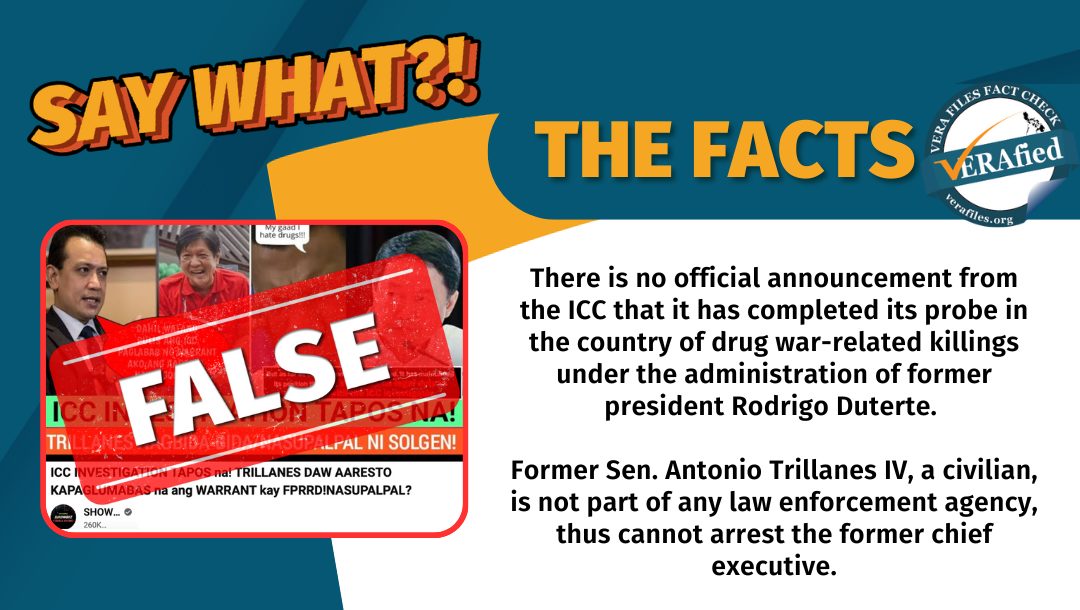

The record has not been so good for women who defy the authority of Rodrigo Duterte. The most awful of course was how he treated Leila de Lima.

Duterte would rather see women as subjects of his male domination. De Lima challenged that by asking for his accountability of the Davao Death Squad murders. His contempt for De Lima was proportionate to the bravado that she exhibited against his misogynistic disease. In short, he chickened out before a woman by punishing her for it.

As fate would have it, all three judges sitting for his pre-trial in the International Criminal Court are women. Has the time come for Duterte’s karmic retribution? How will he comport himself with women judges? Bluster and braggadocio are not part of judicial behavior in such a court, unlike in the Philippines. For sure, it will not be how he dealt with De Lima, Vice President Leni Robredo, and Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno. This is a court that cannot bend to political patronage, influence and disgraceful speech.

The reality has changed overnight: we have with us now a fully powerless Duterte. Will we see him in his bare and naked soul?

The ICC has a full compliment of eighteen judges who serve 9-year terms with no eligibility for reelection. They are elected by the member-states of the court, the Assembly of States Parties, the ICC’s governing body. All candidates must be nationals of member countries. As a rule, no two judges may be nationals of the same state.

To qualify as judge, the legal capacities needed are those in the field of international law (an unknown in the Philippines as we can see at present), international humanitarian law, the law of human rights, and expertise on relevant issues such as (but not limited to) violence against women and children.

The Rome Statute’s rules on judicial gender require that there are at least six female judges and at least six male judges. The eighteen judges are organized into three divisions: Pre-Trial Division, Trial Division, and Appeals Division. Judges are assigned to their divisions on the basis of their expertise.

