First of two parts

Rex Magbanua was 7 years old when he first joined his father to fish in the waters of Bago City in Negros Occidental. Like most kids, he was amazed to see a handful of fishes caught using their long nylon ropes.

Another scene he vividly remembers was the sight of dolphins swimming with them every time they went out to the sea. Those were different from the pictures of typical dolphins in grade school textbooks. What Rex saw had rounded foreheads and did not have snouts.

“Since sumama ako sa pangisda, nakakita na ako niyan always kasi sumasabay sa amin ‘yan… Ikaw na lang siguro ‘yung magsasawa sa kakatingin kasi araw-araw mo ‘yan makikita,” he recalls in an interview on Sept. 30.

(Since I joined [my father] in fishing, I was already seeing dolphins because they usually swam with us. You’d have more than enough looking at them because you see them everyday.)

Now 39 years old, Rex eventually discovered that what he was seeing since his childhood were called Irrawaddy dolphins (scientific name: orcaella brevirostris). When he joined Bago City’s environment management office in 2015, he learned that the marine mammal’s population has dwindled over the years.

Scientists and environmental groups are wary that the few remaining Irrawaddy dolphins in the area face total extinction with the looming construction of the 32.47-kilometer Panay-Guimaras-Negros (PGN) Bridge.

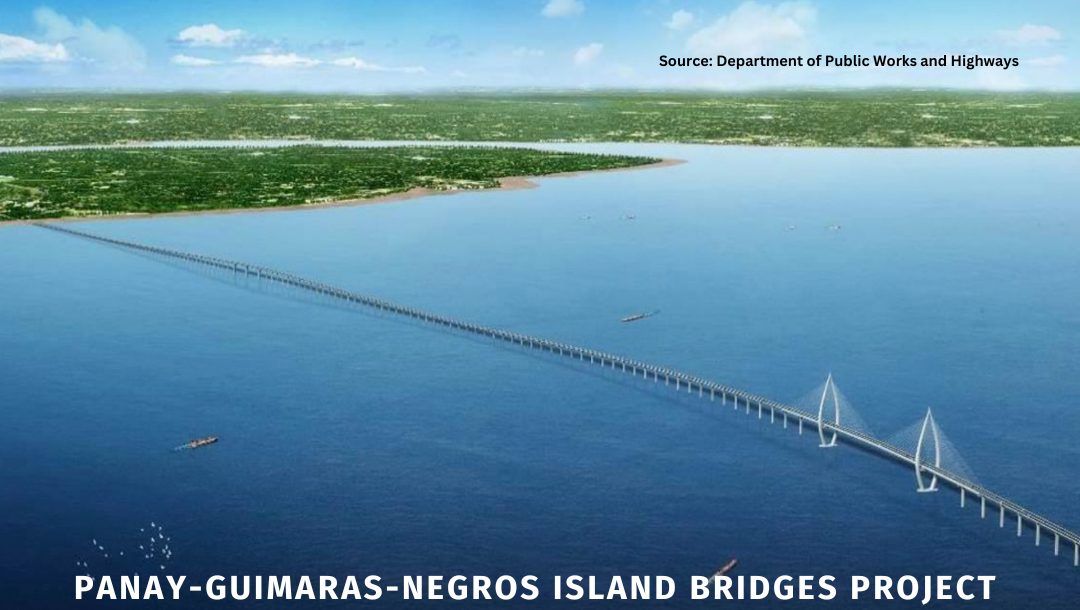

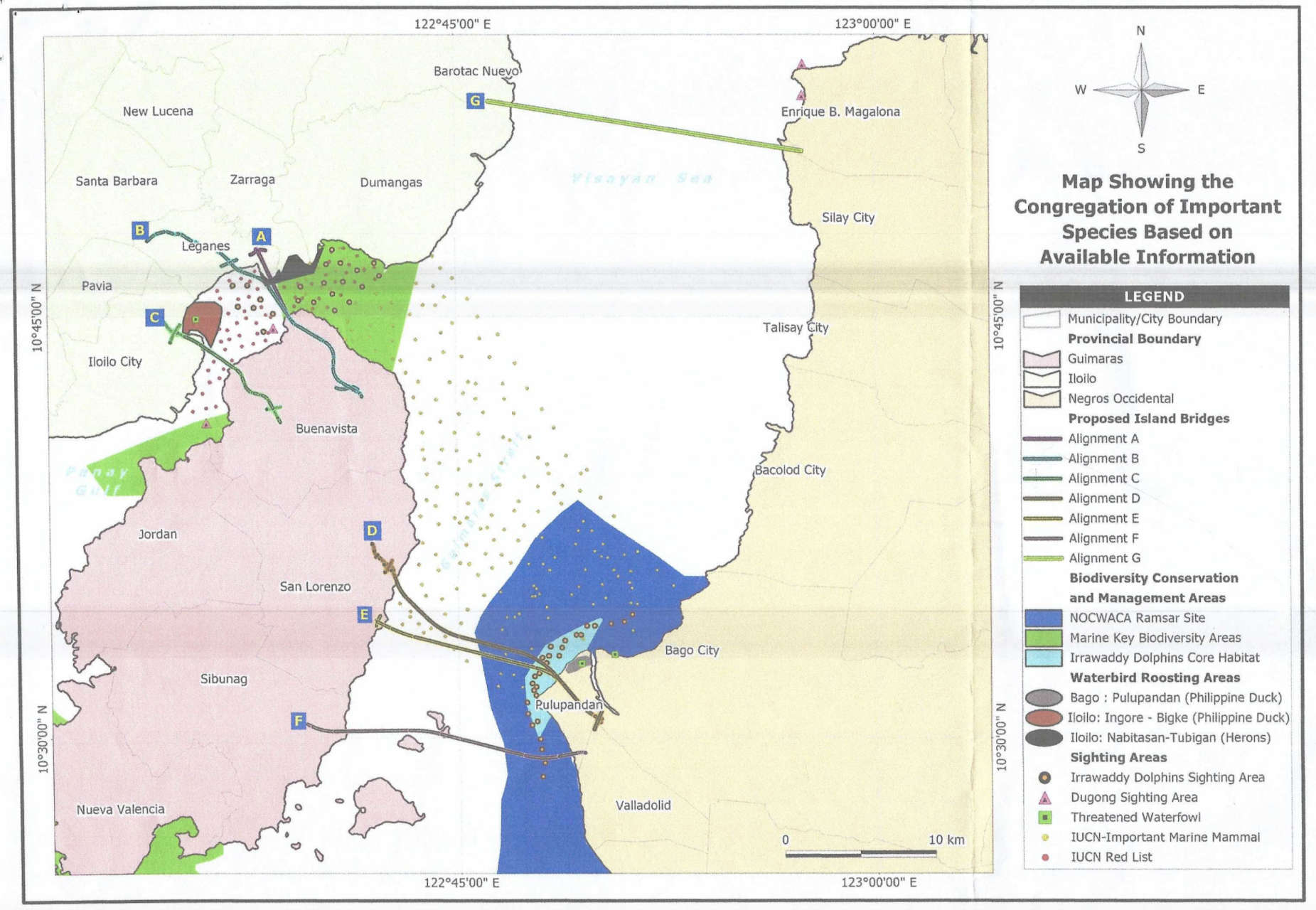

Primarily financed through foreign grants and loans, initially from China and now South Korea, the P187.54-billion mega-bridge is expected to ease travel and boost economic activity as it connects three islands in Western Visayas. It involves the construction of two sea-crossing bridges: one that would link Leganes, Iloilo to Buenavista, Guimaras and another that would connect San Lorenzo, Guimaras to Pulupandan, Negros Occidental.

Of these two bridges, the Guimaras-Negros section is feared to directly hit and destroy the core habitat of the Irrawaddy dolphins along the estuarine waters of Bago City and Pulupandan.

