Text and photos by ELIZABETH LOLARGA

IN a strange way, the logs and trees that came tumbling down when Typhoon Sendong let loose three months’ worth of rainfall in one night on Iligan City were victims of neglect like the flood’s human victims. Sculptor Julie Lluch, who was born and raised in the city, dislikes it when the term “killer logs” is used.

After the retrieval of bodies and relief work, usable logs were stockpiled and commandeered by the city government, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) for the building of new houses. These were cut for lumber and distributed.

Unheeding of superstitious beliefs that the storm’s flotsam was haunted by voices of the flood victims, a curious Lluch and her sister Almita L. Cruz saw potential for art. In February this year, they made countless trips to and from Barangay Saray where logs and debris were beached along a five-kilometer coastline.

They saw many beautifully shaped driftwood. Cruz recalled, “A lot of it was grotesque, but there was beauty in it. Nobody touched them, except to use as firewood. People marked them for firewood on first come, first served basis.”

Barangay Captain Robert Fuentes described the calamity period: “The logs were so many that they looked like they had formed an island.” Some stood 47 feet tall with a width that couldn’t be embraced by four adults.

He discouraged barrio folks from making charcoal out of the debris for selling to lechon makers and showed them what could be done with the tree’s roots as an alternative livelihood from the traditional fishing and broom-making.

His carpentry hobby enabled him to show them how buyers from Manila and Cebu were willing to shell out P35,000 from a sala set made of driftwood. It was an exercise in turning a setback into something positive.

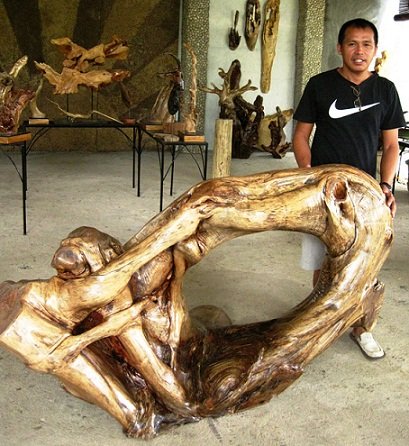

He met the Lluch sisters who were thinking of working along the same lines. The three are part of the show “Debri(s)efing Art: An Exhibit of Found Natural Sculpture” at Lluch’s residence at the Lluch Park Garden in Palao, Iligan City, on view until Oct. 6. Visitors have enthused that the works deserve wider viewing. There are talks of bringing them to Cagayan de Oro City and if a sponsor can be found, to Manila.

Cruz recalled her initial hesitance in getting involved, “I was too busy with rehabilitation, the distribution of food, receiving guests and donors in behalf of my son (Mayor Lawrence Cruz) and taking care of my family. Then I saw these fantastic shapes on the shore.”

In the past, she had gone into plant rentals and the occasional landscape jobs for friends to finance her hobby of collecting plants and making dish gardens. The exhibit was her first time to work with driftwood. She saw it as a way of “sharing with the people what we had seen and preserve it. We didn’t count the costs. This made us see that we can’t move things without people.”

Saving pieces of wood required digging them up and pulling them from the sand. Cruz said a piece jutting out was “like the tip of the iceberg.” When they dug deeper, they found something bigger that took from 10 to 12 persons to carry. These were hauled to Lluch’s open-air garden pavilion by dump truck or by motorized pedicab depending on the size.

Cruz said of the editing process, “I’d look at a piece, follow some principles of bonsai where nothing jars the eyes.” Most of the time the sisters agreed on what to make out of something which explains why the works are unsigned or untitled. Collaboration was the key.

The Lluch sisters, Fuentes and a team of six workers worked with small chain saws, rooters, grinders with different teeth, small sickles, plain saws, sand paper for a good six months. The pieces received a final coating of Tuff Coat to enable them to withstand the elements when exposed outdoors.

The types of wood Lluch only heard from her father and grandfather when they talked about their timber concession business in the old days became visible and palpable to her: apitong, balayong, dao, lauan, tugas.

She said whoever looks at the work sees what he/she wants to see: orchids, sailboats. Fuentes said a particular driftwood seemed like a whale from a distance when he saw it floating in the sea with children riding on it. He pulled it in and turned it into a bench.

Cruz pointed out parts of a driftwood where she saw “violent bruises” from the uprooting and tumbles it went through.

The three all felt elated at what could come out of debris that might have ended up as ashes.