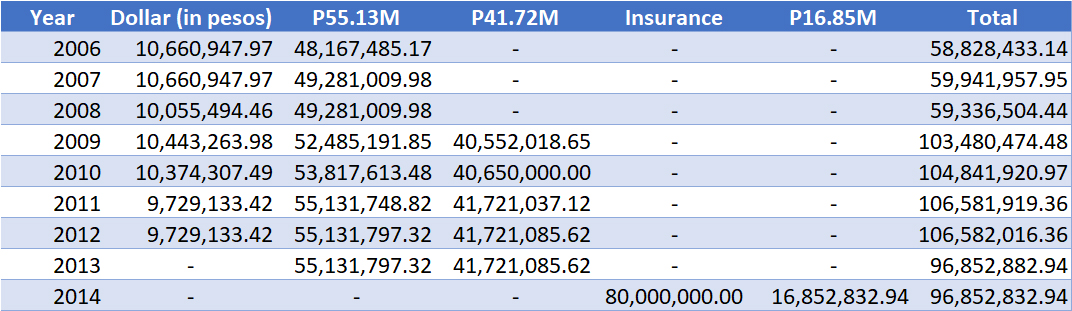

President Rodrigo Duterte and his daughter Sara omitted to fully disclose their joint deposits and investments at the Bank of Philippine Islands, which conservatively exceeded P100 million in some years, when they were mayor and vice mayor of Davao City, our analysis of bank records submitted to Congress and their annual net worth declarations shows.