“[It is] the feeding ground, socialization ground and also calving [and] mating grounds so that habitat is very critical to the existence of the Irrawaddy dolphins there… So, it’s just unfortunate that these are also the areas where the exits and entrances of the bridges are located,” explained Dr. Louella Dolar, an independent marine biologist from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and professor at Silliman University, during an Aug. 7 interview with VERA Files.

Critically endangered

While fisherfolk like Rex have been seeing the Irrawaddy dolphins, or what locals call lumba-lumba, for decades now, Dolar said it was only in 2005 that their presence in the Iloilo-Guimaras Straits was confirmed.

This dolphin subpopulation was the second to be discovered in the country, following one from the Malampaya Sound, a protected inlet of the South China Sea on the northwestern coast of Palawan, in 1986. Two more subpopulations were later reported in Quezon, Palawan and in San Miguel Bay in the Bicol region in 2013 and 2023, respectively.

Irrawaddy dolphins are species that thrive in brackish waters found in estuaries, or areas where rivers and seas meet. They could grow as long as 7.5 to 9 feet and weigh from 90 to 200 kilograms. As marine mammals, their vision is blurry underwater, so they rely on their hearing for navigation in a process known as echolocation.

This dolphin species is “found only in the tropical and subtropical Indo-Pacific region,” mostly in Myanmar, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Thailand.

Dolar has been conducting studies since 2010 on the Irrawaddy subpopulation in the Iloilo-Guimaras Straits. In a 2014 survey with her team from Silliman University, Dolar found between 18 and 23 dolphins in the area. That number has further decreased, according to their 2016 survey, which documented only nine to 19 individuals.

Studies attribute this Irrawaddy dolphin’s population depletion to multiple factors, including their accidental entanglement in fishing nets, collision with boats, illegal fishing and habitat degradation.

Given the continuing decline in recent years, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declared in 2018 that Irrawaddy dolphins in the Visayas are critically endangered. The global conservation body estimates that only around six to 13 individuals remain in the area.

Despite this, the Irrawaddy dolphins were excluded from the 2019 feasibility study and the first environmental impact statement (EIS), which listed the plant and animal species to be affected by the Panay-Guimaras-Negros Bridge project. This surprised scientists like Dolar.

“The absence of Irrawaddy dolphins was really highlighted. It really kind of make[s] you feel uncomfortable because the very critically endangered large marine animal was omitted,” Dolar said.

Belated inclusion in the study

Under Presidential Decree 1586 or the Philippine Environmental Impact Statement System, proponents of mammoth infrastructure projects like the PGN Bridge must submit an EIS, a comprehensive study containing an assessment of a project’s anticipated effects on existing natural conditions, as well as plans to protect the environment, to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

The EIS serves as an application for an environmental compliance certificate (ECC), which is required before any project could proceed to the implementation stage. In June 2022, the DENR Environmental Management Bureau (EMB) issued an ECC for the PGN Bridge.

The feasibility study and EIS, which excluded the Irrawaddy dolphins, were led by Chinese firm CCCC Highway Consultants Co., Ltd., along with China Shipping Environment Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd and KRC Environmental Services based in Angeles City, Pampanga.

Marine scientists, including Dolar, have pointed out the “marked absence” of Irrawaddy dolphins from the EIS to the project proponents during the public hearing.

In a 2021 DPWH public hearing on the project in San Lorenzo, Guimaras, a representative of KRC said that Irrawaddy dolphins were absent in their study because their research teams did not see the species during their assessment period in March 2019.

“It’s understandable that they didn’t see Irrawaddy dolphins during their visit there. But we didn’t even know whether they took the boat and did a survey or just stood on land and looked out,” Dolar remarked.

