Disinformation and misinformation proliferated both on conventional and digital platforms during the 2019 elections, said researcher and UP Journalism Department senior lecturer Jake Soriano during the Sept. 13 Tsek.ph press conference at GT Toyota Asian Center in Quezon City. Photo by Celine Samson.

More than three months since the May 2019 midterm elections, the matter of who won and lost on the back of mis- and disinformation still looms large.

Bringing the issue to the fore is a recent bill filed by Senate President Vicente “Tito” Sotto III, which aims to combat “false content” online by penalizing its creators. The text of the measure mentions an instance where a hoax video showing a pre-shaded ballot “raised doubts as to the integrity of the automated election system.”

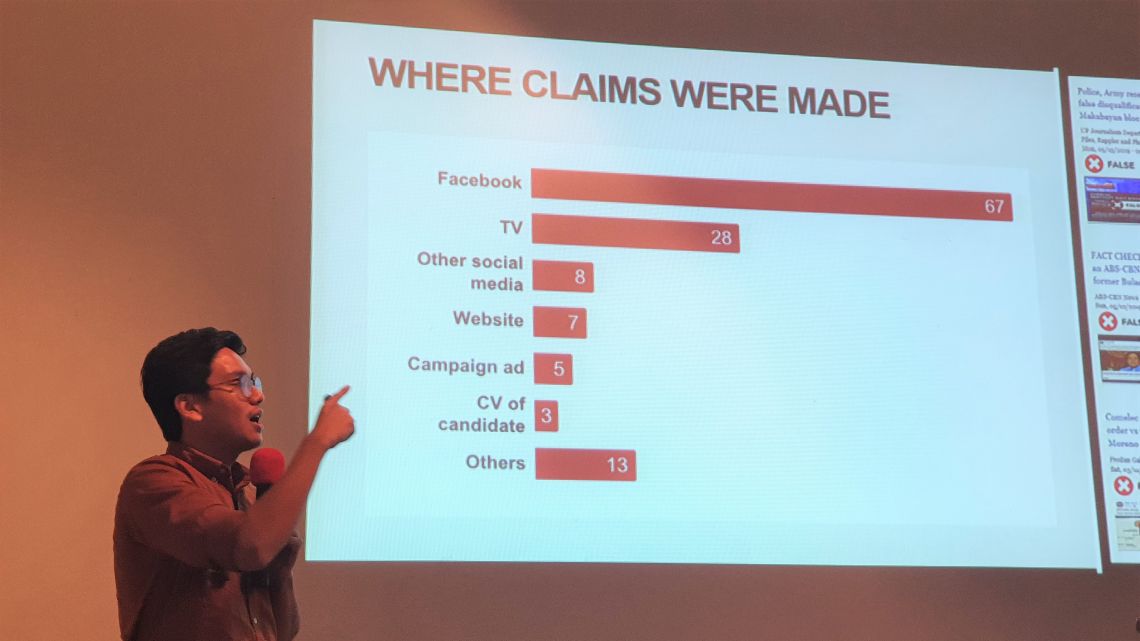

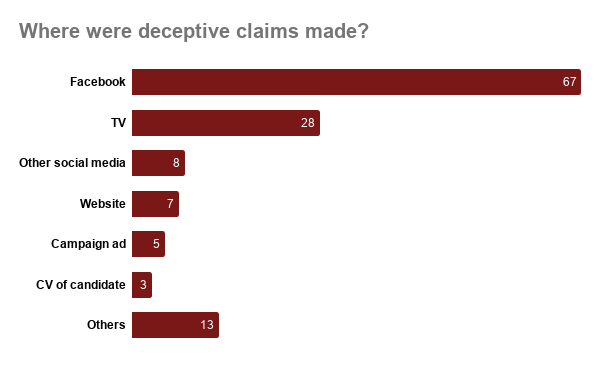

An analysis of election-related mis- or disinformation flagged by Tsek.ph, a pioneering collaborative fact-checking initiative between 11 newsrooms and three universities, shows, however, Senate Bill No. 9 rests on certain assumptions, such as framing “fake news” as if it were only a social media problem where the problem persists both online and off.

