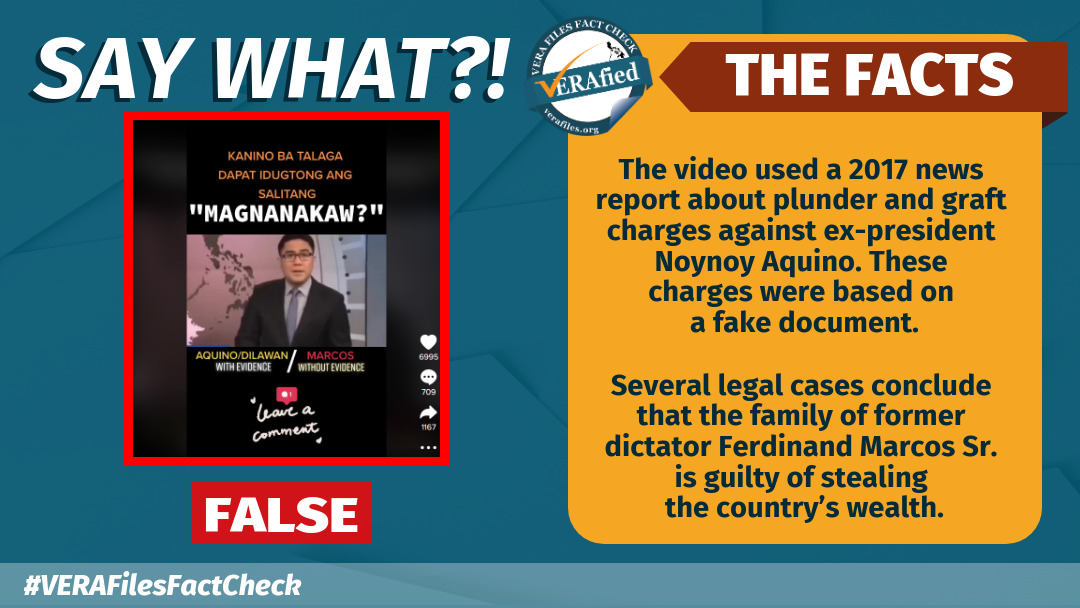

What do we do with the dark chapters in our history? We ingrain them in our collective consciousness by learning from them so that we can repudiate their revival. Critical readers aver that was easier said than done before the age of disinformation. The recipe does not change – we repudiate their revival – if truth against abysmal ignorance and revisionism is on our side.

When the Marcoses fled the Philippines in February 1986, they brought with them more than 2,000 pages of documents that exposed indubitable evidence of their opulent lifestyle. The papers were part of the Marcos cargo seized by US Customs and were later obtained under subpoena by a US House of Representatives subcommittee that investigated the grand robbery of the Philippines by the Marcoses.

When Ferdinand Marcos Sr. first assumed office, the country’s debt was US$599 million (1966). In 1984, that soared to a confounding US$24 billion. By the time he was ousted from power, we were in debt by almost US$27 billion. Until today, we are still paying the Marcos era debts until 2025, 59 years after he assumed office and 39 years after he was kicked out.

Disinformation is always selective. The UP economist Emmanuel S. de Dios contends that “Nearly three decades after it ended, still no proper account has been written of the economy under authoritarian rule, which is a big reason that Millennials have only an inkling of what transpired during those years. It is also why one now hears the mind-blowing judgment that ‘Marcos was the best president the country has ever had.”

The Marcoses loved banks. They deposited money in many banks overseas. Government after 1986 has since recovered some of these monies. Their cronies also put up their own banks that the Marcoses used as milking cows, like Roberto Benedicto’s Traders Royal Bank, Eduardo Cojuangco’s United Coconut Planters Bank, and Rolando Gapud’s Security Bank and Trust Company.

But they also loved government banks, the Philippine National Bank, the Development Bank of the Philippines, and the country’s primary institution in controlling money in circulation, the Central Bank of the Philippines.

Beginning 1981, the state of the CBP began its downward decline. After examining the bank’s losses in several Senate hearings from 1991 to 1993, the CBP was declared officially closed – there was nothing else that can be done to resuscitate its ailing health. A Central Bank Board of Liquidators was organized to liquidate its assets and liabilities and to close its books. That is the reason why a new law, Republic Act 7653, was passed creating the new Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas as a constitutionally independent monetary policy authority with fiscal and administrative independence, learning from the Marcos years.

What happened under the Marcoses? Those senate hearings uncovered how Imelda Marcos, her kids and kin, charged their numerous shopping sprees abroad to one of the suspense accounts of the CBP of which there were two: the Monetary Adjustment Account or the Exchange Stabilization Adjustment Account. A suspense account is an account in the general ledger where amounts are temporarily recorded, yet form part of the bank’s assets. This was bared on the senate floor by then senator Alberto Romulo who was majority floor leader, quoting bank insiders and reports in the Far Eastern Economic Review.

In addition, from the 1970s to 1980, the bank was also in the practice of the so-called foreign exchanges hedges – bearing costs incurred by Marcos crony firms due to depreciations of the peso.

But the old Central Bank as the Marcos piggy bank was not enough to fund the thievery. Rolando Gapud had testified in New York City that the dictator secretly acquired his bank, Security Bank, in 1980 and that he was tasked to personally manage a series of numbered accounts for the conjugal dictators.

