In the quiet coastal village of Victory in Bolinao, Pangasinan, in the West Philippine Sea, fishing has sustained the livelihood of coastal communities for generations. It used to take just a few hours for fishermen to fill their small boats with abundant catch. But in the past years, the sea has changed.

“Nowadays, even if we spend the whole day at sea, we come home with barely half a bucket. Our catch is dwindling year after year,” Zaldy Caampued, a member of the Samahan ng Maliliit na Mangingisda sa Victory (SMMV), says in Filipino.

Bolinao lies within the Coral Triangle, a vital marine region spanning the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Timor-Leste, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. Known as the “Amazon of the Seas”, it harbors more than 600 coral species and is home to over one million people who depend on these resources for their livelihoods, according to the Asian Development Bank.

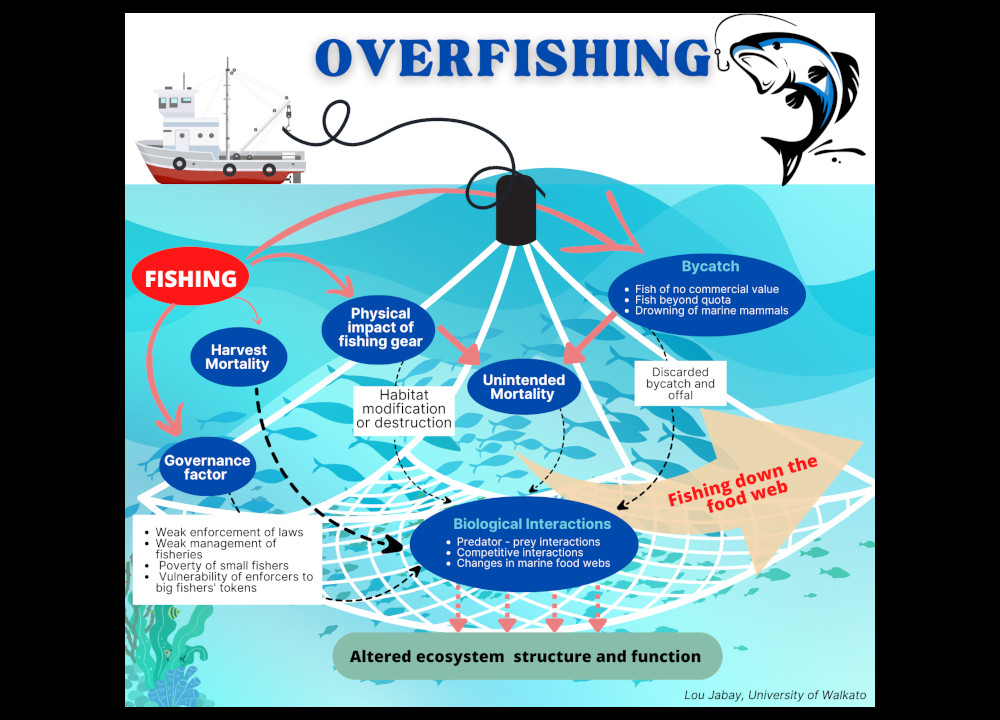

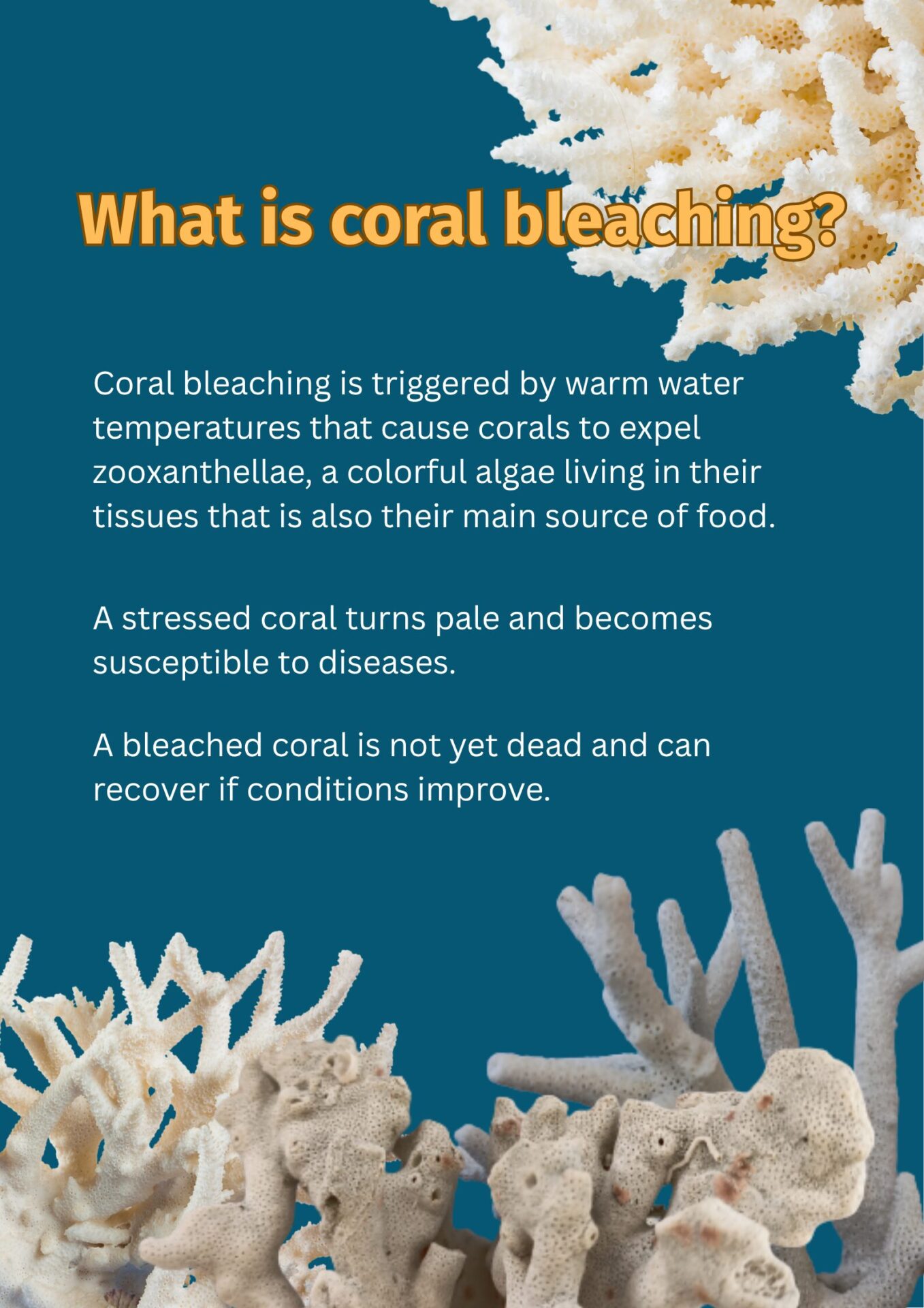

This underwater treasure is now under threat from unsustainable and destructive methods of fishing, such as dynamite and cyanide fishing, and coral bleaching, which have damaged large swaths of reef ecosystems across the region.

For coastal communities in the Philippines like Caampued’s, the decline of coral reefs has meant more than environmental loss. It has changed their way of life.

When fish catches began to drop, the fishermen’s group shifted to sea cucumber and seaweed farming with the assistance of the Bolinao local government and the University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute (UP MSI). Women and the youth have also played key roles in organizing coastal clean-ups.

