In two weeks, the Philippine Space Agency (PhilSA) issued two advisories warning the public of the potential risks of falling debris from two space rockets launched by China.

On Jan. 9, PhilSA alerted the public on the projected drop zones of rocket boosters and other debris from Long March 7A, which was launched early that day from the Wenchang Space Launch Center in China. These were expected to scatter in the surrounding waters of Babuyan Islands, Cagayan and Ilocos Norte.

On Dec. 29, 2022, almost two weeks earlier, the space agency had likewise warned about the debris coming from the Chinese rocket Long March 3B which was projected to fall around Recto Bank in the West Philippine Sea.

Although the rocket waste is not expected to fall on land, PhilSA cautioned that fragments could pose danger and potential risk to ships, aircraft, fishing boats and other vessels passing through the landing zones.

What are orbital debris and the risks they pose? What to do when you see them? Here are four things you should know:

1. What are orbital debris?

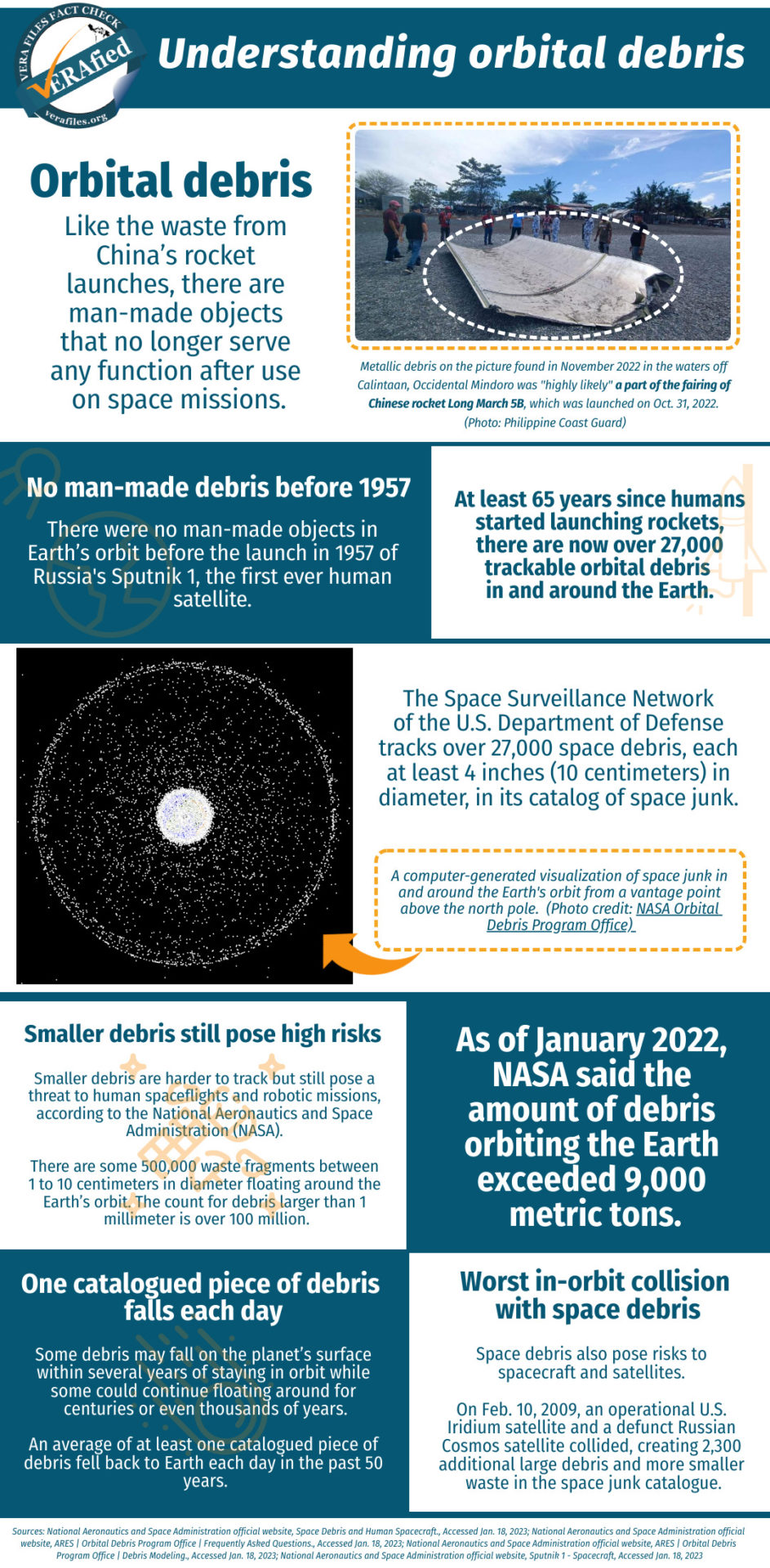

According to PhilSA, orbital debris are man-made objects circling the Earth that could fall back to the planet or collide with other objects in orbit. These include non-functional spacecraft, launch vehicle stages, defunct satellites and fragments like paint flecks which are considered junk and no longer serve any use.