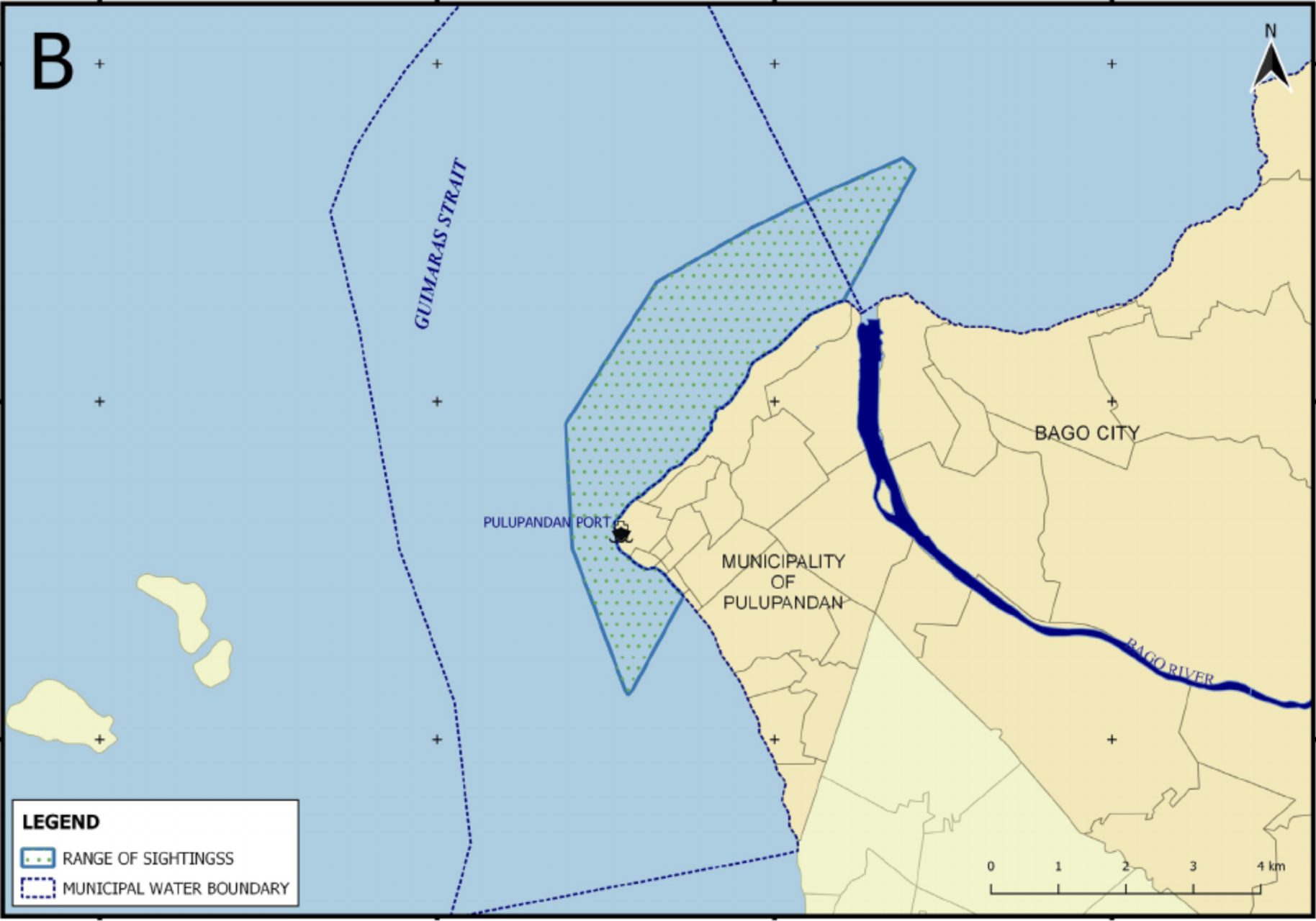

A revised EIS submitted to the DENR in 2022, a copy of which was obtained by VERA Files in 2024, already included the Irrawaddy dolphins among the species to be affected by the PGN Bridge construction after project researchers observed “sightings on Nov. 26 to 27, 2021” in Pulupandan.

