It only took an uncouth invective said before a legislative hearing, then a bloody attempt to hurl a microphone of Congress at former senator Antonio Trillanes, and Rodrigo Duterte was chastised before our eyes. The message was clear – Duterte is deathly afraid of getting his dozens of bank accounts exposed more than his fear of the International Criminal Court.

Now that the cat is out of the bag, it is time to return to the 2016 issue of his bank accounts that Trillanes unsuccessfully tried to stall his presidential candidacy with for that year’s elections. Eight years have passed, at which time Duterte skillfully maneuvered his way out of the issue by clever means.

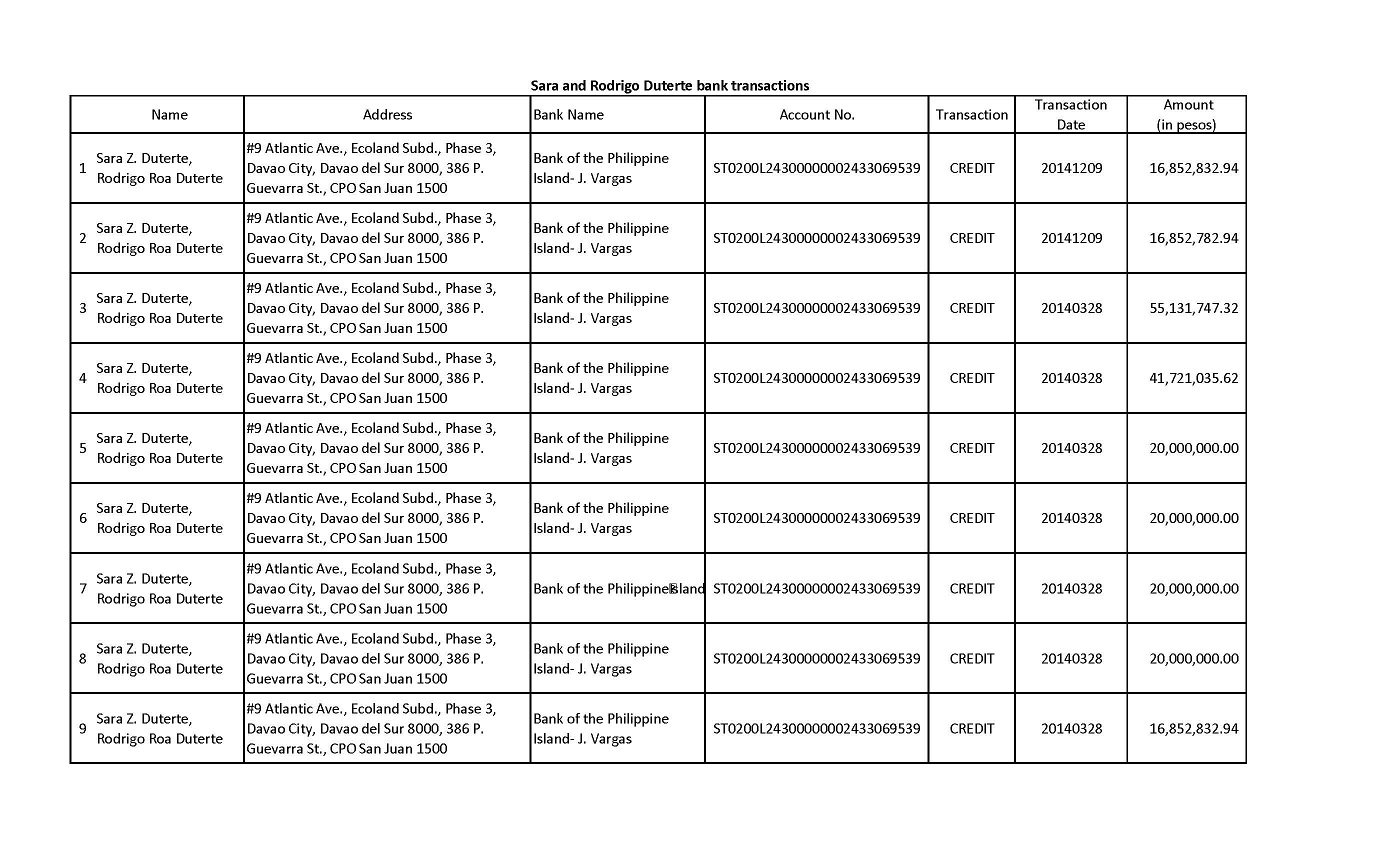

Recall that Trillanes first exposed the bank records because he was able to secure them from, according to him, the Anti-Money Laundering Council (how, we do not know). It then becomes essential to highlight a fact – when he had filed a plunder complaint against Duterte in the Ombudsman, the then Overall Deputy Ombudsman Melchor Arthur Carandang had stated in 2017 that the Trillanes copy of the bank records were “similar” to the AMLC records.

Carandang was polite. In fact, the transaction codes the AMLC requires for bank “covered transactions” (those above P500,000 for a banking day) tallied exactly with those in the Trillanes copy. It is far from being unsubstantiated.

The covered transactions involved numerous banks: BPI, Banco de Oro, Metrobank, Land Bank, Union Bank, Philippine Savings Bank, East West Bank, Asia United Bank, Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation, Philippine National Bank, Bank of Commerce and Security Bank. The Dutertes were all over the entire Philippine banking world.