By seeking to penalize only “false and deceiving content online,” the bill neglects disinformation that spread through other vectors, which Tsek.ph data show were as prominent during the midterms as those on social media.

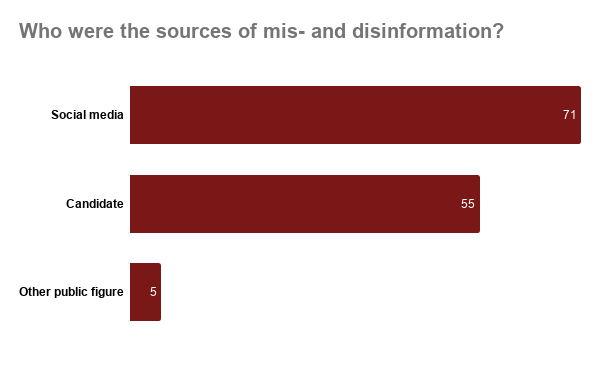

Indeed, more than half of the total 131 claims flagged by Tsek.ph in the runup, during and after the midterms were user-generated content that spread on social media.

One example: a doctored photo supposedly showing a massive Hugpong ng Pagbabago rally, which crudely edited images of the administration coalition candidates against a background photo of U.S. President Donald Trump’s inaugural speech to fake the crowd attendance.

The fake photo went viral on Facebook, and was tracked by analytics tool Crowdtangle before being taken down by its creators.

Another example: a fabricated screenshot purportedly showing media outfit and Tsek.ph partner ABS-CBN News reported anti-Otso Diretso Facebook accounts would be suspended. No such article was posted on the official ABS-CBN website.

But the other half were untruths or out-of-context statements made by candidates and other public figures themselves, in televised debates, public forums, speeches, campaign ads and even CVs.

As when then candidate and now senator Maria Imelda “Imee” Marcos falsely claimed first in her CV that she graduated from Princeton University, the University of the Philippines College of Law and a boarding school in California, and then repeated in a television interview her fictitious graduation from Princeton. Her claims were fact-checked by Tsek.ph partners and debunked by the institutions themselves.

Or when Duterte himself, in a speech just days before the elections, falsely claimed Otso Diretso candidate Lorenzo “Erin” Tanada III was previously elected senator and had defended communists in court.

On several occasions occasions, certain Senate hopefuls made false and misleading claimsdirectly on social media, through their official pages or accounts.

As when losing candidates Lorenzo “Larry” Gadon and Glenn Chong in Facebook posts made false claims against pre-election surveys and research organizations. Gadon made wrong assertions in an online video about Social Weather Stations (SWS) and Pulse Asia sample sizes, while Chong posted about topping an online poll, without stating the poll was informal and not scientific.

Facebook was the preferred social media platform of candidates in the last elections, perhaps owing to its massive use by the public, many of whom use “free basics.” Of the 62 Senate hopefuls certified by the Commission on Elections (Comelec), at least 30 had official Facebook pages that regularly posted content.

In the 17th Congress, Sen. Grace Poe, who in 2019 won in her reelection bid, proposed after several hearings on a bill seeking to criminalize “fake news” to provide stiffer punishments for government officials spreading false content after identifying this as a major gap in existing legislation.

Experts who attended the hearings had pointed out how officials like then Assistant Communications Secretary Mocha Uson were among the biggest purveyors of disinformation.

Tsek.ph documented how state-run and mainstream media amplified election-related disinformation, some of which can be traced to the candidates or their press releases.

In March, two months before the midterms, research organization SWS disowned a purported February survey supposedly showing then candidate and eventual winner Christopher Lawrence “Bong” Go had placed third for the period.