However, PhilSA told VERA Files Fact Check in a Jan. 18 email that not all debris from rocket launches complete an orbit around the Earth. Some like payload fairings and rocket boosters are discarded several minutes after the launch and are designed to fall on uninhabited areas called drop zones.

According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) of the United States (U.S.), orbital debris are generally considered “space debris.”

Currently, over 27,000 trackable space junk are in the Earth’s orbit, based on the catalog of the Space Surveillance Network of the U.S. Department of Defense. PhilSA does not have the capability yet to track space debris.

2. What are the potential dangers to humans, properties of falling debris?

PhilSA has repeatedly cautioned the public in its advisories not to touch or come in close contact with any orbital debris which could contain remnants of harmful chemicals such as rocket fuel and cause damage to aircraft and fishing boats in the drop zones.

The space agency, however, clarified that the risk of this happening is relatively low since the majority of drop zones are in the water. Smaller debris may burn up in the atmosphere, but larger fragments could land on shallow waters and damage coral reefs or hurt marine animals.

There have been no recorded casualties or damage to property caused by space debris in the Philippines, according to PhilSA. In human history, only one person from Tulsa, Oklahoma in the U.S. was identified by NASA to be hit by a falling fragment — about six inches of metal — from the American rocket Delta II in 1997.

Despite this, PhilSA said the lack of intervention to prevent such an incident within the next decade may put a probability of between 6% and 10% of a human being killed or severely injured by falling space junk.

In terms of significant environmental effects, the space agency said the crash of Russian nuclear-powered satellite Kosmos 954 in 1978 is the only documented case. The crash of the satellite in the Northwest Territories of Canada resulted in the scattering of radioactive debris in over 124,000 square kilometers.

PhilSA noted that there are ongoing studies worldwide on the compounded negative effects of space debris on the environment.

3. Who can be held liable for the damage to property or fatalities due to falling debris?

According to the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, the state that owned and launched an object into outer space is liable to pay compensation for damage such as loss of life or injury of a person. In the case of one or more states involved in a joint launching of a space object, they can be held liable jointly or severally for any damage caused.

The complainant state must present its claim for compensation to the launching state through diplomatic channels not later than one year from the occurrence of the damage or identification of the liable state. If there is no diplomatic relations with the launching state, the claimant state may ask another state to present its claim, represent its interest under the convention, or course it through the United Nations (U.N.) secretary-general provided that both of the involved parties are members of the international body.

A three-member Claims Commission may also be set up pursuant to Article XIV of the Liability Convention if no agreement is reached through diplomatic negotiations.

PhilSA said it is prioritizing the ratification by the Philippines of the Liability Convention and Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space. Until the ratification, the Philippines would not be able to invoke the two conventions to claim compensation for damage or injury from space objects of other states.

“However, we may still seek compensation through other mechanisms as customary rules of international law relating to state liability and state responsibility shall still be applicable to the space law regime,” the agency assured.

4. What should the public do if they encounter orbital debris?

PhilSA advised the public to immediately inform local authorities of the sighting while keeping a distance due to possible toxic substances.

Under the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space, the country where the debris is found should notify the launching state and the U.N. secretary general. Since 1968, the U.N. Office for Outer Space Affairs has been maintaining a public database of orbital debris discovered in the territory of member states, on the high seas, or in any other place not under the jurisdiction of any state.

Under the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space, the country where the debris is found should notify the launching state and the U.N. secretary general. Since 1968, the U.N. Office for Outer Space Affairs has been maintaining a public database of orbital debris discovered in the territory of member states, on the high seas, or in any other place not under the jurisdiction of any state.

Although the Philippines has not ratified the Rescue Agreement, PhilSA said the government may comply or abide by the principles of the treaty “in good faith,” such as retrieving and returning the debris upon the request and assistance of the responsible state.