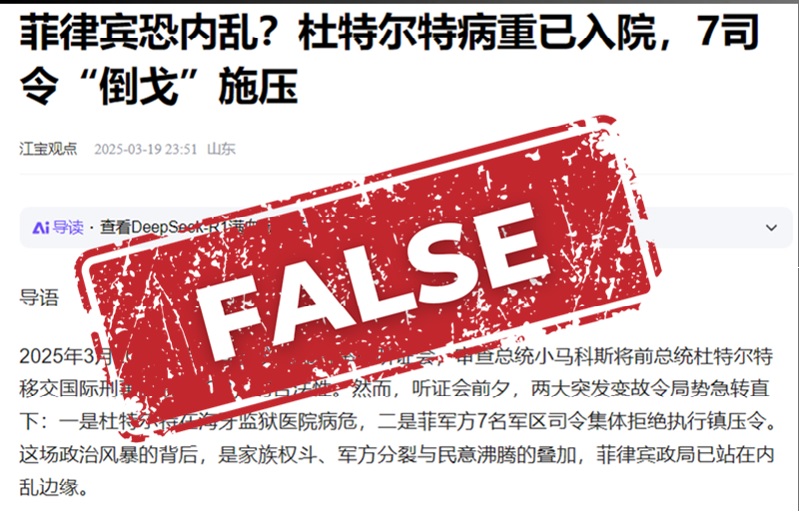

Ten days after his arrest, false reports surfaced on Chinese digital media platforms claiming that former President Rodrigo Duterte had collapsed into a coma while in detention at The Hague, where he faces trial before the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity linked to his bloody anti-drug war.

Fabricated accounts described his condition as dire: critically low blood pressure (80/50 mmHg), erratic heart rate (up to 110 beats per minute), dangerously high blood sugar (328 mg/dL) and signs of kidney failure.

With his life said to be hanging in the balance, Duterte was allegedly rushed to the same detention clinic where former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević “mysteriously” died in 2006 while being tried for crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes committed during the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s. He was reportedly denied proper medication or given “inferior” generic drugs—some allegedly with strong toxic side effects—portraying him as yet another victim of so-called “medical violence,” supposedly like Milošević.

These narratives, laced with military intrigue and civil unrest, have gained traction across China’s information ecosystem. The pro-China Duterte, who turned 80 on March 28, has been recast not as a controversial leader facing justice but as a martyr of Western oppression—with the Marcos administration painted as complicit.

Manipulated media, mass protests, military claims

Agence France-Presse (AFP), a partner of the fact-checking collaboration Tsek.ph, flagged several viral falsehoods circulating on Chinese online platforms after Duterte’s arrest.

One featured a doctored video of Vice President Sara Duterte supposedly defending her father in fluent Mandarin. The footage, originally from her English-language press briefing outside the ICC in The Hague, was dubbed with Mandarin to appeal to pro-Duterte Chinese audiences.

Another false claim alleged that Duterte had urged the ICC to prosecute U.S. and Israeli leaders for alleged war crimes. But during his March 14 appearance before the ICC, he merely confirmed his identity and birthdate. The next stage of proceedings is set for Sept. 23.

AFP also uncovered disinformation using recycled images to falsely depict mass protests backing Duterte or opposing President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.—applying tactics similar to those in the Philippine blogosphere. One video reused a 2015 image from a demonstration held during then President Benigno Aquino III’s final State of the Nation Address, falsely claiming it showed millions of Filipinos demanding Marcos’ resignation. Others misrepresented a January 2025 Iglesia Ni Cristo rally opposing efforts to impeach the vice president and a 2023 antigovernment protest in Warsaw as pro-Duterte demonstrations in Manila.

Additional posts falsely suggested that the military was mobilizing in support of Duterte. One claimed that troops in Davao City threatened to march on Manila and attack the capital, while another alleged soldiers vowed to “slaughter the Marcos family” over his arrest. AFP traced one of the images to 2017, showing Duterte saluting troops after the Marawi siege.

Disinfo highways

AFP found these claims mostly on Weibo, a microblogging platform; video-sharing sites like TikTok, Douyin and Kuaishou; WeChat, a multipurpose app for messaging, social media and payments; and Baijiahao, Baidu’s content platform. Some of the content has also spread to Facebook, X and Threads.