The information came from a media release from Go’s very own campaign bureau, which newsrooms, including the state-run Philippine News Agency, published, apparently without double-checking.

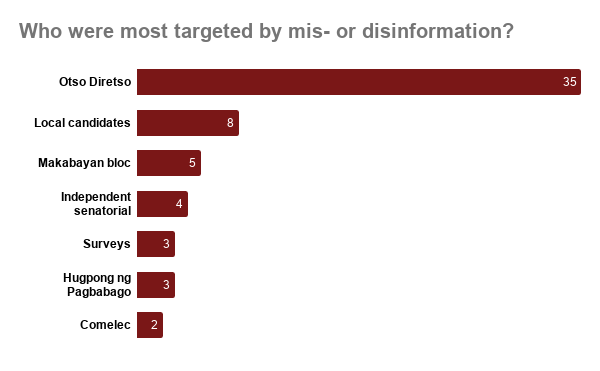

While hard to establish if election-related disinformation propelled certain candidates to victory and crushed the chances of others, the pattern that emerges from Tsek.ph data show those who were most targeted indeed lost their bids.

The opposition Otso Diretso slate—notably Manuel “Mar” Roxas II and Paolo Benigno “Bam” Aquino IV who based on pre-election surveys had the biggest chances of winning —was themost targeted by mis- and disinformation in the midterms; no Otso Diretso member won their Senate bids.

Roxas was a frequent victim of repurposed photos, a common strategy used by disinformation creators.

Months before the polls, multiple Facebook pages posted a photo of the Senate hopeful riding a padyak (cycle rickshaw) with a misleading caption criticizing his supposed gimmickry. The photo was taken during the runup to the 2010 elections, not 2019 as the posts suggest.

Roxas was also the subject of a false blog post claiming he had left the opposition slate.

Even after he lost his Senate bid, Roxas still became subject of false news, when an old altered photo spread on social media showing a woman offering him a rope tied into a noose. The fake photo first went viral in the runup to the 2016 presidential elections, and has already been debunked.

Meanwhile, Aquino was a frequent victim of fake social media quote cards, including one falsely claiming he said poor people should be fed leftovers or scavenged food.

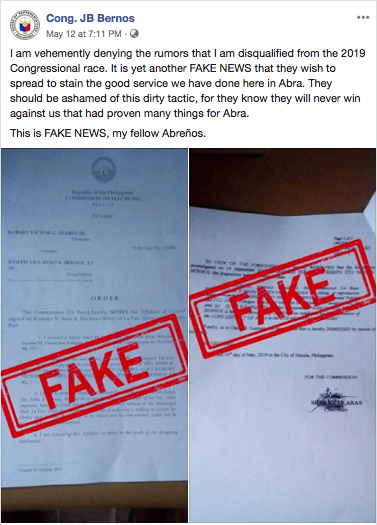

Certain local candidates who were targeted by fake disqualification content on social media up to on the eve and day of the polls are a distant second, only victims eight times to Otso Diretso’s 35.

Another political group that saw itself targeted by false or misleading content during the elections wasthe progressive Makabayan bloc, which fielded several party-list groups in the House of Representatives.

There were indications the attacks were state-sponsored; on election eve, a false post claiming Makabayan party-list groups had been disqualified appeared on a Facebook account claiming to be the police force of Iloilo City as well as four other accounts claiming to be Philippine army reservists in Mindanao.

In contrast, the administration Hugpong ng Pagbabago slate was victimized by mis- and disinformation only three times, based on Tsek.ph fact checks.

(Fact checkers from the University of the Philippines, a Tsek.ph partner, monitored all the candidates in the senatorial and party-list races to ensure nonpartisanship and fairness.– Ed.)

