By PABLO A. TARIMAN

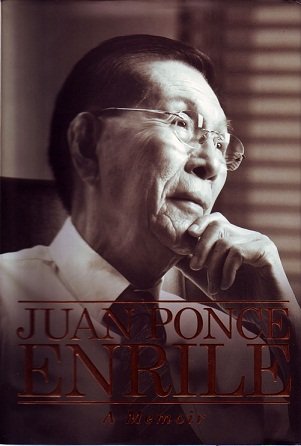

THE 753-page of “Juan Ponce Enrile: A Memoir” has many things going for it.

For one, the simple yet striking cover layout doesn’t call attention to itself and for another, it is well-edited (by Nelson Navarro) which makes for smooth, easy reading. It is, by turn, a no-nonsense book about someone’s life as he lived it and how he survived it.

Divided into two parts ( “With God and Guts” and “Making A difference”), the memoir has a unique voice you can’t mistake for a politician’s. The narrative flows with ease as the subject recalls the poverty-stricken barrio of his birth and ending his joining the government in the first part.

The first part is easily the most engrossing and the most poignant. The author — now well-known and famous — recalls the abject poverty of his past with startling details.

Born February 14, 1924, Juan Ponce Enrile (JPE) admits he was a love child baptized in the Aglipayan Church as Juanito Furagganan. His father, Alfonso Ponce Enrile, was born from parents from Baliwag, Bulacan. He notes that his grandfather, Damaso Ponce, was first cousin to Mariano Ponce of La Soledaridad, the propaganda arm of the Philippine Revolution of 1896.

In his own words, his mother was a young and attractive widow when she met his father — then a young practicing lawyer and promising politician in Aparri, Cagayan. At that time, Enrile’s father was married — not to Armida Siguion Reyna’s mother, Purita — but to one Rosario Martinez with whom he had several children.

Early in his young life, the then named Juanito Furagganan wondered why he looked different from his step-brothers who carried different surnames. On top of that, some people referred to him as the “bastard.” When his mother finally told him he was a child out of wedlock, he was shocked and decided not to ask more question.

Recalled JPE: “I noticed that she was reluctant to talk about my real father. I also sensed she was emotionally hurt. And so I dropped the matter altogether.”

JPE’s stepfather was a fisherman who never set foot in school. From him, he learned fishing at an early age.

But his mother, Petra Furagganan, made sure he went to school. He worked as houseboy for several relatives in exchange for free schooling and board and lodging. His first year high school at the Cagayan Valley Institute was his first taste of social iniquity. He was mauled by classmates who were part-owner of the school and when his guardian filed a complaint with the local police, he was expelled from the school without any investigation.

“The action of the supposed educators in the school totally dismayed me. They condoned the desecration of elementary justice. They had no compassion at all… For the first time, I saw a naked example of ‘palakasan,’ the evil that I was to encounter many times in my life,” JPE said in reflection.

When the Japanese attacked his hometown, the young Enrile joined the resistance movement and was caught later by the Japanese invaders. He was incarcerated in an Aparri jail where he was detained (and intermittently tortured) for more than 98 days. He was able to escape only when the Americans arrived.

On the whole, Book One of the memoir is the most readable and also the most heart-rending. Here, his first meeting with his real father took place when he hiked from his Sta. mesa address to his father’s office in Plaza Cervantes near Escolta. This was his first elevator ride and his first view of the city after his idyllic years in Cagayan. Then he finished his high school studies, took pre-law at Ateneo with cum laude and his law proper at UP again with the same academic honors.

The last part of the book chronicles his life as martial law administrator and his role working with five presidents of the republic from Marcos, to Cory Aquino, Fidel Ramos, Joseph Estrada and Gloria Arroyo. It ends with his role in the Corona impeachment trial.

For its wealth of details about his personal and official life, the memoir is a winner.

As to how much of it is credible is really up to the reader.

But it is easy to perceive in this memoir that JPE has come to terms with his colorful, if, stormy personal and political life.

On the whole, the book is first-rate sociology of the country’s social and political system. The scandals of the 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s and on to the new millennium give you an idea that nothing has changed. Only the leaders do. You also realize that in some cases, power and wealth don’t last (his account of rich and influential people who died penniless was indeed an eye-opener).

He concluded: “I have been judged and condemned many times. But I fear only the ultimate judgment of God and of history. People have different impressions about me, about you and about others so let it be…Indeed a strong and omnipotent power way beyond our human capacity to divine and comprehend directs each one of us to face our own destiny.”