The government’s decision to grant Chinese tourists and investors a 14-day visa-free entry is being presented as a pragmatic economic move meant to revive tourism, attract investments, and keep the Philippines competitive as Chinese outbound travel rebounds.

On paper, the policy targets immediate, specific and short-term benefits: easier entry, more arrivals and economic stimulus. In practice, however, it cannot be separated from the wider and far more volatile context of relations between the Philippines and China, most notably the unresolved and increasingly tense dispute in the West Philippine Sea, lingering public mistrust, and the still-unsettled issues surrounding Philippine offshore gaming operators (POGOs). A visa policy does not exist in a vacuum; it communicates intentions as much as it grants privileges.

Visa liberalization is a common tool of economic diplomacy, and Manila has extended similar privileges to many nationalities in the past. Citizens of much of Europe, North America, Australia and parts of Asia and Africa already enjoy visa-free entry for 30 days or more, under Executive Order 408 issued in November 2014. Even Indian passport holders were granted eased conditions in 2025. In that sense, a 14-day window for Chinese travelers is not extraordinary.

What makes it contentious is timing and context. The policy was announced on the eve of implementation, amid continuing maritime tensions and after years of Philippine reluctance to extend such privileges to Chinese nationals. When Chinese vessels continue to challenge Philippine maritime rights, block resupply missions, and assert claims rejected by international law, easing entry requirements risks being read not as confidence but concession.

That does not mean the policy is indefensible. Economically, the case is straightforward. China ranked only sixth in the country’s overall inbound arrivals as of Dec. 20, 2025, with 262,144, far behind South Korea, the United States and Japan. Before the pandemic, and before relations soured, Chinese nationals were the second-largest source of foreign visitors, with 1.7 million, trailing only South Korea in 2019.

Neighboring states such as Thailand and Malaysia have moved aggressively to capture the rebound in Chinese travel. In that context, Manila risks being left behind. A limited, revocable 14-day waiver is hardly an open-ended concession.

Officials insist the policy is purely economic and does not dilute the country’s legal and sovereign claims. National Security Adviser Eduardo Año has said security measures apply regardless of nationality. Formally, that may be correct. But diplomacy is not conducted through formalities alone. It is also conducted through symbols and sequencing. Offering a visa-free privilege without parallel de-escalation or confidence-building from Beijing raises questions about leverage used too lightly.

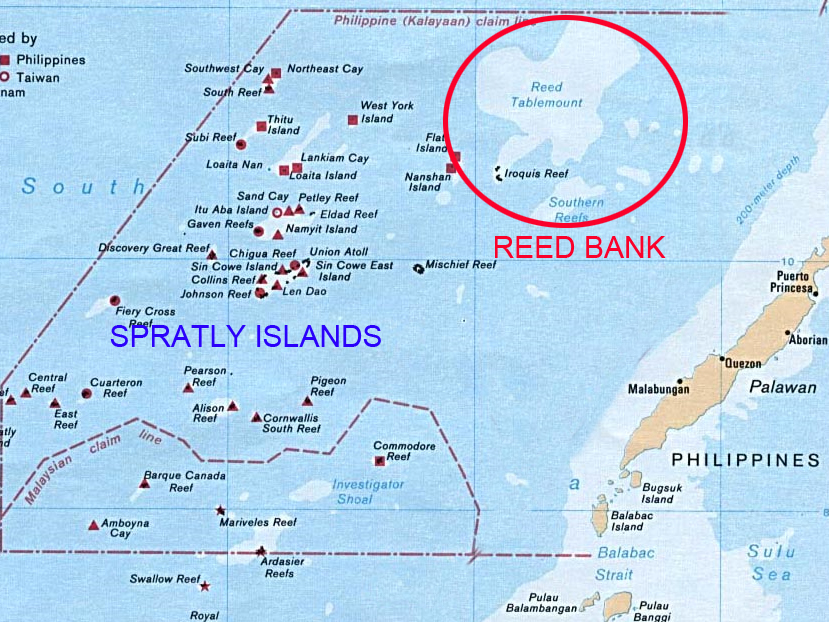

The contrast is difficult to ignore. While doors are being opened wider to visitors, Filipino fishermen still face restricted access to traditional fishing grounds. The same state whose tourists are being courted is also the one whose coast guard vessels continue to harass Filipino boats and obstruct resupply missions. Left unaddressed, these contradictions reinforce a public perception that economic courtesies are being extended without reciprocal respect for sovereignty.

The administration has been careful to say it will not trade away rights for tourism or investment. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has repeatedly affirmed adherence to the 2016 arbitral ruling and to international law. But policy coherence demands more than speeches. It requires incentives to be sequenced and explained as part of a broader strategy, not rolled out in isolation.

Visa-free entry is leverage. It can be granted, adjusted or withdrawn. Used well, it can be paired with clear expectations, reciprocal steps or at least a demonstrable easing of tensions. Used poorly, it becomes a one-sided gesture that weakens negotiating posture.

There is also the shadow of POGOs. What began as a revenue experiment metastasized into a source of crime, corruption and security anxiety. The crackdown and phaseout were welcomed not out of xenophobia, but because regulation failed. For many Filipinos, “Chinese investors” is no longer a neutral phrase; it carries memories of illicit hubs, bribed officials and disrupted communities.

Against that backdrop, assurances that the visa-free policy is strictly for tourism and legitimate investment must be backed by enforcement. Transparent reporting on overstays and violations is essential. Given persistent perceptions of corruption in immigration and law enforcement, abuse is not a hypothetical risk. Without credible safeguards, the policy could reopen doors that were closed only after considerable political cost.

Engagement with China is not inherently incompatible with firmness in the West Philippine Sea. The two can coexist, and even reinforce a rules-based posture, if boundaries are explicit. What undermines credibility is not engagement itself, but the absence of visible guardrails. A confident state can welcome visitors while refusing to be intimidated. A muddled one sends mixed signals that invite pressure.

Ultimately, the question is not whether Chinese tourists should be allowed in for 14 days without a visa. It is whether the state can show that openness is a tool of national interest, not a substitute for strategy. Filipinos have shown they can support engagement when it is paired with vigilance. What they will not accept is pragmatism without principle.

If this policy is to succeed, the administration must show that opening the door does not mean lowering the drawbridge, especially when the shoreline remains contested.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.