Susan F. Quimpo, co-author (along with her elder brother Nathan) of the best-selling family memoir Subversive Lives (Anvil Publishing Inc.), has been touring the country, often at her own expense, to talk about life under martial law and to present a slide show about what she calls the Lost Generation.

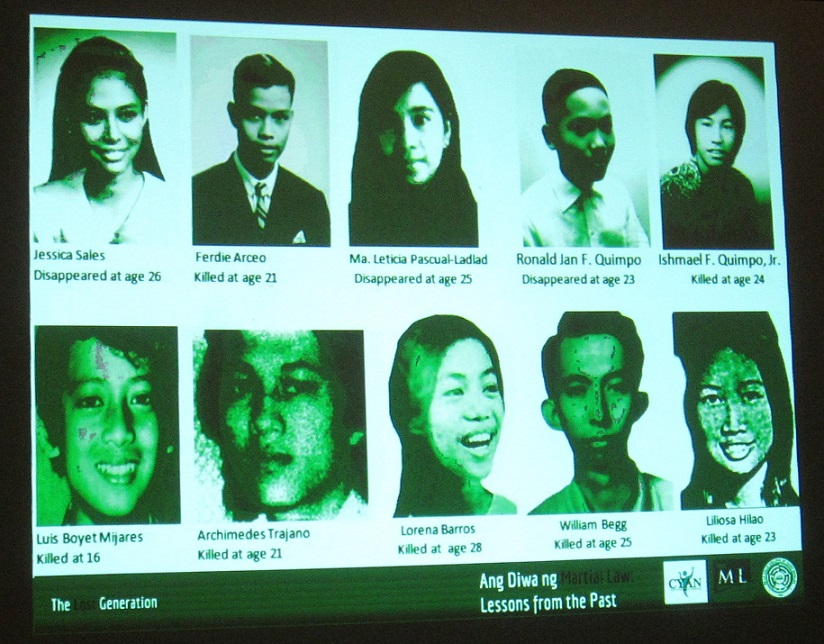

Members of this generation are those who were summarily killed and forcibly disappeared during the Marcos regime.

At an author’s talk at Mt. Cloud Bookshop in Baguio City, Quimpo used a PowerPoint presentation showing black and white photos of historic events leading to martial law and gave the background behind each slide.

Susan Quimpo signing a copy of her book

She traced how Ferdinand Marcos used public funds to win his reelection in 1969 and how the country was hit by inflation as a result. She noted that even then, Congress was already “full of crocodiles.” Marcos’s State of the Nation Address in 1970 was marked by a violent dispersal of rallying students.

At another rally outside Malacañang Palace, an activist nicknamed “Che” (because of the beret he was wearing) commandeered a fire truck to ram the palace gate. Quimpo did research on the guy. She found out that he was from Naga City. Later, he put up the first New People’s Army unit in Bicol.

Another brother Ronald, nicknamed “Jan,” became one of the early students of the Philippine Science High School in Quezon City. But PSHS then lacked the basic equipment. So the students, some as young as 12, went to the Palace to complain about the poor quality of education. The occasion became the youngsters’ politicization.

Among the rallyists was 15-year-old Francis Sontillano. While the students were marching, a security guard from Feati University, “with intent to harm,” according to Quimpo, threw from the school’s rooftop a Gerber bottle filled with gun powder, broken glass and nails. The bottle hit Sontillano and blew off half his head, thus making him the first PSHS martyr.

The atmosphere during those early years leading to martial law in 1972 and after was paranoid. President Marcos was afraid of students. Any meeting of at least three persons was considered an illegal assembly, Quimpo said.

She added that law enforcers were encouraged to arrest as many students as possible. Their incentive was P5,000 per activist arrested. That was a big sum then.

Her brother Jan was among those arrested. The lawmen’s reasons for picking him up was he carried a University of the Philippines identification card (ergo, an activist) and he had Chinese features so he must like communist China. He was tortured, electrocuted, his head dunked in a toilet.

Quimpo narrated that when Jan was eventually released, he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, but there were no psychologists to deal with this condition. He screamed in his dreams at night and would often fall from his bed. Jan left his house one morning just carrying a notebook. His family thought he was going to school. He has not been seen since and is presumed dead.

Victims of Martial Law

Another brother, Ishmael, nicknamed “Jun,” was the disco-loving, party-going Quimpo. He was arrested and tortured on the bases of being a UP student and being a Quimpo. Once released, he had a change of mind and heart about where he stood vis a vis Marcos. He joined the underground and rose in rank in the NPA. Later, he was killed by a fellow NPA member who he was taking to disciplinary action.

Quimpo said martial law’s damages include 75,730 human rights victims. This figure can be further broken down into 70,000 political detainees (poldets), 34,000 torture victims, 398 desaparecidos and 3,240 salvage (or summary execution) victims.

These victims make up what she earlier called the Lost Generation. She said, “They’re not rabble rousers. They’re smart scholars, intelligent kids who did the ultimate sacrifice.”

She stressed that “there was a dictatorship, there was a revolution not by a few but by millions of Filipinos. How was Marcos toppled? Not in three days, but it took decades.”

Asked what it felt like to have former First Lady Imelda R. Marcos and family in the political scene, she answered, “The martial law victims are hurt and confused, especially when Bongbong ran for vice president. It was a very frustrating time. For former poldets, especially the rape survivors, it was a time of crying as they relived the horrors.”

Quimpo still attends anti-impunity rallies and goes to different schools quietly asking officials if she or they can teach martial law history. At one forum, she was asked, “Why blame Marcos for what the country has become in the last three decades?”

Her answer was: “I cannot mourn my brother Jan. We do not have a body to bury while Marcos has a body and was buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.”