The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) will elect its first parliament in May 2025 following the creation of the autonomous state in 2018 through the Bangsamoro Organic Law or Republic Act (R.A.) No. 11054.

The upcoming elections will also see the rollout of the Bangsamoro Electoral Code (BEC) or Bangsamoro Autonomy Act (BAA) No. 35, which lists political dynasties and turncoatism as grounds for disqualification.

“These changes we’re trying to introduce will benefit everyone. We’re simply leveling the playing field [and] we want to have a more inclusive kind of system,” said Bangsamoro Information Office chief Ameen Andrew Alonto.

1. What is the anti-dynasty rule for the BARMM?

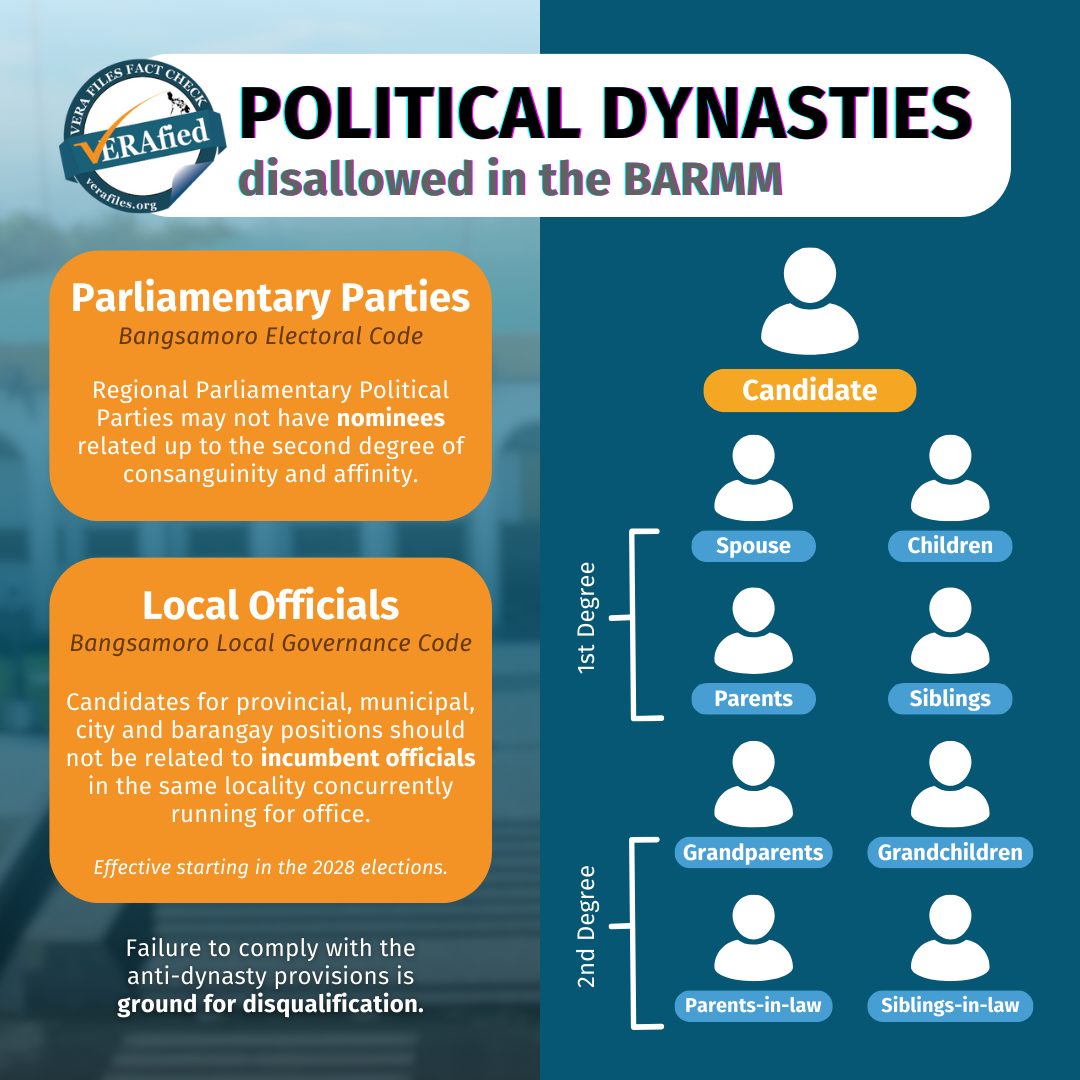

Article III, Section 9 (d) of the BEC prohibits nominees of regional parliamentary political parties (RPPPs) to be related to another within the second degree of consanguinity (relationship by blood) or affinity (relationship by marriage).

This means that RPPPs may not nominate the children, grandchildren, siblings, parents, grandparents, spouses, parents-in-law or children-in-law of their other nominees.

Nominees must submit a sworn statement, along with their certificates of candidacy, confirming that they have no such relatives nominated under the same RPPP. Otherwise, violating nominees should be disqualified in a manner determined by their party.

RPPPs constitute 50% of the 80 parliamentary seats to be filled in the 2025 polls.

The Commission on Elections (Comelec) recognized the anti-dynasty rule in its Resolution No. 10984, issued last April 24, which spells out the implementing rules and regulations on the BEC.

A similar provision exists in Section 45 (g) of the Bangsamoro Local Governance Code (BLGC), or BAA No. 49, passed in September 2023.

Electoral candidates for barangay, municipal, city and provincial positions must not have relatives within the second degree of consanguinity or affinity who are incumbent officials in the same locality running for elective positions.

In such cases, those vying for lower office between relatives will be disqualified. For relatives aspiring for the same position, election authorities will draw lots to determine which candidate can continue.