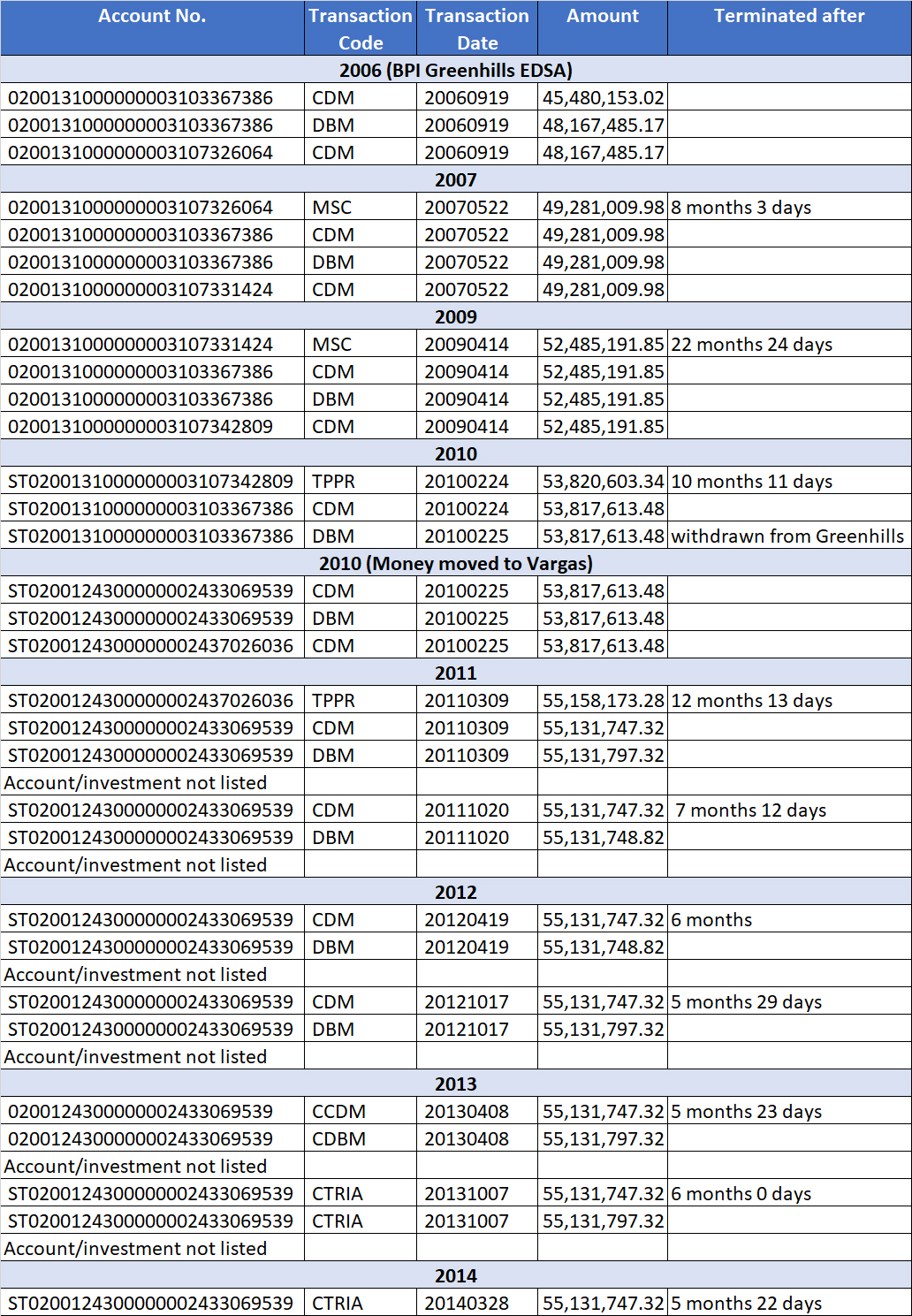

According to the bank records, Duterte and Sara’s transactions with BPI, initially its Greenhills-EDSA branch and later the Julia Vargas branch, included:

- A P48.17 million placement in 2006 that grew to P55.13 million by 2013

- A P40.55 million investment in 2009 that stood at P41.72 million in 2013

- About $220,000, roughly P10 million, from 2006 to 2012

- The purchase of P80 million in insurance policies in 2014

- A P16.85 million investment begun in 2014

The bank records came from the Senate. Sen. Antonio Trillanes IV entered the documents that he said were from the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) into the Senate records on Oct. 3 after delivering a privilege speech saying the president had more than P2.2 billion in questionable bank transactions.

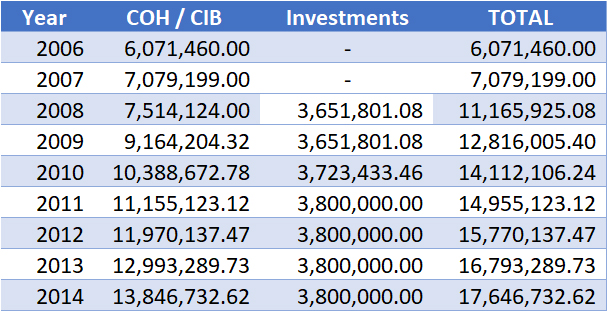

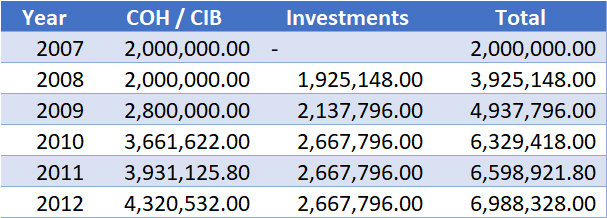

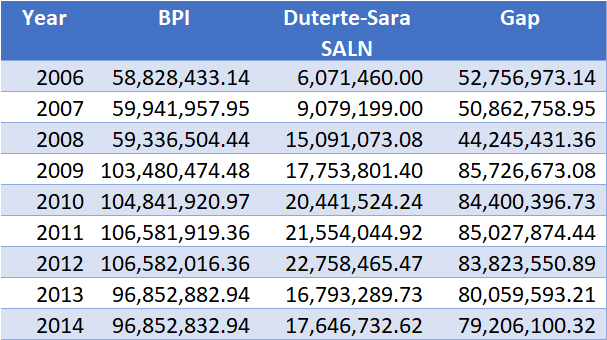

Our analysis shows that the amounts Duterte and Sara listed in their statements of assets, liabilities and net worth (SALN) as cash on hand (COH), cash in bank (CIB) and investments for these years are nowhere near the combined value of their bank transactions as reflected in bank records submitted to the Senate.