This is where readers are earnestly invited to read the detailed summary of those bank records as written by VERA Files in 2018.

VERA Files had also reviewed the Statements of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth then of Rodrigo and Sara Duterte. The bank records were nowhere reported in their submitted SALNs.

Here are some of the important legal contexts. Aside from transacting huge amounts in one banking day, the Dutertes fall under what Republic Act 9160 (Anti-Money Laundering Act) classifies as “Politically Exposed Persons” or PEP, or persons entrusted with prominent government positions “with substantial authority over policy, operations, or the use or allocation of government owned resources.” If they had thought that their massive banking transactions were hidden, the lawyer Dutertes were ignoring the law.

As government employees, all Dutertes in public positions are mandated to file their SALNs by Republic Act 6713, the Code of Conduct for Public Officials and Employees. As prescribed, the SALNs must cover assets, liabilities, business interests and those of their relatives in government. Personal properties, for instance, must cover cash on hand (COH), cash in bank (CIB), investments (time deposits, negotiable instruments, securities, stocks and bonds), and insurance policies. Violation can range from fine to dismissal from government service to imprisonment of 5 years.

In BPI Greenhills Edsa, Rodrigo and Sara owned Account No. 0200131000000003103367386. In BPI Julia Vargas, they had Account No. ST0200124300000002433069539. It was in these accounts where the Dutertes would receive huge money placements over P40M in deposits in 2006 to 2007.

But for his 2006 SALN, Duterte only reported P6.07M in cash. They would also make investments through the bank’s Unit Investment Trust Fund (UITF). These as well were not reported in their SALNs. Records show they would make time deposits beginning 2011 in the BPI Julia Vargas account.

Sara’s individual accounts would also make investments out of her insurance policy. At one time she had P43.42M. Again, the proceeds of these investments were never reported in her SALN. They also had US dollar deposits. In 2010, it stood at $224,459.80.

There was also a pattern of deposits every March and October. As if on cue, there would be encashment of checks of about P10M each to Sara, Paolo, Sebastian Duterte and Honeylet Avanceña from an account of Cang Sammy Uy. The Davao Death Squad team leader Arturo Lascañas had alleged that Sammy Uy was a conduit of the illegal drugs trade of Chinese businessman Michael Yang.

Obviously, the Dutertes would have relied on a fund manager. It had to be someone known to and trusted by them, perhaps someone who hailed from Davao city. The writer columnist Marichu A. Villanueva of the Philippine Star believed she had found the identity of the Duterte fund manager.

Sometime 2019, Duterte appointed one Aurora Cruz Ignacio to two lofty positions: as president and chief executive officer of the Social Security System. It was deemed a midnight appointment – on the eve of the election ban on government appointments.

Who was Ignacio? Prior to her SSS stint, Duterte had appointed her as assistant secretary for special projects in the Office of the President in 2017. She was made Malacañang’s focal person for the anti-drug programs as member of the Dangerous Drugs Board.

But Marichu Villanueva had an endless curiosity. Who exactly was Ignacio in the Duterte universe? Using Google search, she stumbled upon intriguing information. Aurora Cruz Ignacio was from Davao city and used to work at the BPI Julia Vargas branch in Pasig. See how the Duterte web of impunity operates – he rewards government positions for persons who help him hide the truth about his illicit activities. It was just like rewarding his Davao Death Squad cop Royina Garma to the high government position of general manager of the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office.

Where you hide his crimes, he rewards you. Where you expose his crimes, the axe falls on you. The latter was the fate of Overall Deputy Ombudsman Melchor Arthur Carandang.

For stating that the Trillanes bank records match those of the AMLC, Duterte turned the heat on Carandang. On August 1, 2018, Executive Secretary Salvador “Bingbong” Medialdea, a Davao city childhood friend of Duterte, signed Carandang’s dismissal. Medialdea’s order said Carandang was liable for “graft and corruption” for stating in a television interview that he had evidence of the president’s ill-gotten wealth.

Earlier in January 2018, Malacañang issued a 90-day preventive suspension order against Carandang. Ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales refused to enforce the suspension, citing a Supreme Court jurisprudence that the Office of the Ombudsman was a constitutionally independent body in which the president had no authority to dismiss ombudsmen. The dismissal was thus illegal.

Morales cited the 2014 ruling by the SC declaring unconstitutional Section 8 (2) of Republic Act 6770 or the Ombudsman Law that previously gave the president the power to discipline deputy ombudsmen. But for Duterte, his pique and tantrum is the law.

When Carpio Morales retired on July 26, 2018, Duterte appointed his Lex Talionis fraternity brother Samuel Martires who then enforced the order to dismiss Carandang.

The current Marcos government should reinstate Carandang into service to correct his illegal dismissal. The Quad Committee of the House of Representatives should invite Carandang as witness/resource person. And the most ideal scenario – Rodrigo Duterte should sign the waiver to the Bank Secrecy Law.

So now we see as clear as day why he wanted to hit Trillanes in the Quadcom hearing with a mike. The rawest of all his nerves was hit – his hidden wealth. He is so deathly afraid of that getting exposed because it will only point to one thing – the Dutertes are thieves of public money.

#SignTheWaiver Mr. Duterte.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.