Rodrigo Duterte does not watch his mouth.

A partial list of those he had publicly slighted so far: the pope, women, gays, rape victims, persons with disabilities (PWDs), the governments of Mexico, Australia, and the United States of America.

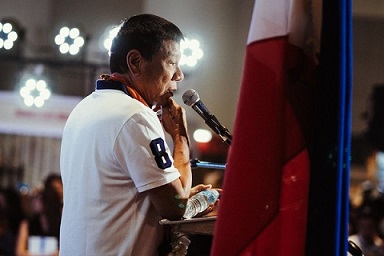

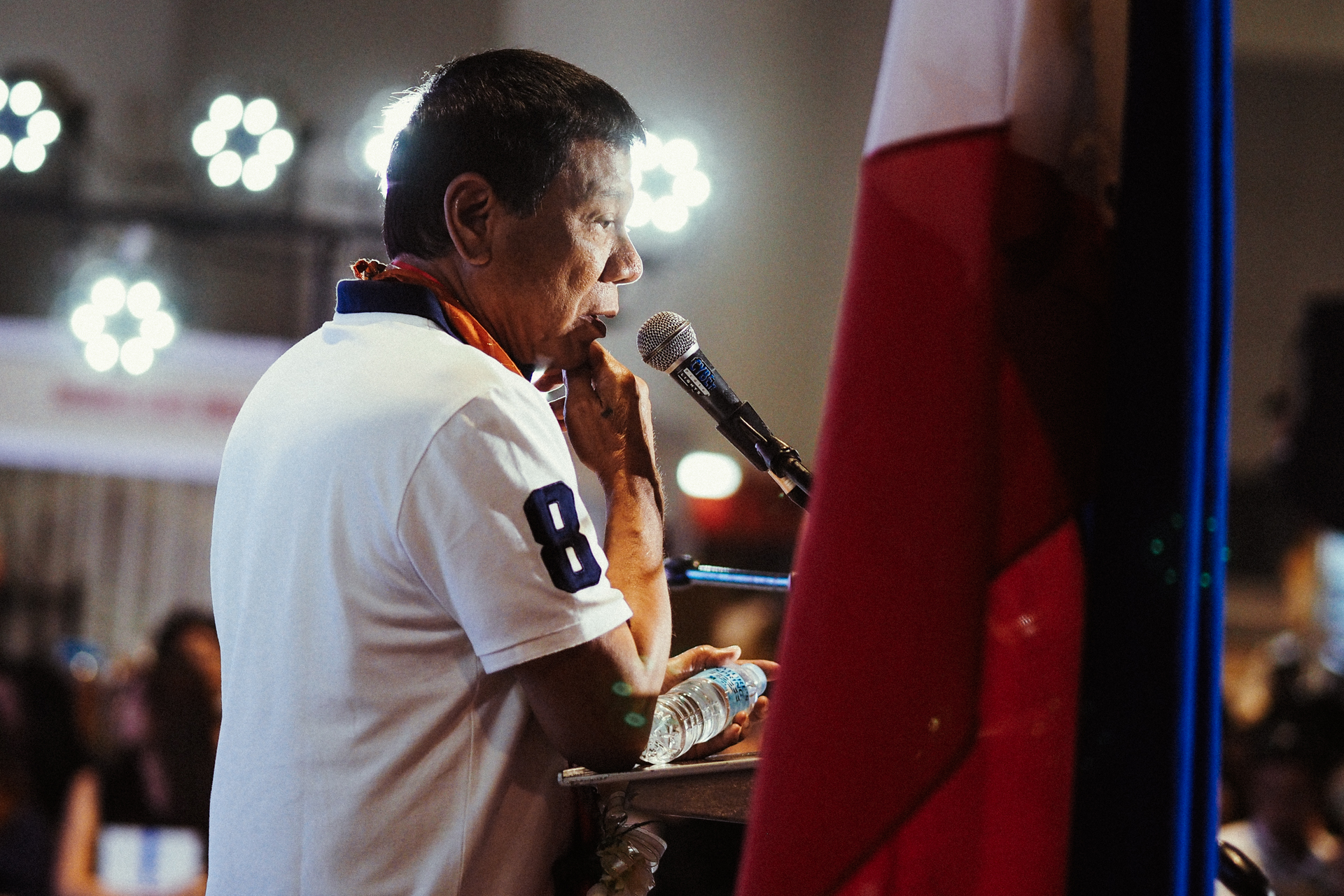

He is known for public cussing. One gets an endless supply of “Putang ina (Son of a bitch)” listening to him. In one campaign speech, in Muntinlupa, he used the phrase at least 23 times.

Unapologetic about these, he has said he is who he is, and would not change even if it costs him the presidency.

His supporters love him for it. Crowds during his rallies egg him on with cries of “Mura pa (Cuss) more!”

They see in the man something radically different from his opponents: he tells it like it is, dispenses with the typical guarded rhetoric, and seems to mince no words in his central campaign promise.

And the central campaign promise of Rodrigo Duterte, a latecomer in the presidential race, is simple: to suppress drugs, criminality, and corruption within three to six months after his election into office.