In fact, seven bantay-dagat (sea wardens) take turns guarding a sea cucumber ranch from illegal fishers.

Decades ago, sea cucumbers were abundant in the waters of Victory. Back then, the Philippines was one of the top producers of dried sea cucumbers in Southeast Asia, producing more than 4,000 metric tons per year in the 70s and 80s. Production has since declined to around 1,000 metric tons in recent years.

Today, the SMMV has to go on 24-hour shifts to ensure that their sea cucumber ranch remains untouched by looters. They are on a mission to restore the once glorious sea cucumber population on the island.

“The shift hasn’t been easy, as many fishers initially resisted abandoning fishing. But as they saw the changes, like healthier corals and the return of small fish, they began to believe,” says Caampued in Filipino.

The five-hectare ranch was established in 2007 with the help of the UP MSI Sea Cucumber Research Program and the support of the local government.

Scientists from the lab nurture juvenile sea cucumbers called sandfish (Holothuria scabra) and deliver them to the sea ranch, where the community members monitor their growth. According to the bantay dagat, it can take over two years for sea cucumbers to fully mature.

But neighboring fishers will sometimes poach premature sea cucumbers and sell them to exporters. A kilo fetches up to P6,500 (around $110), depending on their size.

Sea cucumbers, even the undersized ones, are highly coveted in China, Japan, and South Korea as a delicacy and for their medicinal value.

No easy task

Monitoring the sea ranch comes with its own share of challenges. For one, the ranch is in the open sea, so juvenile sea cucumbers can sometimes swim away from the loose enclosure.

