at birth.

This is the case with Cagandahan – formerly Jennifer – who was assigned female at birth but whose genitalia does not match that of a female. He tried to have his gender marker and legal name changed in his birth record, bringing the fight all the way to the Supreme Court.

The High Court affirmed his petition in 2008, setting a legal precedent that recognizes the right of intersex individuals to change their gender markers according to their lived identities as supported by medical evidence.

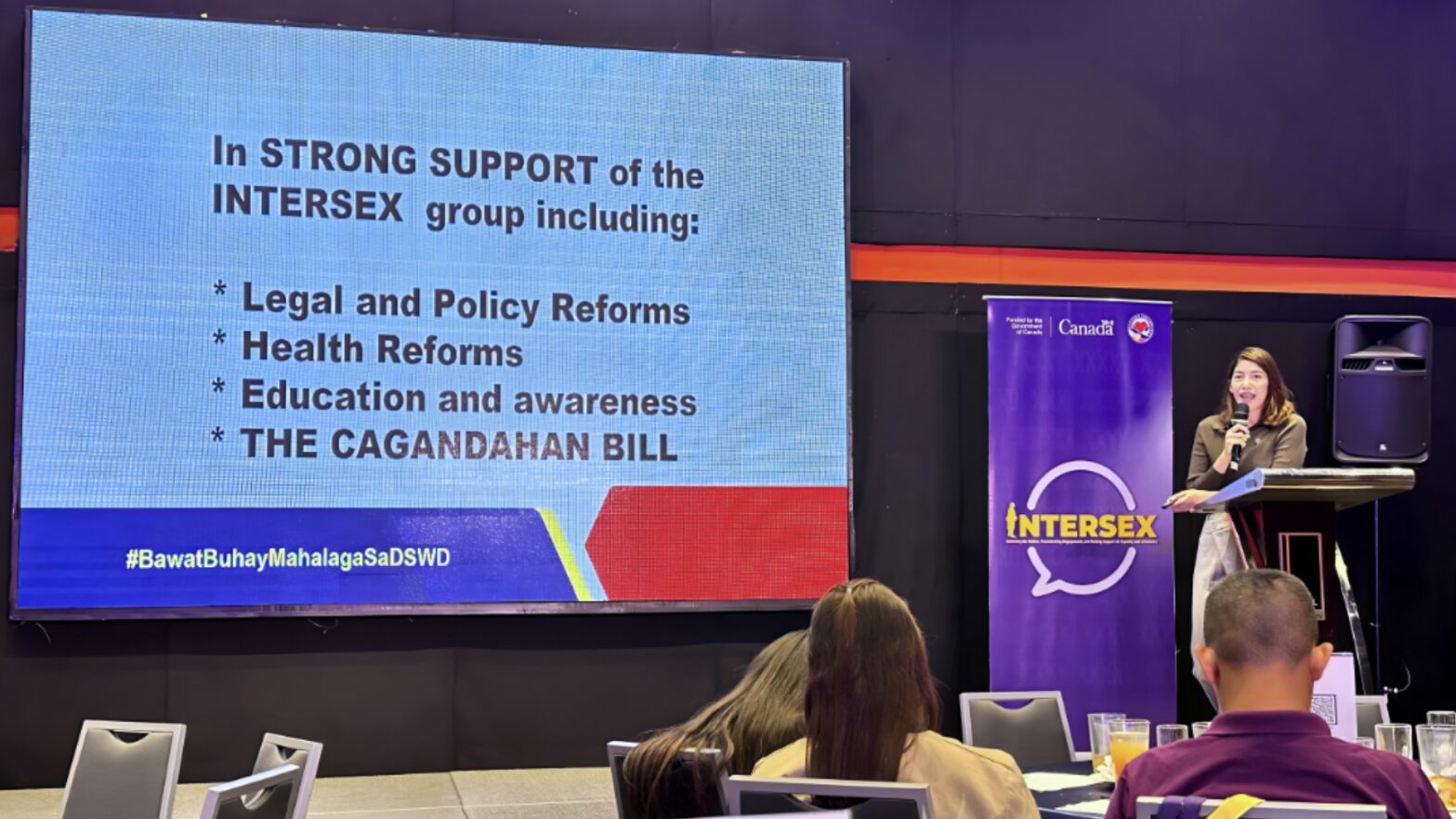

Despite this landmark decision, intersex people still need to go through tedious and costly court procedures to make changes to their birth records. This prompted the filing of the Cagandahan Bill, which seeks to simplify the process.

The proposed legislation allows intersex individuals of legal age to file a verified petition before the local civil registrar, supported by a medical certificate from a licensed physician confirming the presence of intersex traits.

The bill failed to pass in the 19th Congress but has been refiled by lawmakers Antonino Roman III and Perci Cendaña in the House of Representatives.

“We need a law because if there is no law, there is no basis for various policies. Even if ordinances are passed, they can still be questioned at the LGU level,” former Bataan district representative Geraldine Roman said in a mix of English and Filipino. “We need a national law that will attend [to] and address [the] main concern of the intersex community.”

Atty. Krissi Twyla Rubin, officer-in-charge of the Commission on Human Rights’ Gender Equality and Women’s Human Rights Center, said the lack of legislation or policy makes data gathering on intersex people virtually impossible as no budget is allotted for such an endeavor.

Despite this, Rubin emphasized that constantly engaging with government agencies remains important in pushing for intersex inclusion to encourage advocates within the system.

Although the Cagandahan bill received support from the DSWD special committee for LGBTQIA+ affairs, Pasion acknowledged it will be an uphill battle before the proposal becomes law.

“I do not want to promise that this will happen soon, but at the very least, for us policymakers, this is what we should prioritize,” she said.

Roman, a transgender woman, echoed a similar sentiment, encouraging the intersex community to remain visible despite the expected long waiting game.

“What we need is a national campaign to drum up support for our cause… It is a numbers game. The more congressmen you convince, the more chances of winning. Drum up support. Let your stories be heard,” she urged.

For Cagandahan and the intersex community, the fight for inclusivity does not stop just because the ball is already in Congress. From hosting a forum and information caravans to reaching out to people within and outside their community, intersex people affirm their place in society with their battle cry, “I exist.”

Intersex Philippines Executive Director Jeff Cagandahan discusses the organization’s efforts to advance intersex rights and inclusion. VIDEO: Rhoanne De Guzman

They invite the public to join them in spreading awareness about their struggles and fighting misconceptions about intersex so they don’t remain on the fringes of society.

“Patuloy akong nagsasalita. Nagpupunta sa iba’t-ibang bansa, iba’t ibang parte ng Pilipinas (I continue to reach out to people from different countries and different parts of the Philippines) because we want to educate the public [about] intersex,” Cagandahan said.

For the intersex community, Oct. 21 was just the beginning of claiming their collective voice and rightful place in society as they make the public understand that they matter – because they exist.