His pitch for the presidency centers on Davao City, where for 22 years now he has been mayor. Erstwhile the “murder capital” of the Philippines in the 1970s and the 1980s, the city is now, according to Duterte’s campaign website, “ranked as the 5th safest city in the world.” This he achieved through a “Punisher”-type approach against crime, an approach he says he intends to replicate for the entire country.

His campaign speeches — often long and long-winded, and peppered with profanity, innuendo, humor and street-style language — contain many references to killing criminals in the name of peace and order.

While his supporters online and off find these pronouncements, and the person himself, endearing, his detractors see a blood-curdling figure who when elected to the country’s highest post would lead it to bedlam.

Born in 1945, the 71-year-old Duterte, a lawyer, is modest about his education, saying he was not very bookish. He calls himself a “75,” a popular colloquialism for barely passing marks. Stories about his school antics are well-applauded in his campaign rallies, and he often punctuates these by leading his supporters in crying, “Mabuhay ang 75!”

He began his professional career in the mid-70s as a special counsel at the Davao City Prosecution Office, and then built his reputation as a city prosecutor by targeting both military and rebel abuses with equal fervor, says a report.

Politics ran in his family: his father Vicente Duterte was a former provincial governor. In 1986, Rodrigo was appointed OIC vice mayor of Davao City, and in 1988 was elected its mayor, a position he has held since, save for two brief three-year intervals, due to term limit restrictions.

The first of such intervals, from 1998 to 2001, he ran for and was elected Representative of the 1st District of Davao City. In the House, he sat in the committees on national defense, public order and security, health, transportation, and cooperative development.

Among the national bills he has filed as legislator are the decriminalization of libel concerning acts of government officials; an amendment to the penal code to punish public officers for directly taking part in compromise settlements of sexual abuse cases; and the prohibition of police personnel from the directly or indirectly arranging financial settlements between parties involved in sexual abuse cases, which made it as far as transmission to the Senate.

On his second break from the Davao City mayorship, from 2010 to 2013, he was city vice mayor to Sara Duterte, his daughter.

Though admired in some quarters, his record as mayor is also mired in controversy, especially as regards his alleged involvement in the extralegal killings of suspected criminals.

A 2009 report by international nonprofit Human Rights Watch (HRW), titled You Can Die Any Time: Death Squad Killings in Mindanao, notes that idyllic descriptions of Davao City “conceal a rampant crime wave—namely, the murder of hundreds of alleged drug dealers, petty criminals, and street children,” perpetrated by a vigilante group, or groups, called the “Davao Death Squad.”

A report the same year by Philip Alston, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, notes that Duterte “has done nothing to prevent these killings, and his public comments suggest that he is, in fact, supportive.”

The Commission on Human Rights, which has investigated the killings, recommended in 2012 that the Office of the Ombudsman “investigate the possible administrative and criminal liability of Mayor Duterte for his inaction in the face of evidence of numerous killings committed in Davao City and his toleration of the commission of those offenses.”

File a case if there is evidence is how Duterte responds to the issue. He ridicules former Justice Secretary Leila De Lima, the human rights commissioner who led in the investigation against him. He has called her “gaga” in one occasion, in another has sarcastically imitated her manner of speaking, to the uproar of the crowd.

This irreverence and disregard for rules of decorum have gotten him in trouble many times. Among others, he has cursed Pope Francis when he got stuck in traffic during the Papal visit; gaffed in front of the Mexican ambassador to the Philippines by making Mexico an example of a place not to visit when he was tried to make a point about illegal drugs and tourism; and publicly endorsed vice presidential candidate Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who is not his running mate.

But the one that elicited the most public outrage was his expression of regret that he was not the first one to rape an Australian minister, Jacqueline Hamill, who was killed in a bloody hostage-taking in 1989.

He related to the crowd, “Putang ina, sayang ito. Ang nagpasok sa isip ko, ni-rape nila, pinagpilahan nila doon. Nagalit ako kasi ni-rape, oo isa rin ‘yun. Pero napakaganda, dapat ang mayor muna ang mauna. Sayang. (Son of a bitch, what a pity. I thought, ‘They raped her, they lined up to rape her.’ I was angry because they raped her, well, there’s that. But she was so beautiful, the mayor should have been first. What a waste).”

Laughter can be heard from the audience, and then, cheering.

Although a lawyer, Duterte has mentioned forgetting the law of the land, appealing instead to a universal law, a karmic law, which when he elaborates is not unlike the Talmudic eye for an eye. This message seems to appeal to the majority of the electorate, judging at least by the results of recent presidential surveys, which rank Duterte the frontrunner.

This is no mean feat, considering he is the only local official in the race, and had only formally announced his decision to run for president in November 2015, when his opponents — the incumbent vice president, two incumbent senators, a cabinet secretary allied to the current administration — were already deep in their campaigns.

He could very well win in May with this message of swift justice, at the expense of basic human rights.

A succinct explanation for his popularity comes from Human Rights Watch, in the same 2009 report, which observed that the killings in Davao City “have not been unpopular.”

“According to a local human rights organization, fear and public frustration at ‘the arduous and ineffective judicial system’ have made summary executions seem a ‘practical resort’ to suppress crime,” the report read.

To a frustrated public, Duterte is the savior.