Further research by the author found more claims on other Chinese platforms: Sina, another microblogging platform; Haokan, a short-video platform; Toutiao, Zhihu, Netease and Sohu, which function as content or information hubs. Erroneous reports also appeared on QQ, an instant messaging service and web portal.

False reports about Duterte’s rapid health decline—including the hoax that he had fallen into a coma—circulated on Baijiahao, TikTok, Douyin, Netease, Weibo, Zhihu and even X.

One dramatic account falsely claimed that an ICC judge sneered at Sara Duterte when she attempted to present her father’s medical records, allegedly saying, “Your father is pretending.”

No such exchange took place, but the fabricated quote sparked outrage in Chinese comment sections and was repeatedly cited as evidence of judicial cruelty. In reality, an ICC doctor had found Duterte mentally aware and medically fit during a checkup.

Duterte is detained and marked his 80th birthday at the Scheveningen facility, where Milošević was held from 2001 to 2006 while on trial before the ad hoc International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

The former Yugoslav leader died in his cell. A United Nations inquiry found that his death was due to natural causes, specifically a heart attack, and not the result of murder, poisoning or external violence.

‘Civil war’

As the volume of posts grew, the framing shifted toward open conflict.

The term “civil war” began to recur, with claims that the Philippines was either on the brink of full-scale turmoil or already mired in “small-scale” internal strife.

False narratives of military dissent proliferated. Posts alleged that seven military commanders had “defected,” while others claimed that soldiers had publicly declared they would defy Malacañang, supposedly saying, “Gun barrels do not recognize the President’s order.”

Some Chinese netizens also claimed that guns and ammunition were becoming scarce in the Philippines, with black market prices in Mindanao allegedly tripling overnight.

According to these posts, the rising anger was partly fueled by the Senate’s supposed decision on March 20 declaring Duterte’s arrest legal, and by the Duterte family’s reported decision to “give up the parliamentary struggle.”

In fact, it was officials from the executive branch who told the Senate foreign relations committee—convened by Marcos’ sister, reelectionist senator Imee Marcos—that the arrest was legal.

Senator Marcos later withdrew from the administration’s senatorial slate, Alyansa para sa Bagong Pilipinas, citing Duterte’s arrest. On March 28, she announced that her committee had found “glaring violations” in the handling of the former president’s arrest.

‘Quid pro quo’

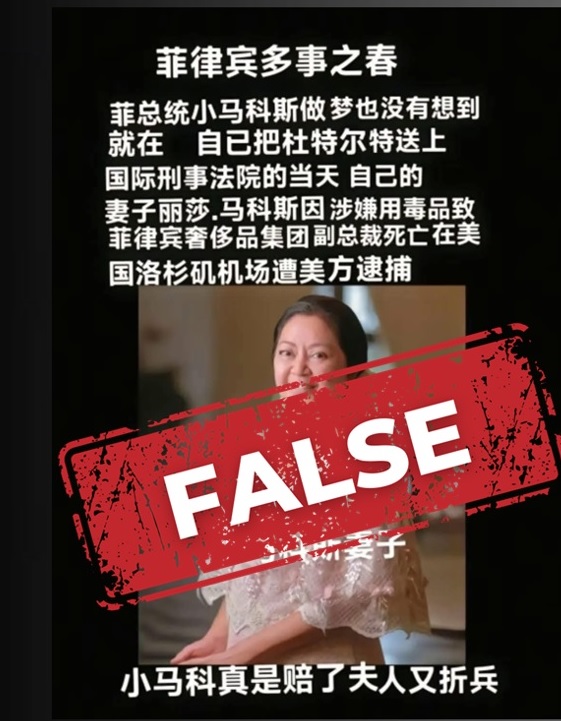

Amid the swirl of Duterte-related disinformation on Chinese digital media platforms, a parallel narrative emerged—this time involving First Lady Liza Marcos.

Unverified claims began circulating not only among Filipinos but also among Chinese netizens, suggesting that Marcos was briefly detained by U.S. customs officers at Los Angeles International Airport on March 11 (other accounts said March 12), the day Duterte was arrested by Interpol.

According to one widely shared post, she was subjected to a humiliating bag search and treated “like a suspect.” Some posts framed the incident under the sensational headline, “First Lady detained for drug-related offenses,” while others linked it to the death of Paolo Tantoco III, an executive of Rustan Commercial Corp., in Los Angeles, California. Tantoco’s wife, Dina, serves as deputy social secretary at the Office of the President.