While the EIS has recognized previous research on the species’ core habitat, it also noted that “perhaps, the proposed PGN Bridge alignment [has] been a rare roaming site of the Irrawaddy dolphins.”

But a 2020 study from the University of St. La Salle in Bacolod City identified a 12.68-square kilometer zone in the Bago-Pulupandan estuary as the main habitat of the Irrawaddy dolphins.

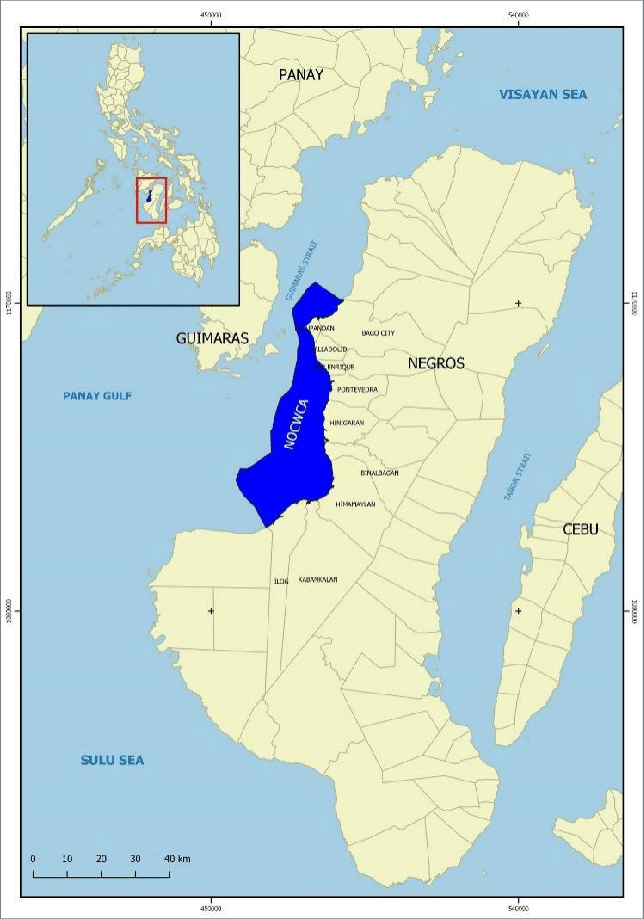

That core area also falls within the 109.52-kilometer stretch of the Negros Occidental Coastal Wetlands Conservation Area (NOCWCA), the seventh Ramsar site or wetland of international importance in the country. Wetlands are made Ramsar sites if they meet certain criteria, including the capacity to “support vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered species.”

The NOCWCA is tagged as an Important Marine Mammal Area by the IUCN due to sightings of dugongs or sea cows, another critically endangered marine mammal. It is also an East Asian-Australasian Flyway Network Site with 72 waterbird species recorded in the area, including the vulnerable Philippine duck, which lays eggs in the wetlands of Pulupandan.

Dr. Lisa Paguntalan, executive director of the Philippines Biodiversity Conservation Foundation, Inc., said that while the PGN Bridge alignment will not directly traverse the habitat of the Philippine ducks, construction could potentially affect the feeding ground of over 18,000 migratory birds in the NOCWCA.

“Because all of these [species] are tied up doon sa kanyang kinakainan, ‘pag naapektuhan ‘yung flow ng nutrients, maapektuhan din ‘yung food chain. Maaapektuhan din ‘yung magiging distribution ng species (to what they are eating, if the nutrient flow is affected, their food chain will also be. The distribution of species will also be affected),” Paguntalan pointed out.

But since the birds are migratory in nature, Paguntalan said they can look for another location should food availability in the area be affected. This, however, is not easy for the Irrawaddy dolphins, which are more dependent on a core habitat.