Duterte only listed from P6.07 million to P13.85 million a year in cash. He began declaring investments only in 2008, at first P3.65 million and later P3.8 million a year starting in 2011.

Sara’s cash declarations ranged from P2 million to P4.32 million a year from 2007 to 2012. She reported annual investments of from P1.93 million to P2.67 from 2008 to 2012.

What this means: Based on the documents, father and daughter failed to declare from P44.25 million to as much as P85.73 million a year from 2006 to 2014.

For example, when 2011 ended, Duterte and his daughter still had three joint investments totaling P106.58 million, including a dollar placement, according to the bank records. But Duterte only declared P14.96 million in both cash and investments that year and Sara, P6.6 million—a shortfall of P85.03 million.

Republic Act No. 6713, which sets a code of conduct and ethical standards for public officials and employees, imposes a range of punishment from fine to dismissal to imprisonment.

Duterte and Sara’s joint deposits and investments in BPI based on Trillanes’ documents

Duterte’s SALN: Cash and Investments

Sara’s SALN: Cash and Investments

Discrepancy between BPI accounts and SALN

*Sara was not in public office in 2013 and 2014. SALN amounts are only Duterte’s.

Palace, Sara’s response

VERA Files filed on Oct. 23 an official request with the Office of the Senate Secretary for a copy of the bank transactions and was referred to Trillanes’ office. The document was released to VERA Files on Dec. 4.

Malacanang declined to comment on VERA Files’ report, which details for the first time the contents of the alleged bank accounts of the Duterte duo side by side with their declarations in their respective SALNs.

Presidential spokesperson Harry Roque said in an email message on Jan. 18, “We are unable to comment on your story which we believe is hearsay. Bank statements are confidential and hence, the statements on the basis of which your story is written are unauthenticated and hence, unworthy of comment.”

“Furthermore, your story appears to be a rehash of allegations made by Sen. Trillanes since the 2016 elections which until today, remain unsubstantiated,” he said.

Roque added, “We would be happy to comment on your future reports which are based on unassailable facts.”

Sara Duterte said in a statement emailed Jan. 16 to VERA Files, “So that we could all verify the truthfulness of Trillanes’ accusations, we are all waiting for Trillanes to produce his source and put the witness under oath to testify on his/her/their claims about the bank accounts. Anything less than this, what Trillanes is doing is just rumor mongering while hiding behind his parliamentary immunity.”

Duterte has repeatedly said the documents in Trillanes’ possession are falsified.

On Sept. 18, however, he admitted co-owning a bank account with Sara but said it only held P500,000.

On Sept. 30, he said his bank deposits “won’t go beyond P40 million,” or what he called his “life’s savings.” He told soldiers a few days later to “shoot” or “overthrow” him if he had more than the amount.

At around the time, after consistently portraying himself as poor, Duterte suddenly announced he came into his first P3 million when he was a high school senior when he and his siblings sold several parcels of land they inherited from their father.

Days preceding the May 2016 election, Trillanes attached the bank records to the plunder complaint he filed against Duterte with the Office of the Ombudsman. He surmised that part of Duterte’s wealth came from the payroll of ghost employees when he was mayor.

The Commission on Audit, in its 2015 report, questioned Duterte and other city officials for spending close to P708 million the previous year on more than 11,000 contractual workers. The COA, though, stopped short of calling them ghost employees.

Between 2008 and 2015, the number of these workers in Davao City—who also include job order, casual, temporary and coterminous ones—had fluctuated between 6,380 and 11,246, audit reports show. By December 2015, half a year before Duterte bowed out as mayor, contractual workers in Davao City outnumbered regular workers four to one.

Of the 11,000-plus contractual and job-order workers in City Hall, 4,754 were with Duterte’s office. Of the more than P707 million spent on these workers, P376 million, or more than half, was budgeted for programs directly under the mayor’s (Duterte) office, especially for the city’s Peace and Order Program.

The bank records obtained by Trillanes also served as one of the bases for the impeachment complaint filed by Magdalo Rep. Gary Alejano against Duterte. The House dismissed the complaint in May.