Malacañang has denied the first lady was held by law enforcers in the U.S., saying she returned to Manila on March 10 after participating in events held in Miami, Florida and Los Angeles, California from March 5 to 8.

Despite official denials, scattered posts about Mrs. Marcos’ alleged detention were woven into a broader theory circulating on Chinese platforms: that the United States had pressured President Marcos into cooperating with the ICC in exchange for “accommodation” in his wife’s case, including possible release or legal leniency.

‘Token of allegiance’

In online discussions, the alleged quid pro quo was also framed as a “token of allegiance.” Under this framing, Duterte—viewed as a longtime China-leaning figure and critic of U.S. military influence—was the price Marcos paid to signal a pivot toward a more openly anti-China foreign policy in return for U.S. support.

The narrative has taken hold in parts of China’s online sphere, where Duterte’s arrest is seen not as justice, but as a strategy allegedly orchestrated by the U.S., with Marcos portrayed as a willing partner.

Strangely, while some posts explicitly accused the U.S. of manipulating both the ICC and the Marcos government to provoke regional conflict and consolidate its global hegemony, others revived former U.S. President Donald Trump’s 2018 speech at the United Nations General Assembly shortly after Duterte’s arrest.

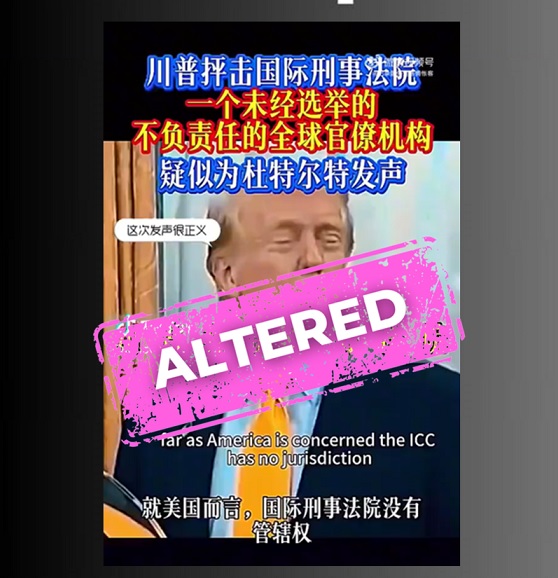

In that speech, Trump criticized the international tribunal, saying, “As far as America is concerned, the ICC has no jurisdiction, no legitimacy and no authority. The ICC claims near-universal jurisdiction over the citizens of every country, violating all principles of justice, fairness and due process. We will never surrender America’s sovereignty to an unelected, unaccountable global bureaucracy.”

Several Chinese accounts inserted the voice clip into an unrelated video of Trump in the Oval Office wearing a yellow tie, falsely presenting it as his reaction to Duterte’s arrest. Trump has not commented on the incident. Footage from his 2018 speech, where the audio was taken, shows he was wearing a red tie.

Countering Sino disinfo

China has enacted a wide-ranging set of laws and administrative measures to curb disinformation, particularly in the online space.

Under China’s Criminal Law, individuals found guilty of spreading false information that disrupts public order or harms reputations may face imprisonment or fines. The law imposes specific penalties for fabricating reports about disasters, epidemics or public security incidents—acts seen as particularly destabilizing.

The Cybersecurity Law and related content regulations require platforms to monitor and remove false or harmful content that may disrupt social stability, with penalties ranging from hefty fines and operational suspension to license revocations.

More recent provisions, including the 2023 deep synthesis regulations, target AI-generated disinformation, mandating clear labeling of synthetic content and enabling criminal charges for deepfakes used in fraud or defamation.

Fact-checking initiatives have also emerged within this ecosystem. For instance, The Paper, a digital publication run by the state-owned Shanghai United Media Group, has also debunked misleading claims of dissent within the Philippine military following Duterte’s arrest.

Despite China’s legal architecture and fact-checking attempts, disinformation continues to thrive across China’s digital landscape.

In a 2022 interview, Jia Qingguo, a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and former dean of Peking University’s School of International Studies, warned that rampant disinformation in China was not only polarizing Chinese public opinion but also fueling tensions between China and other countries.

(Yvonne T. Chua is an associate professor of journalism at the University of the Philippines Diliman and the project coordinator of Tsek.ph.)