“Mas limited [ang] option ni Irrawaddy kaya mas malaki ‘yung magiging impact sa kanya (The options of Irrawaddy [dolphins] are more limited so there will be more impact on them),” Paguntalan added.

Despite this recognition from international conservation bodies, management of activities within the area is mostly left to local government units (LGU).

Existing conservation policies

In 2017, the Bago City government approved an ordinance that declared 130.39 hectares of its waters as a marine protected area for the Irrawaddy dolphins. Garbage dumping, active fishing and unauthorized entry into a 30-hectare “no take zone” is prohibited in the area. Violators face a fine of P5,000 or imprisonment of up to two months.

“‘Yung flagship species ng ating LGU (The flagship species of our LGU) [are] the Irrawaddy dolphins for protection,” said Vicente Mesias, head of the Bago City Environment Management Office. “We have today an environment which was declared as very important internationally. Dapat saluhin natin ‘yung responsibilidad na ito, dapat mapabuti (We should take the responsibility of preserving it).”

Under Republic Act 9147 or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, LGUs are allowed to adopt flagship species “which shall serve as emblems of conservation.” This, along with Republic Act 8550 or the The Philippine Fisheries Code of 1998, prohibits capturing or injuring vulnerable, threatened or endangered wildlife.

These laws, however, do not limit or regulate infrastructure projects from being built in the habitats of endangered species. Bago City’s protected area ordinance has no such provision.

VERA Files has reached out to the Negros Occidental Provincial Environment and Management Office and the local government of Pulupandan to ask about their programs and policies in protecting the Irrawaddy dolphins and the NOCWCA, and the potential impacts the PGN bridge could have on these, but has yet to receive a response.

Still, Mesias said they are conducting information and education campaigns among Bago City residents and local fishing communities to get them onboard in protecting the Irrawaddy dolphins.

Dolphins tell best time to fish

Rex, who also works in the city environment office, said his fellow fisherfolk are “always watching over” the dolphins, whose movements help them determine the best time to fish.

“Ginagawa sila namin na sign kung may mga isda. Kapag nagpapakita sila sa Bago City, ibig sabihin may hipon season na darating (We take them as signs when there are fishes. When they appear in Bago City, that means a shrimp season is coming),” Rex said.

Irrawaddy dolphins eat fish, cephalopods such as squids and octopus, as well as crustaceans like shrimps.

With the impending construction of the PGN Bridge, Mesias is hoping their efforts to protect the environment and the dolphins’ habitat will not be set aside.

“There might be other ways to do things. If we can make use of whatever it is na pwede nating gamitin and gawin sa area para maproteksyunan ‘yung environment (that we can use and do to the area to protect the environment), that could be a better option,” he added.

Mitigating measures

After the PGN Bridge’s feasibility study was completed in 2019, requests were made to the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) to reconsider the project’s location.

In August 2020, the IUCN sent a letter to then-secretary Mark Villar of DPWH, requesting proponents to “consider alternative bridge alignments that would allow for the safe and efficient transport of people and goods without sacrificing the region’s biodiversity.”

After two months, then-secretary Roy Cimatu of DENR wrote Villar to evaluate “areas outside of the NOCWCA,” like Victorias City and the town of Enrique B. Magalona, as entry and exit points of the bridge.

VERA Files has obtained copies of memoranda, issued by the DENR Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB) to the EMB, which reiterated this request for the project’s realignment thrice from 2021 to 2022.

Last May, the BMB wrote another letter to Public Works Secretary Manuel Bonoan and South Korean firm Yooshin Engineering Corp., which leads the PGN’s detailed engineering design, and “firmly reiterate[d] the realignment of the Guimaras-Negros Occidental section” away from the core habitat of the Irrawaddy dolphins.

The BMB met with the DPWH and the Korean contractors in March to discuss their recommendations on the project. The DPWH requested another meeting to talk about the request for realignment, but it has not materialized as of writing.