AMLC Codes

The Office of the Ombudsman said in late September that a copy of the bank records it obtained from the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) “more or less” resembles what Trillanes submitted in his complaint.

The AMLC, however, denied being the source of Trillanes’ records and providing the Ombudsman any such report.

A source who has knowledge of Trillanes’ and the Ombudsman’s documents told VERA Files that the bank entries found in these records are accurate.

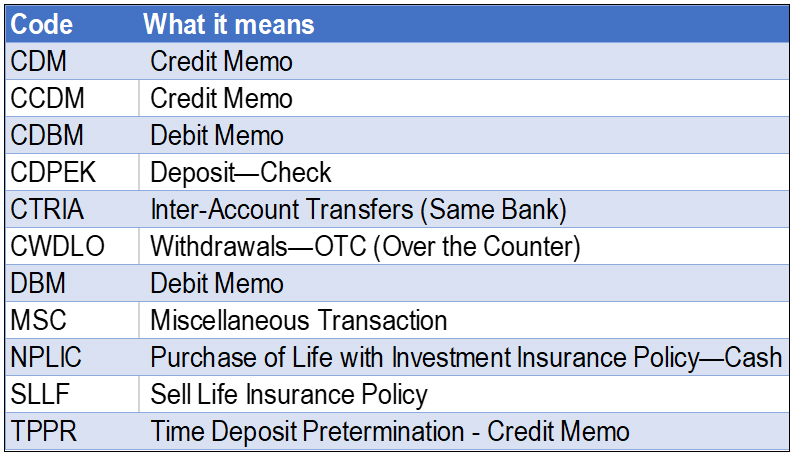

Trillanes’ documents bear transaction codes the AMLC requires banks to use when they report to it “covered” transactions, or those exceeding P500,000 within a banking day.

Generated on April 21, 2016, in the run-up to the election, the senator’s documents list only bank transactions beyond P500,000, or what AMLC would consider as covered transactions. This also means the documents only constitute a partial list of Duterte’s and his family’s bank records.

Besides Duterte and Sara, the documents show the bank transactions of Duterte’s ex-wife Elizabeth and their sons Paolo and Sebastian; Sara’s husband Manases and their children; Paolo’s children: Duterte’s partner Cielito “Honelylet” Avancena and their daughter Veronica.

They show transactions exceeding P500,000 with the following banks: BPI, Banco de Oro, Metrobank, Land Bank, Union Bank, Philippine Savings Bank, East West Bank, Asia United Bank, RCBC, Philippine National Bank, Bank of Commerce and Security Bank.

The transactions also include transfers made from the joint account of Samuel Cang Uy, Samantha Jayne Yenco Uy and Yaneile Yenco Uy to the accounts of Sara, Paolo, Sebastian and Avancena on several occasions. Duterte listed Samuel Uy as one of his campaign donors in 2016. He also identified Uy as the source of a loan between P1 million and P1.2 million in his SALN from 2012 to 2015.

Duterte was mayor of Davao in 2007-2010 and 2013-2016 and vice mayor to his daughter Sara in 2010-2013. Sara was vice mayor in 2007-2010 before being elected Davao City’s first woman mayor in 2010. She chose not to run for public office in 2013, making a comeback in 2016 when her father ran for president.

Like other high-ranking public officials, Duterte and Sara are classified by the Anti-Money Laundering Act, or Republic Act 9160, as “politically exposed persons” or PEP, having been entrusted with a prominent public position in the country “with substantial authority over policy, operations or the use or allocation of government-owned resources.”

As government employees, both of them are mandated by Republic Act 6713, the Code of Conduct for Public Officials and Employees, to file their sworn SALN every April 30 covering their assets, liabilities, business interests and relatives in government the preceding year.

RA 6713’s implementing guidelines require public officials and employees to declare under personal properties their COH, CIB, insurance policies and other investments such as negotiable instruments, securities, stocks and bonds. The amount of cash, on hand and in bank, should be the last balance as of Dec. 31.

For properties co-owned with other individuals, the guidelines require government employees to disclose the proportionate amount of their share in the property.