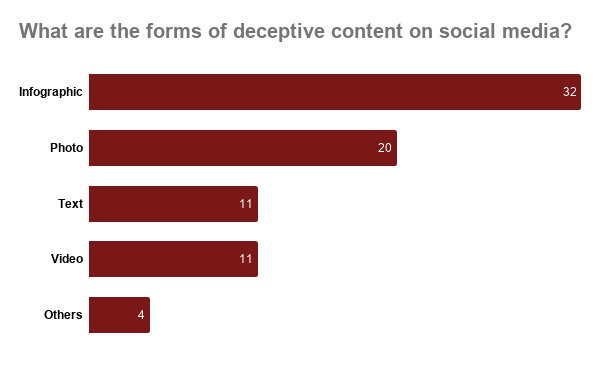

Altered photos or real ones but posted with out-of-context comments, and fake infographics are the most common types of false or misleading content related to the elections posted on social media.

Tsek.ph flagged infographics purporting to be survey results, or falsely showing invented or out-of-context quotes to attack certain candidates.

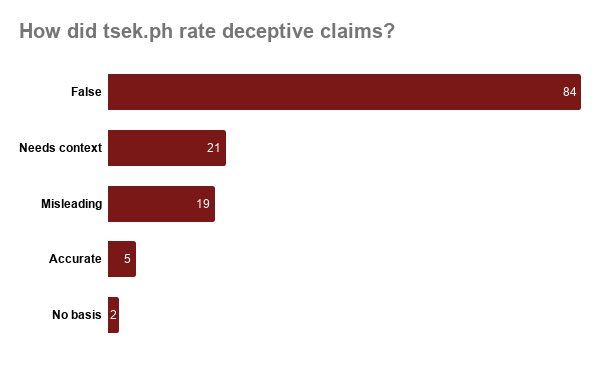

The “false content” bill in the Senate promises to be tough on the creators of these but does not seem to address the matter of disinformation being a spectrum.

Most of the claims and online content flagged by Tsek.ph—six in 10—are outright false. Most of the rest mislead or take out important context, but are still deceptive and inaccurate.

On election day, two Facebook accounts supposedly associated with the Agusan del Norte police published misleading posts redtagging a number of party-list groups; more than half of those in the list were not party-list groups or were not running at all.

An ad by former police chief and now senator Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa claimed credit for reducing the country’s volume of index crimes by 49 percent, but gave no time frame for the drop it highlighted and provided no clear basis for comparison.

Sen. Ramon “Bong” Revilla, recently made chair of the committee on public information and mass media had expressed readiness to immediately tackle the “false content” bill Sotto filed, saying “fake news” threatens the country’s political stability.

Revilla himself on election day was targeted by a post which altered his photo to falsely show him flipping the bird, one of the few times a member of the administration slate was a disinformation victim.

The bill says it “seeks to protect the public from the deleterious effects of false and deceiving content online,” aiming to do so by penalizing a broad category of acts that include the creation or publication of false or misleading information; offering services for such purposes; financing online disinformation activities; and noncompliance with rectification, takedown or block access orders, which the Department of Justice cybercrime bureau under the bill is authorized to issue.

If passed, the bill authorizes the justice department cybercrime office to determine content that would tend to mislead the public, but does not specify the standards to use in doing so, noted international organization Human Rights Watch in a statement calling for the measure’s rejection.

“The Philippines ‘false content’ bill, if passed, would make a government department the arbiter of permissible online material,” said Linda Lakhdhir, HRW Asia legal adviser. “A ‘fake news’ law would open the door for the government to wantonly clamp down on critical opinions or information not only in the Philippines, but around the globe.”

“The bill should immediately be withdrawn and revised to meet international free expression standards.”

(The Tsek.ph partners: ABS-CBN, Baguio Midland Courier, CLTV 36, DZUP 1602, Interkasyon, Mindanews, The Philippine Star, Philstar.com, Probe Productions, Rappler, Vera Files, Ateneo de Manila University, De la Salle University and the University of the Philippines. The authors are faculty members of the Journalism Department, which coordinated Tsek.ph.)