“The selected alignment of the project was chosen based on a thorough feasibility study which identified this as the most optimal option in terms of cost, engineering design requirements and overall project objectives,” Benjamin Bautista, director of the DPWH Road Management Cluster I, which handles foreign-assisted projects, told VERA Files during an Aug. 13 interview.

While he recognized that the PGN Bridge will “pass through the critical core habitat of Irrawaddy dolphins,” Bautista said they will be implementing mitigation strategies to address these concerns.

Among the mitigation measures mentioned in both the project’s EIS and ECC is the ramp-up technique, where low-level noise will be introduced “to allow dolphins or other protected species to leave” the construction’s high impact zone. Installation of noise attenuation technology like bubble curtains is also considered.

Construction activities are recommended to be “limited or halted” if Irrawaddy dolphins are spotted at least five kilometers from the construction site to avoid hampering their echolocation capability. Marine mammal observers will be stationed in the area to constantly monitor the presence of dolphins and other endangered animals.

But Dolar is unsure whether the ramp-up technique would work considering that Irrawaddy dolphins are tied to estuarine habitats where there is a mixture of freshwater and saltwater.

“If the ramp up process would drive them away, that means they can’t eat because that’s supposed to be their feeding ground. Hopefully, if they can find some habitat that [is] similar somewhere else, they will be able to go there,” Dolar said. “But the fact that they’re there means that’s probably the best place for them.”

She added that losing their core habitat would have a devastating effect on the dolphins’ ability to reproduce.

“[It] would create stress to them. The stress would prevent them from reproducing and will affect, of course, the future populations,” Dolar explained.

Mesias said that the dolphins may still be disturbed if they move into an area where people are not familiar to them.

“Kaya nga dito ‘yan siguro kasi ‘di sila disturbed dito. ‘Pag lumipat ‘yan sa ibang lugar and kulang sa [information] and advocacy ‘yung mga tao na nandoon, baka hindi maproteksyunan ‘yung mga Irrawaddy,” he said.

(Maybe they are here because they are not disturbed here. If they move to another place and the people there lack [information] and advocacy, the Irrawaddy dolphins may not be protected.)

Bautista assured the DPWH and the contractors will regularly assess the efficacy of their mitigating strategies and ensure that the conditions laid out in the ECC will be followed, especially during the construction period.

“We are committed in studying our plans carefully to safeguard our environment while trying to achieve the project’s objectives. We will not be sacrificing our environment just to complete this project,” he added.

With the PGN Bridge’s Guimaras-Negros section slated to begin construction in 2028 yet, Dolar is hoping there is still time to adjust its alignment away from the core habitat of the Irrawaddy dolphins.

“We’re not really against the bridge because that would help economically and also [for the] safety [of] people, but if it’s possible. [They should] find a place where [the bridge] can be placed without so much impacting the Irrawaddy dolphins,” Dolar said.

Mesias also hopes that the DPWH and contractors will take into consideration the marine scientists’ recommendations to safeguard the environment.

“What is good with economic prosperity kung iyong ating environment is already damaged (if our environment is already damaged)? If we can do something to at least minimize and ensure that the environment we’re protecting right now ay hindi sila maapektuhan (will not be affected),” Mesias added.

For his part, Rex is hopeful that there could still be a future for the Irrawaddy dolphins in the region. In his fishing trips in 2023, he saw three small Irrawaddy dolphins – two were the size of a small foxtail palm about 4 feet long while another was as big as a six-gallon water container.

“Hoping lang namin na mangyayari sa construction, make sure lang sana nila na ‘yung species na nandon hindi talaga masyadong mawala. Saka iniingatan din namin [‘yung Irrawaddy dolphins]… kasi nauna sila kaysa sa amin [at] hindi naman namin nakikita ‘yan sa ibang lugar.”

(We are hoping that during construction, they will make sure that the species there will not be gone. We are taking care of Irrawaddy dolphins because they came before us and we don’t see them elsewhere.)

READ Part 2: Visayas bridge construction still hangs 5 years after China’s withdrawal

(This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.)