P55.13M, P41.72M investments

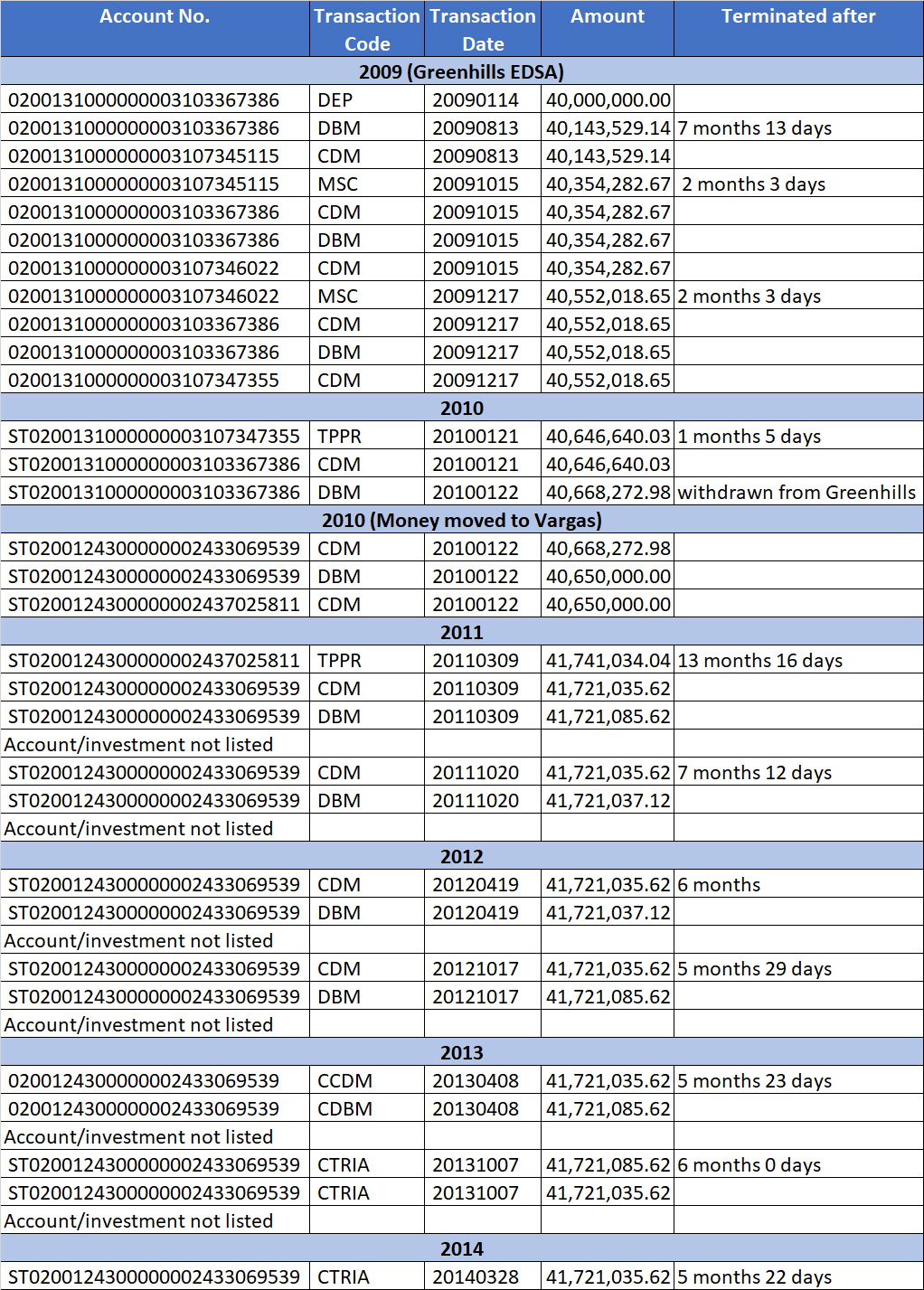

Duterte and his daughter co-owned Account No. 0200131000000003103367386 in BPI Greenhills-EDSA and Account No. ST0200124300000002433069539 in the bank’s Julia Vargas branch, according to documents Trillanes provided the Senate.