There’s also the lack of proper zoning markers, making it easy for poachers and unassuming fishers to harvest the sea cucumbers.

Confronting poachers presents another challenge: they frequently loot at night. The looters’ boats also have no identifying marks, so the bantay dagat find it difficult to trace and report the theft to local authorities.

Although some looters have already been apprehended by the fisherfolk, others still repeatedly try to poach sea cucumbers from the ranch. Hence, the presence of the bantay dagat is needed.

Though honorable, the work of these sea wardens does not exactly fill the stomach. They earn 300 pesos (around $5) for 24 hours of work. Under the previous mayor, the bantay dagat collectively received a P10,000 incentive, a practice that has since been suspended.

To supplement their income, they fish during the hot season and plant crops when the rains come.

To help limit looting, the local government recently signed an ordinance making it illegal to harvest and trade sea cucumbers that are less than 320 grams, the approximate weight of a fully mature sea cucumber.

“Marami nang makikitang sea cucumber kaya nakikinabang na ang community. Sana pagdating ng araw makikita pa ng mga kabataan ang sea cucumber at ang tulong nito sa corals. We hope to conserve [kung] ano meron ngayon,” said Robert Corbillon, president of the SMMV. “Nagtatanim din kami ng bakawan mangrove, may fish sanctuary, kung mapangalagaan yan, dadami po isda.”

(There are a lot of sea cucumbers now, so our community can now use them. In the future, we hope that the youth can still see the sea cucumbers and their help with corals.)

(We also plant mangroves, so there is a fish sanctuary.)

Charly Feria, a member of the Bolinao Coastal Resources Management Office, said that Bolinao Mayor Jesus “Boying” Celeste has plans to develop the sea ranch as a tourist site, which can bring an additional source of income for the bantay dagat.

Still, there is much to be done to support the SMMV. And it starts with the small things.

Earlier in July, the bantay dagat’s floating house, which they use to keep themselves comfortable and protected against the elements, was swept away by typhoon Emong.

They’re still in talks with the local government to have it replaced.

A connected ecosystem

Sea cucumbers are part of a wider marine ecosystem — one that relies on the well-being of each other to survive and thrive in waters that are becoming increasingly warmer.

As detritivores or waste eaters, sea cucumbers consume tiny waste particles, like plankton, on the seafloor, where disease-causing pathogens are sometimes found.

This act of “cleaning up” is said to help coral reefs stay healthy, with a study suggesting that corals are more likely to contract diseases in the absence of sea cucumbers.

Besides sea cucumbers, the fisherfolk also noted that fish stocks have decreased. The prevalent use of cyanide in the past has pushed them to venture farther out into the sea to catch fish.

They are also aware of the changes that global warming has brought to their environment, especially the nearby reefs.

Corbillon said, “Sabi nga, isang isda, pitong mangingisda ang naghahabol.” (Seven fishermen are trying to catch one fish).

He notes that while the use of cyanide in the area has not been completely eradicated, the local government has taken steps to control the destructive practice.

Dr. Wilfred John Santiañez, an Associate Professor at the Marine Phycology Lab of the UP MSI, adds that the seaweed in Santiago Island used to be bountiful.

“It used to be a very productive area, diverse na area in terms of seaweeds”, he describes, adding that sediments from coastal development and mariculture feed have turned the waters turbid.

Coral reefs ‘already degraded’

Destructive fishing practices also contribute to the poor condition of coral reefs in Bolinao.

Rhea Luciano, a marine biologist working at the Bolinao Marine Laboratory (BML) of the UP MSI, admits that corals in Bolinao are already degraded.

“A lot of people used dynamite here before, so the coral reef cover was almost wiped out. Only a few remain,” she laments in Filipino.

Rising sea temperatures, coupled with destructive fishing practices, overwhelm coral reefs to the extent that recovery is no longer possible.

She explains that the corals’ growth rate is weak and that the continuous stress makes it hard for them to recover. According to Luciano, some corals grow one millimeter or less per year.

A bleached coral is not yet dead, though it’s considered stressed and thus, more vulnerable to diseases. And while recovery is possible, it can take years for a coral — and an entire ecosystem — to heal.

The long road to recovery and restoration

Coral researchers in the BML focus on coral restoration and transplantation to reinvigorate the degraded reefs of Bolinao. This process involves spawning corals in the hatchery, fertilizing, growing, and re-planting them in the reef.

“Ang ginagawa namin dito nagpapa-itlog kami ng corals, mostly branching corals, Acropora. Then, pinag-aralan ng mga researcher namin dito kung saan sila madaling kumapit. So gumawa kami ng mga substrate,” explains Julio Curiano Jr., an administrative staff from the UP MSI.