Both laws will already be implemented in next year’s elections, but the anti-dynasty provision in the BLGC will apply to local officials only starting in the 2028 polls.

2. Is the anti-dynasty measure constitutional?

The 1987 Constitution prohibits political dynasties “as may be defined by law” in Article II, Section 26. However, no law has been passed defining or banning political dynasties for national positions despite the numerous bills filed over the years in Congress.

Some Bangsamoro lawmakers who opposed the regional anti-dynasty provision argued during a Sept. 28, 2023 plenary session that the restriction on political dynasties should be done by Congress and not by the regional parliament.

A group of Bangsamoro leaders filed a petition to the Supreme Court in June 2023 seeking to void the entire BEC due to issues of “encroaching” upon the mandate of Comelec. The anti-dynasty provision was not cited specifically in the petition for nullification.

Alonto said the Bangsamoro government has yet to receive any notice from the High Court restraining the implementation of the BEC. “The parliament is trying to push the envelope in exercising its autonomy,” he said.

Despite opposition among regional lawmakers, experts insist on the constitutionality of the anti-dynasty provision, in particular.

Political science professor Zainal Kulidtod of Mindanao State University said the political autonomy granted by R.A. 11054 means the anti-dynasty provision is well within the BARMM’s legislative mandate.

“The measure is constitutional… the law grants the highest degree of political autonomy [to the BARMM], prescribing such [a] measure is within the jurisdiction of the autonomous region in promoting honest, participatory and peaceful elections,” said Kulidtod.

Former associate justice Adolfo Azcuna shared in an Oct. 7 interview on Teleradyo Serbisyo that policymakers could look to the Bangsamoro provision as an alternative method to prohibit political dynasties if passing a national law proves difficult.

“The Supreme Court can say… the definition [of political dynasties] by law need not be by Congress, that it can be by the president or by the courts, that is possible… [or] by any organ of the state,” Azcuna said.

3. How are political dynasties affecting the region?

The BARMM has had one of the highest concentrations of enduring political dynasties in the country, according to a study by former Ateneo School of Governance (ASOG) dean Ronald Mendoza. In 2013, Maguindanao had the highest concentration of dynastic officials at 64.45% while Lanao del Sur followed with 59.47%.

A 2019 study by the Europe-based think tank Asia Centre and the French General Directorate of International Relations and Strategy pointed out that, in the elections that year, Maguindanao also had the highest concentration of unopposed candidates who were mostly from the same families, which was not unusual for the region.

Read FACT SHEET: What it means to be ‘unopposed’ in the 2022 polls

“Communities in the BARMM are more feudal, [have a] more patron-client relationship than those of Luzon and Visayas… when there is a political dynasty, that will effectively become an affront to free and honest elections,” said Kulidtod.

Another study by Mendoza found that the concentration of power among a handful of families “promote[s] the uneven patterns of development in the Philippines,” especially in areas such as the BARMM, which are more distant from the National Capital Region.

“The isolation of more remote provinces affords political dynasties some measure of insulation from political and economic competition and thereby allows them to consolidate power and ensure their continued survival without necessarily promoting desirable and inclusive economic outcomes,” the study concluded.

The Bangsamoro region previously had the highest poverty incidence in the country at 55.9% in 2018. The rate is now at 23.5% but is still the second poorest in the nation.

Read FACT CHECK: Marcos’ claim on ‘decreased’ poverty index in BARMM needs context

BARMM provinces have also regularly appeared on the Comelec’s list of election hotspots, or areas of concern for election-related violence. For the 2025 polls, 27 of the 38 areas being monitored by the Comelec and the Philippine National Police are located in the BARMM.

Notable cases of election-related violence were also documented in the BARMM, such as the 2009 Ampatuan-orchestrated massacre in Maguindanao that left 58 persons dead, including 32 media workers.

4. To what extent do the provisions address political dynasties in the region?

Given the issue of clan politics in Muslim Mindanao, Kulidtod said the existing provisions are not enough to fully stop political families.

The BLGC entertains only the possibility of reelectionist relatives from the same locality, while the BEC considers only relatives gunning for seats within the same party. Kulidtod pointed out gaps in these provisions that could still allow for relatives, possibly beyond the second degree of consanguinity and affinity, to secure positions.

“What about, for example, the incumbent [graduates] and the son or wife is going to run [for that position instead]? So there is this continuous hold of power within a single family,” he said.

The BARMM is not the first to enact an anti-dynasty provision. In 2016, R.A. 10742 or the Sangguniang Kabataan (SK) Reform Act imposed a similar definition of political dynasties, barring candidates who are related within the second degree of consanguinity and affinity to incumbent officials in the same locality.

See Konsehal, kapitan, kagawad… Kapamilya?

A 2021 ASOG study found that dynastic SK officials decreased by 0.4% in Cebu City, 2.5% in Davao City and 7% in Quezon City from 2010 to 2018 as a result of the law. The researchers also pointed to similar issues of loopholes due to the law’s definition of dynasties.

Despite these concerns, one advantage the BEC and BLGC hold over the SK Reform Act is the penalties for dynastic relations.

The SK Act lists the lack of relations as a qualification, while the BEC and BLGC define it as grounds for disqualification. Election lawyer Emil Marañon III pointed out in 2018 that such a distinction was needed for election authorities to have the power to cancel a candidate’s registration.

Technicalities aside, the people of Bangsamoro nonetheless look to the existence of the anti-dynasty provisions as a signal of change.

Based on voter education drives and consultations done by the Bangsamoro Information Office, Alonto said voters have welcomed the policies so far.

“We have to understand that the Bangsamoro is a result of a peace negotiation, and the election itself is a continuation of the peace process. [It] reflects the desire, the changes that [people] want to see in the exercise of self-determination here in the region,” he said.