The accounts were the source of two huge placements, initially P48.17 million and P40.14 million, in time deposits and later in other unspecified types of investment.

Records show a deposit of P45.48 million made to the Greenhills branch on Sept. 19, 2006. A slightly higher amount, P48.17 million, was withdrawn that day and placed in a time deposit account (No. 0200131000000003107326064). The placement was terminated on May 22, 2007, or more than eight months later, and was deposited back to Account No. 0200131000000003103367386.

This means Duterte should have recorded the deposit as part of his CIB or investment in his 2006 SALN. But he reported only P6.07 million in cash that year.

The same-day transactions would become the pattern for this sum until 2014, even after the Dutertes moved their deposits from Greenhills to Julia Vargas in 2010, an election year. By 2014, this placement had grown to P55.13 million.

The time deposits can be distinguished by their account numbers; they differ from Account No. 0200131000000003103367386 and Account No. ST0200124300000002433069539.

Unlike time deposits, however, other types of investments are not assigned account numbers and thus explains why they do not appear in Trillanes’ documents, according to bankers interviewed for this report.

Banks own subsidiaries or firms that offer a range of investment and insurance products. The unit investment trust fund or UITF is one such product. The bank transfers the client’s money out of his or her savings or checking account to its subsidiary to invest in this instrument (hence, no account number for the investment). The money, or the principal amount, is then deposited back to the client’s bank account when the investment is terminated. The earnings from UITF are deposited separately from the principal amount to the client’s bank account.

P55.13M Investment

Reading AMLC’s Transaction Codes

Duterte and Sara’s Greenhills account reflected a P40 million deposit on Jan. 9, 2009. Over the next five years, they would start investing this in either time deposits or other instruments, similar to what they did with the other placement. They were again characterized by same-day transactions. By March 2014, the placement stood at P41.72 million.

P41.72M Investment

It was in 2011 that the Dutertes began putting both their P55 million and P41 million not in time deposits but in other types of investment where the yields were not included in the principal amounts (P55 million and P41 million) when the placements were terminated. Because the earnings were deposited separately, this explains why the principal amounts appeared stagnant.

Apparently out of convenience, for the Dutertes or the bank, the two placements would be invested or would be terminated on the same dates since they were transferred to the Julia Vargas branch: Jan. 22, 2010; March 9, 2011; Oct. 20, 2011; April 19, 2012; Oct. 17, 2012; April 8, 2013; and Oct. 7, 2013.

Life with investment insurance

The last recorded entry for the two placements in Duterte and Sara’s joint account ST0200124300000002433069539 at BPI Julia Vargas was on March 28, 2014. They added up to P96.85 million.

That day, five same-bank inter-account transfers, which go by the code CTRIA, were reported: four of them each in the amount of P20 million and one in the amount of P16.85 million.

Four days later, on April 1, bank records show the purchase in cash of four life with investment insurance policies from BPI-Philam Life Assurance Corp, each valued at P20 million. Sara, her brothers Paolo and Sebastian and their half-sister Veronica were each issued a policy under their name.

All the policies declared Duterte as the issuer, or owner, as well as the beneficiary, according to the records.

The issuer or owner gets back his or her investment with interest after the policy matures. Should he or she die, the person under whose name the policy was made becomes the beneficiary.

The records do not show a payout of these policies.

Insurance Policies (B = Beneficiary | I = Issuer)

Duterte’s declarations for 2014 did not include the four insurance policies he owned at the time. He only listed P13.85 million in cash and P3.8 million in investments that year.

The SALN guidelines require government employees to declare their insurance policies. Duterte seems to be aware of the rule. His 2008 SALN declared P3.65 million in investments, including P1.3 million in private insurance.

Duterte’s elder son, Paolo, who was elected Davao City’s vice mayor in 2014, also omitted to include the P20 million insurance policy in his SALN that year. His SALN stated he had P6 million in cash and P850,000 in investments.

The former vice mayor did not respond to VERA Files’ request for his side on this issue.