(What we do is we breed corals, mostly branching corals, Acropora. Then, our researchers study where they can latch on easily, so we make our own substrate.)

A key part of the process is the use of substrates like tocks to encourage coral growth.

Tocks are circular pieces of cement with a plastic attached to it. Substrates like tocks provide stability for young corals, facilitating better growth in the wild.

Earlier this year, the UP MSI established the Philippines’ first coral larvae cryobank facility in the BML to conserve coral reef biodiversity through cryopreservation. The project involves freezing coral larvae to preserve them, as a preventive measure in the event that certain coral species in the wild die off.

Research institutions from the Philippines, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand are working together to establish the first regional network of coral larval cryobank in the Coral Triangle.

For the future

Bolinao is a first-class municipality where a majority of barangays are coastal and rely on cultivating fish and other fishery products. It is bound by seagrass, mangroves, corals, and reefs, with the highest concentration of seagrass beds and corals found in Santiago Island, where Victory is located.

Besides aquaculture and mariculture, residents also engage in small-scale cottage industries, salt-making, bagoong-making, and shell craft, among others. Protecting the population of sea cucumbers and corals is vital to their future.

What keeps fisherfolk like the bantay dagat going?

“Our wish is simple: we want to grow the sea cucumber population so the whole community can benefit from it,” says Caampued in Filipino.

Protecting the ‘Amazon of the Sea’

Across the Philippines, bantay dagat and maritime police are on the lookout for illegal fishing practices, which often slip through unguarded waters.

This, and other factors, make marine conservation efforts in the Philippines a tough nut to crack.

A recent report by ocean advocacy nonprofit Oceana highlighted that fish stocks in the Philippines are declining due to illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities.

Commercial and municipal fishing production peaked in 2010, but has since been on the decline.

Atty. Liza Osorio, Oceana Philippines’ Senior Director for Campaigns, Legal, and Policy, notes that IUU fishing activities are one of the primary threats to coral reefs in the Philippines, along with climate change and pollution.

Lack of funding, lack of data

What makes the task of protecting the marine environment difficult is the lack of data, funding, and support to uphold existing environmental laws and policies.

Osorio notes, “In my almost three decades of experience, I could see the peaks and dips of community-based efforts. It also depends sometimes on our environmental governance framework, where every three years the mayor is replaced.”

This frequent change in governance is another reason why it can be difficult to quell destructive fishing practices, especially when it has been perpetrated for years.

Santiañez, from UP MSI, comments on the situation in Bolinao: “At the end of the day, whatever good science that you produce, whatever good law that you make, if you can’t manage the people, nothing will change.”

Marine scientists and advocates also face another challenge: lack of data. Accounting for the current state of marine biodiversity is important for measuring the extent of loss in marine habitats. But it can be a costly and labor-intensive process.

Mark Joseph Laceste, an Ambassador for the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security, confirms that getting baseline data is a Herculean task.

Laceste is the founder of Lalakabayin Ecoventures, an ecotourism marketplace that engages the youth and conducts conservation tours around Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in Coron, Palawan.

Revenue generated by the tours is reinvested into the MPAs and is used to fund biophysical assessments that measure the health of coastal habitats in the area. This aids the local community and helps identify which conservation projects are most needed.

Still, more support is needed for scientists and marine advocates. Laceste and Santiañez both lament the lack of funding available for their research and projects.

Laceste, who frequently works with youth leaders and women fisherfolk, notes that if they had funding, they would spend more energy on building the program, rather than thinking of how to sustain it.

Meanwhile, Santiañez is spearheading a project on the Ulva seaweed, also known as sea lettuce. Ulva, which is abundant across the Philippines, can be used as a food ingredient, an additive to animal feeds, and a fertilizer.

Guardians of the reef

“‘Yung long-term vision namin na while also protecting our sensitive habitats, coral reefs, mangroves, we will also look at the socioeconomic aspects of the issue,” said Osorio.

She believes that using a bibingka approach (cooking with fire on top and in the bottom), where both the national and local governments work and support projects together, is the key to ensuring the proper implementation of environmental policies.

Protecting critical ecosystems and habitats isn’t just for the preservation of biodiversity – it’s also a way forward to better disaster risk reduction.

On the shores of the Philippines, small coastal communities like Victory are showing that protecting it begins not just with grand policies, but with the hands of those who depend on it most.

“Now that we are part of the conservation effort to protect the ocean, we’re not just teaching the youth on how to protect the ocean, but showing them that we are also guardians of the reef,” said SMMV member Mike Tugade.

(This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network)