The AP News reported on Gapud’s revelations: “Gapud testified that between 1982 and 1985, he transferred $50 to $60 million from the accounts for the purchase and maintenance of four New York buildings – 40 Wall St., the Crown Building at 730 Fifth Avenue, Herald Center and 200 Madison Avenue. The transfers were made on the instructions of Mrs. Marcos’ personal secretary, Fe Roa Gimenez.”

Gapud said all the accounts had “7700” numbers. The money transferred from Security Bank accounts went to corporations controlled by the Marcoses and were used to buy the buildings. At that time, there was a Central Bank regulation that limited the amount of US dollars allowed to exit the country. The scheme to circumvent the CBP was ingenious: dollar profits from exports of the Philippine National Oil Company were deposited into Marcos accounts in the US. Then the 7700 accounts would then pay the PNOC in Philippine pesos.

Gapud also bared that Philippine businessmen would submit fake applications to the CBP for approval to transfer dollars to overseas banks. In truth, the dollars were destined to Marcos accounts. The businessmen merely acted as fronts for Marcos. Gapud would then pay them in pesos from the 7700 accounts. Marcos was truly an astoundingly brilliant thief.

The Marcos fantasy was built on lies. Even the Central Banks’s dollar reserves in 1983 and thereafter was overstated in the books by $600 million. After the Ninoy Aquino assassination, business confidence was severely down, with capital flight debilitating the country’s international standing. Favored Marcos cronies could no longer pay their behest loans from the PNB, DBP and the Government Service Insurance System. The three institutions were in crisis. Our principal exports faced price declines in foreign markets, as essential imports like oil had sold to us at rising prices. Foreign banks refused to talk to Marcos government officials.

The overstatement was deliberately faked to show a veneer to foreign banks that we had the wherewithal to pay for our essential imports. The lie angered our international lenders.

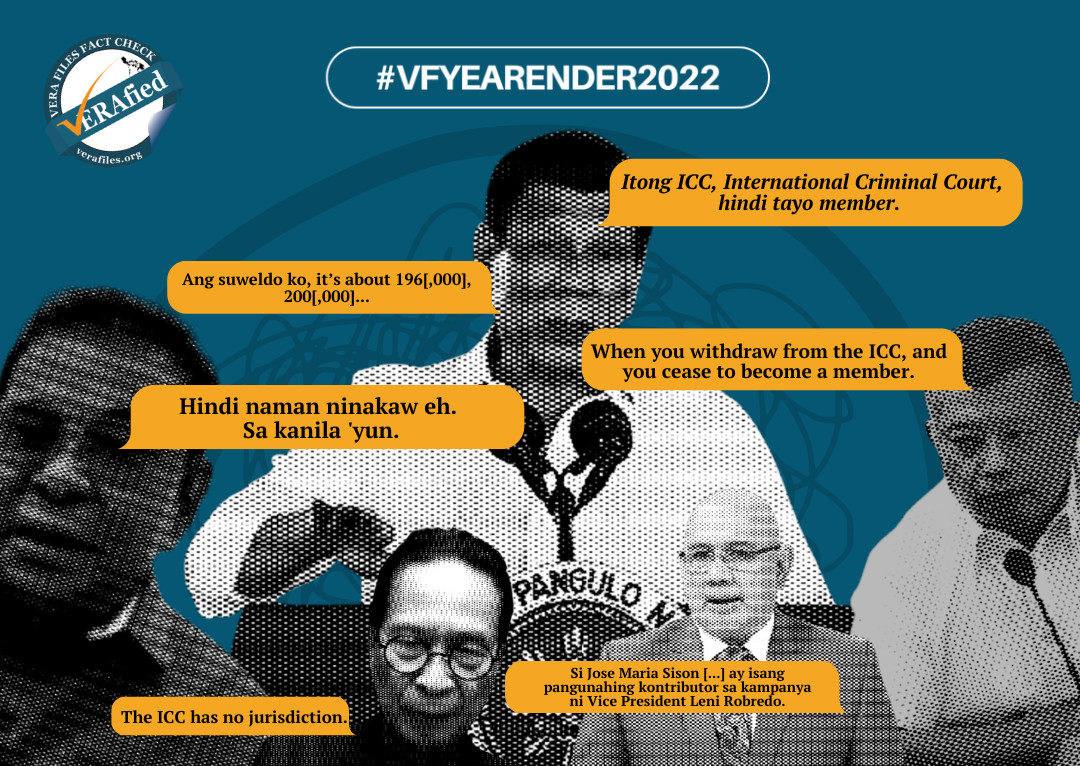

Marikina representative Stella Quimbo, she of the recent voice surrogating for the Marcos Romualdez family in the House of Representatives who seemed to have retreated from the controversy and backlash over the fakely named Maharlika Wealth Fund, wants us to believe the Bangko Sentral can fill in the P175 billion of the pension funds that the public has rejected. Economist and former Economic Planning secretary Winnie Monsod wheezes: the BSP profited last year by only P31 billion and hence cannot substitute for the P175 billion. Quimbo is fooling us in the name of the three Marcos Romualdez clique.

No, the Quimbo deodorant does not work for the stink of the Marcos-Romualdez record of corruption. The Maharlika Wealth Fund still smells. So the answer is still no.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.