(Three years earlier, one of Sara’s individual accounts showed a deposit of $1 million—P43.42 million at the time—after she sold her life insurance policy with BPI-Philam Life Assurance Corp. Her SALN for 2011 reflected no such proceeds from the sale of the policy; it only showed P3.93 million in cash and P2.67 million in investment.)

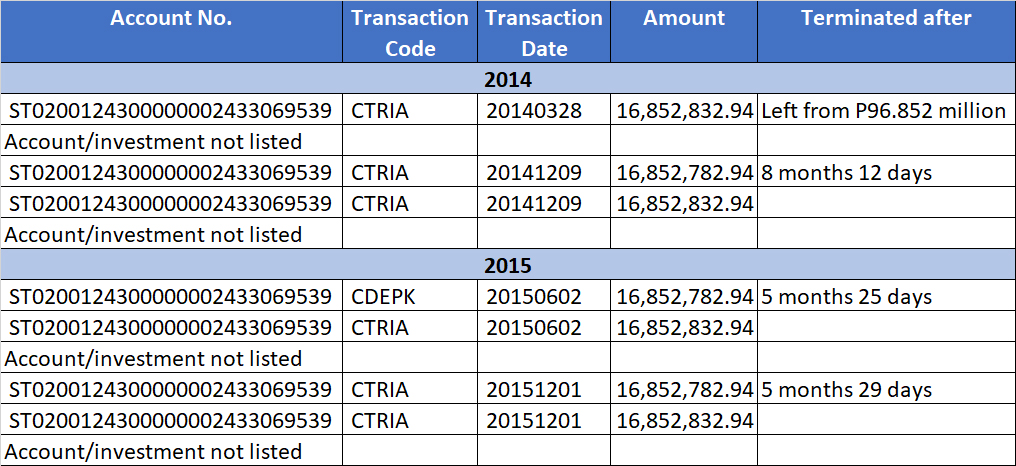

The fifth transaction on March 28, 2014 involved the same-bank transfer of P16.85 million to an investment. Records show the sum was still intact as of Dec. 1, 2015.

