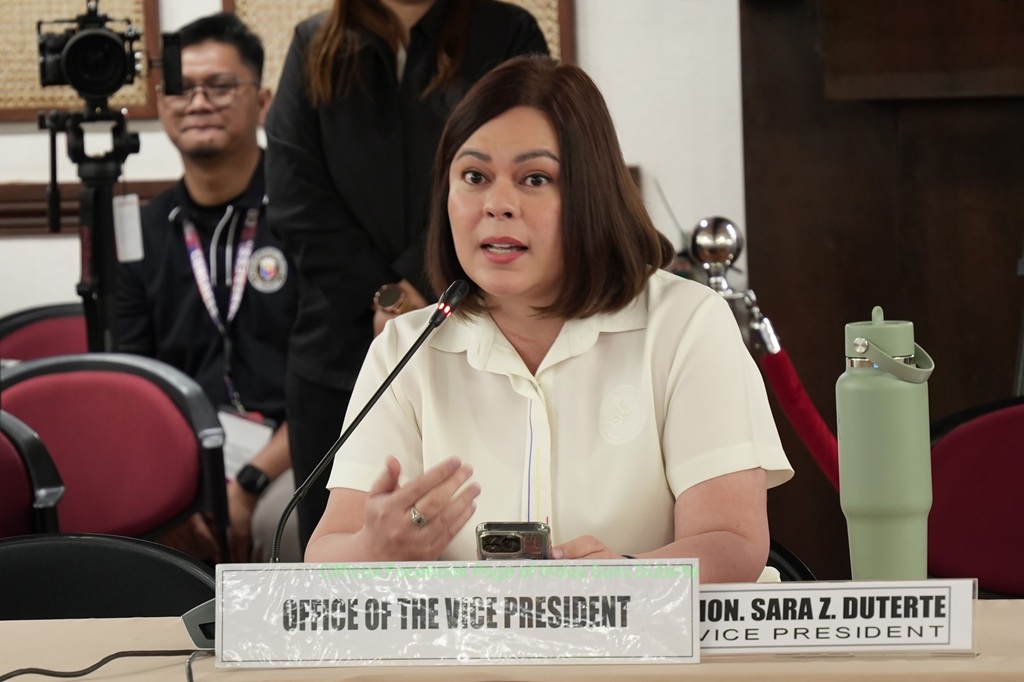

The Supreme Court’s decision on Thursday to dismiss the appeal seeking to overturn its July 25, 2025 ruling, which declared the Articles of Impeachment against Vice President Sara Duterte unconstitutional, did more than settle a procedural question. It reshaped the political terrain heading into the 2028 presidential election, buying time for one of the country’s most prominent political figures and reviving broader questions about accountability, dynastic power and the rule of law.

For those who welcome the ruling, it stands as a clear affirmation of constitutional process. It reinforces that impeachment is not merely a political tool but a legal mechanism bound by strict procedures and safeguards. As Senior Associate Justice Marvic Leonen wrote in the original decision, “There is a right way to do the right thing at the right time,” underscoring that even impeachment must conform to standards of fairness and due process.

Still, the ruling is a reprieve, not a vindication. Its basis was technical: Impeachment complaints cannot be initiated more than once against the same official within a one-year period.

For the Duterte camp, the decision shields the vice president from immediate removal. Even failed impeachment efforts carry political costs, forcing allegations into public view and keeping officials on the defensive.

For critics, however, the ruling represents a procedural reset rather than closure. To them, it highlights how difficult it remains to hold powerful figures to account, pointing to a broader accountability gap that courts alone cannot resolve.

Had impeachment proceeded forthwith and resulted in conviction, the vice president would have been permanently barred from public office. With that path closed — for now — her eligibility for a presidential run remains intact.

The court held that impeachment is temporarily barred because a new complaint cannot be filed within one year of a dismissed case. That restriction expires in a matter of days, on Feb. 6, and several activist groups and lawmakers have already signaled their intent to file fresh complaints once the window opens.

Impeachment, however, is only one element of a larger legal picture.

Beyond the High Court ruling, the Duterte family, particularly the vice president, faces a growing list of legal challenges that refuse to fade quietly into the background. Complaints filed before the Office of the Ombudsman allege corruption, plunder and misuse of public funds, most notably involving hundreds of millions of pesos in confidential funds during her time as vice president and as education secretary. Other accusations revisit governance issues from her years as mayor of Davao City.

These matters are criminal in nature, not merely political. While investigations are ongoing and far from final judgment, their potential consequences are significant. Should prosecutors find probable cause, trials could stretch into the pre-campaign and campaign periods of 2028. Even without convictions, the visibility of court proceedings, investigative reports and document disclosures could shape voter perceptions in ways no campaign message can easily counter.

This is where the 2028 election begins to take form, not simply as a contest of personalities, but as a test of accountability.

Supporters of the Dutertes argue that the cases are politically motivated, part of an effort to weaken a still-formidable political force. They cite the Supreme Court ruling as proof that institutions are resisting what they see as partisan pressure, a narrative that resonates with a loyal base wary of elite criticism.

Opponents draw a different conclusion. To them, the combination of a stalled impeachment and unresolved corruption complaints reflects a system strained by dynastic influence. They caution against mistaking procedural victories for moral clearance, noting that the persistence of these cases points to unresolved questions about transparency and public funds use.

For voters, the contrast is stark. On one side stands a potential candidate temporarily insulated from impeachment and backed by a powerful political name. On the other is an expanding list of legal challenges that could come to define not only a campaign, but the state of democratic accountability itself.

The deeper cost of this legal and political struggle is distraction. As Congress and the Office of the Vice President trade legal moves, public attention drifts toward political survival rather than governance. If the next impeachment effort is truly about accountability, it must address the substance of the allegations, not merely procedural compliance.

If it becomes only another instrument of 2028 positioning, the Filipino voter bears the loss, forced to choose between a leader who has yet to answer the merits of the charges and a legislature that struggles to follow its own rules.

The 2028 presidential race is thus already unfolding in courtrooms and commission offices, as much as in rallies and surveys. Whether the legal cases involving the Dutertes advance or stall will shape not only who can run, but also what standards of leadership voters are willing to accept.

In the end, the question is not merely whether Sara Duterte can run in 2028. It is whether the country is prepared to confront the tension between political power and legal accountability, and what it means when the two collide long before a single vote is cast.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.