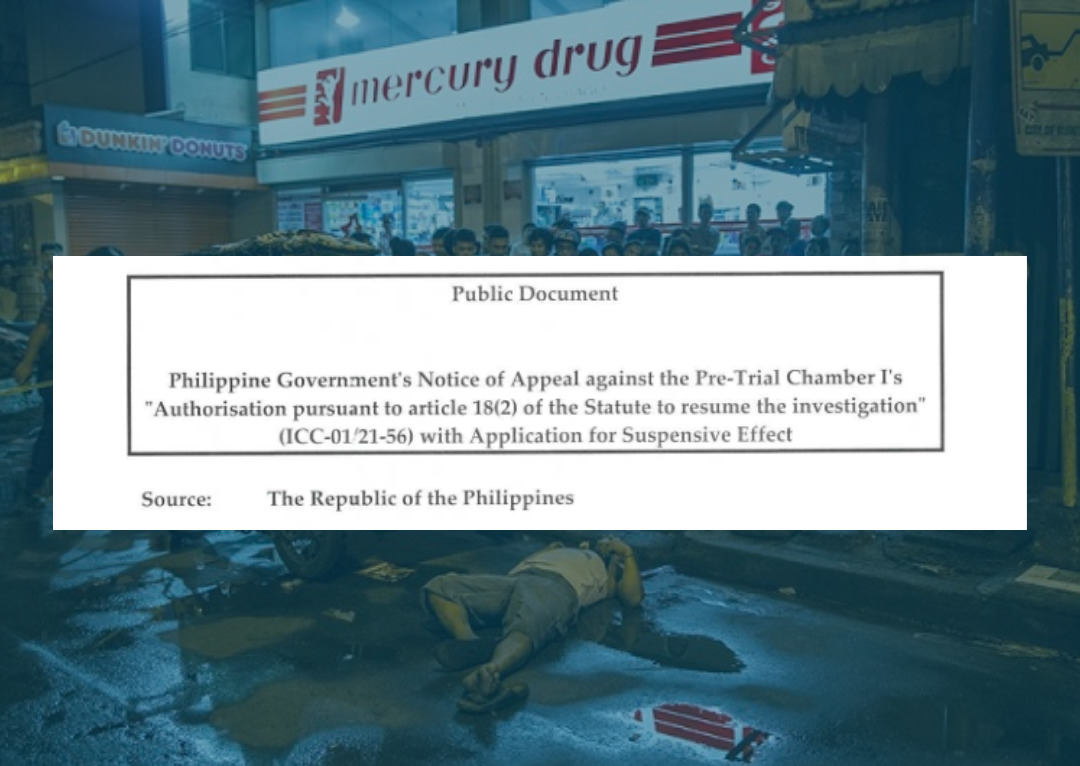

Duterte’s present pre-trial fell under the Pre-Trial Chamber 1. This chamber is also presently committed to the investigations on the Bangladesh/Myanmar Rohingya Genocide, the situation in Venezuela involving crimes against humanity perpetrated by civilian government and military officials, and the war crimes in Mali, among others.

With such investigations that are of distinguishing import to world affairs, one can already see the formidable judges who comprise the Pre-Trial Chamber 1.

Iulia Antoanella Motoc of Romania is the presiding judge of this chamber. Her expertise is international law. Formerly, she sat as judge at the European Court of Human Rights. She was also a professor of international law at the University of Bucharest and had also sat as judge in the Constitutional Court of Romania. She had also taught at the New York University School of Law where she was Senior Jean Monnet Fellow.

With her expertise, Motoc wore various hats. She once was UN Special Rapporteur on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and was vice president of the UN Human Rights Committee. She graduated law from the University of Bucharest, her masters from the Paul Cézanne University School of Law in Aix-Marseille, France where she also graduated for her doctorate in international law summa cum laude. She holds another doctorate in ethics from the University of Bucharest Department of Philosophy. She was a fellow in philosophy at the Yale University School of Law in New Haven, Connecticut.

Reine Adélaïde Sophie Alapini-Gansou of Benin has been an ICC jurist since March 2018. She has a degree in Common Law from the University of Lyon in France, a master’s degree in business law and judicial career from the University of Benin. She holds a joint postgraduate degree from the Universities of Maastricht (The Netherlands), Lomé (Togo) and Bhutan.

She has taught general criminal law and criminal procedure at the University of Aborney-Calavi in Benin. She has been consultant for the World Health Organization and the International Labor Organization, both for the human rights of mentally ill people. She has been appointed to several UN commissions on human rights violations. In 2011, she was appointed as judge in the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Peace Palace in The Hague, the Netherlands.

For 12 years, she was a member of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. She chaired that commission beginning 2009. In September 2016, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon appointed her as member of the Commission of Inquiry into Human Rights Violations in Burundi. Note: Like the Philippines under Duterte, Burundi under its president Pierre Nkurunziza also withdrew from the ICC as a reaction to investigations on extrajudicial killings he had allegedly perpetrated.

In 2010, the prestigious French Academy of Sciences in the Sorbonne (a.k.a. University of Paris) awarded Alapini-Gansou the Laureate of the Prize of Human Rights.

Maria del Socorro Flores Liera is a jurist and diplomat from Mexico. Prior to the ICC, she was Mexico’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Geneva. When she was elected judge for the ICC, she obtained the highest rating by the ICC’s Independent Experts Report and the highest number of votes among the participating eighteen candidates. Her specialization is public international law.

She is the first Mexican to sit in the ICC and the first Mexican woman in an international court. In the Foreign Ministry of the United Mexican States, she has served as Undersecretary for Latin America and the Caribbean, Director General for Global Issues, Director General for American Regional Organizations and Director of International Law in the Office of the Legal Counsel.

Flores was a member of the Mexican delegation in charge of negotiating the Rome Statute, both in the Preparatory Committees and in the Rome Conference and, between 2006 and 2007, she was Mexico’s Head of Office for the ICC to the United Nations.

She studied law at the University of Ibero-Americana and at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico on public international law. She has published works on international criminal law, international cooperation, and climate change.

When the complaints against Duterte were filed in 2017, he had mocked the then ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda of The Gambia as “that black woman.” In the same breath, he also called the noted French human rights activist and former UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Agnès Callamard (today secretary general of Amnesty International) as “malnourished.” “Don’t f**k with me girls,” he said in a speech to Philippine government officials, referring to Bensouda and Callamard.

That “Don’t f**k with me girls” line is now gone. Duterte could no longer say that to the three illustrious women judges of the ICC with whom he could not play the fool. That is why his extradition to The Hague was important where his influence has no tentacles. Imagine what commotion and insults he would throw if he were tried in a Philippine court. The payback time has arrived.

The era of Duterte invectives and insults is now gone because the devil is no longer his judge.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.