P16.85M Investment

Dollar deposit

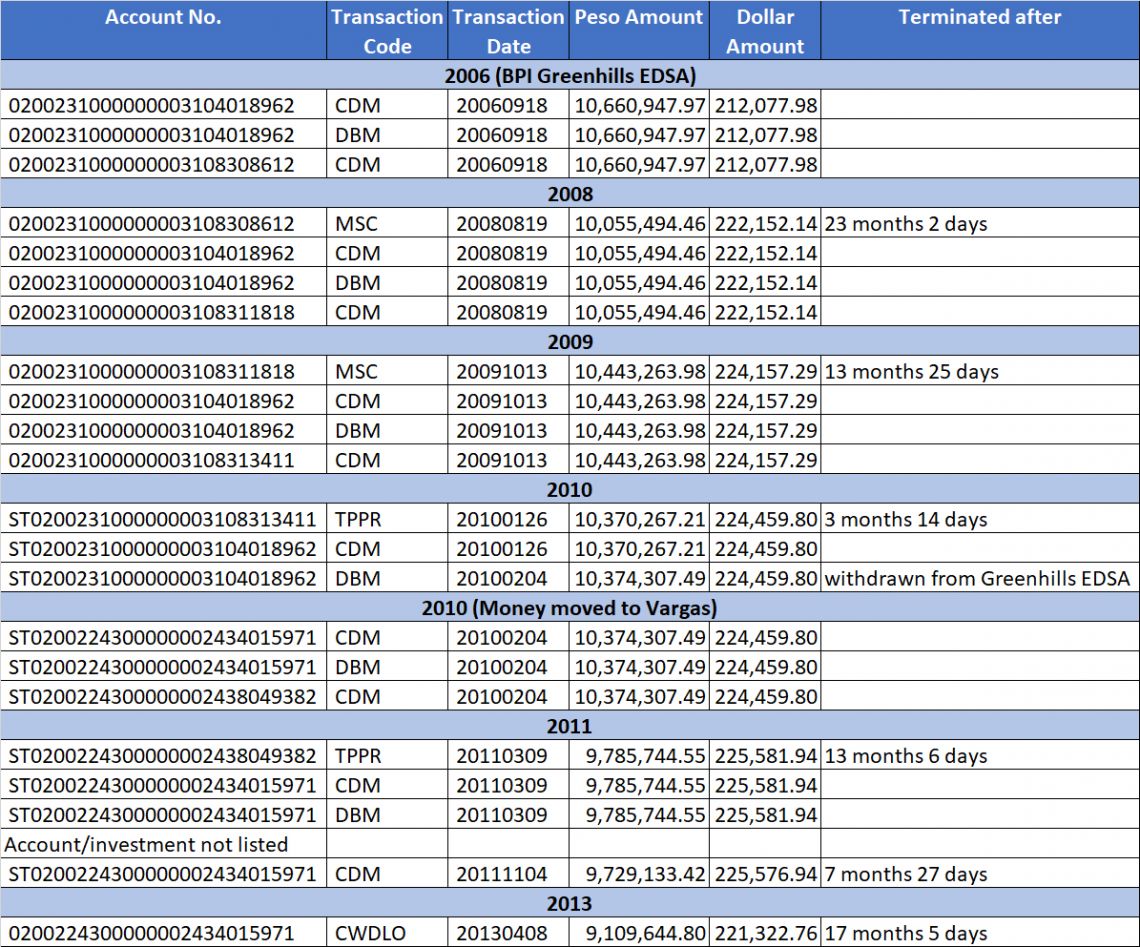

Duterte and his daughter’s joint account No. 0200231000000003104018962 at BPI Greenhills-EDSA held their dollar deposits and investments that stood at $212,077.98 in 2006 and grew to $224,459.80 in 2010.

It was withdrawn that year and transferred also to BPI Julia Vargas (ST0200224300000002434015971) until it was eventually withdrawn over the counter on April 8, 2013.

Dollar Investment

Trillanes’ P2.2B allegations

Trillanes told VERA Files in a letter dated Jan. 16 that the P2.2 billion he alleged was in the Duterte accounts “was the total credits/deposits in various bank accounts of President Duterte from September 2006 to December 2015.”

He said several bankers and accountants reviewed the AMLC documents and observed that credits/deposits exceeding P50 million were made 13 times and those involving P40 million to P50 million were made 21 times. Trillanes’ office computed these at more than P1.5 billion.

Of the P80 million insurance Duterte bought for his four children all on April 1, 2014, Trillanes said, “A person who claims to have only P100 million will not spend almost all of his money for insurance.”

The senator also pointed to “a pattern of periodic credits/deposits” in the Duterte accounts every March and October which he said coincided with the “periodic encashment of checks” during those months of about P10 million each by Sara, Paolo, Sebastian and Avancena from Uy’s account. “It also means that the money in the Duterte accounts is also from Cang Sammy Uy,” he said.

Penalty for omissions in SALN

The penalties for violating the SALN provisions in RA 6713 are imprisonment of up to five years, a fine of up to P5,000 or dismissal from the service.

In 2012, the Senate, sitting as an impeachment court, convicted then Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato Corona, ruling that “his deliberate act of excluding substantial assets from his sworn Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth constitutes a culpable violation of the Constitution.”

The Office of the Ombudsman in 2014 filed criminal and civil cases against Corona before the Sandiganbayan, charging him with perjury and violation of RA 6713 for misdeclarations in his SALN from 2004 to 2010.

The cases were dismissed following his death in 2016.

Over the years, the Office of the Ombudsman has dismissed other government officials and employees and barred them from holding public office for misdeclaring their net worth. It has also filed criminal cases against them before the Sandiganbayan, charging them with grave misconduct, serious dishonesty or falsification of public documents, among others.

The Supreme Court, meanwhile, has affirmed the dismissal from service and forfeiture of retirement benefits of several officials for omissions in their SALN, including a court interpreter and a court sheriff.

Citing RA 6713, the high tribunal said any violation of the SALN provision proven in a proper administrative proceeding is sufficient cause to remove or dismiss a public official or employee, even if no criminal prosecution is instituted against him or her.

Malacanang previously said Duterte is immune from suits while he is president.