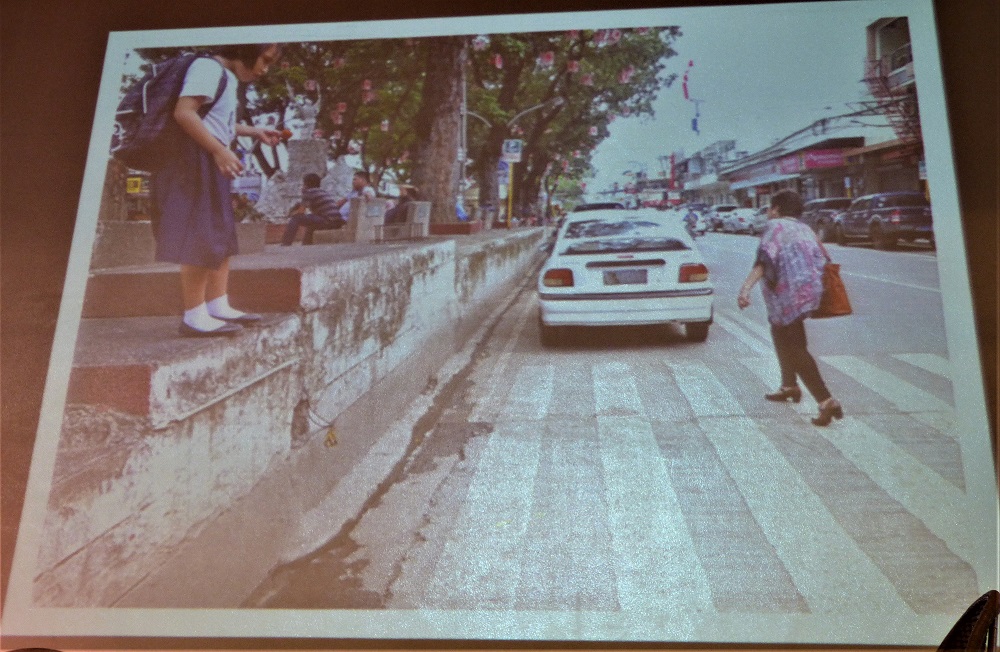

A student prepares to jump from a wall onto a street. Photo by Paulo Alcazaren.

One of the highlights of travelling to places like Japan or Europe is the walking tour.

Whether it’s strolling through a national park or going through city streets to eat at a famous restaurant, pedestrians in developed cities generally have an easy (and fun) time getting to where they need to go.

But in Metro Manila and other major Philippine cities, pedestrians, including children, often dance with death. Whether they are crossing the street or just playing outside their homes, kids are vulnerable.

The Department of Transportation (DOTr), citing the Philippine Statistics Authority, said in a March 2019 statement that four people a day, from 0 to 19 years old, die on the roads nationwide.

Indeed, East Avenue Medical Center Emergency Head Dr. Willie Saludares told VERA Files that most of their patients involved in road incidents are children.

“Ito iyong mga bata na naglalaro sa kalsada na walang nagbabantay na adult (These are the children playing in the streets without adult supervision,)” he said.

Very few of their patients are (private) vehicle passengers, he added. “Madalas sila iyong mga nakasakay sa mga bus o jeep na walang specific o identified na seat para sa mga bata (It’s usually those who ride a bus or jeep without specific or identified seats for children).”

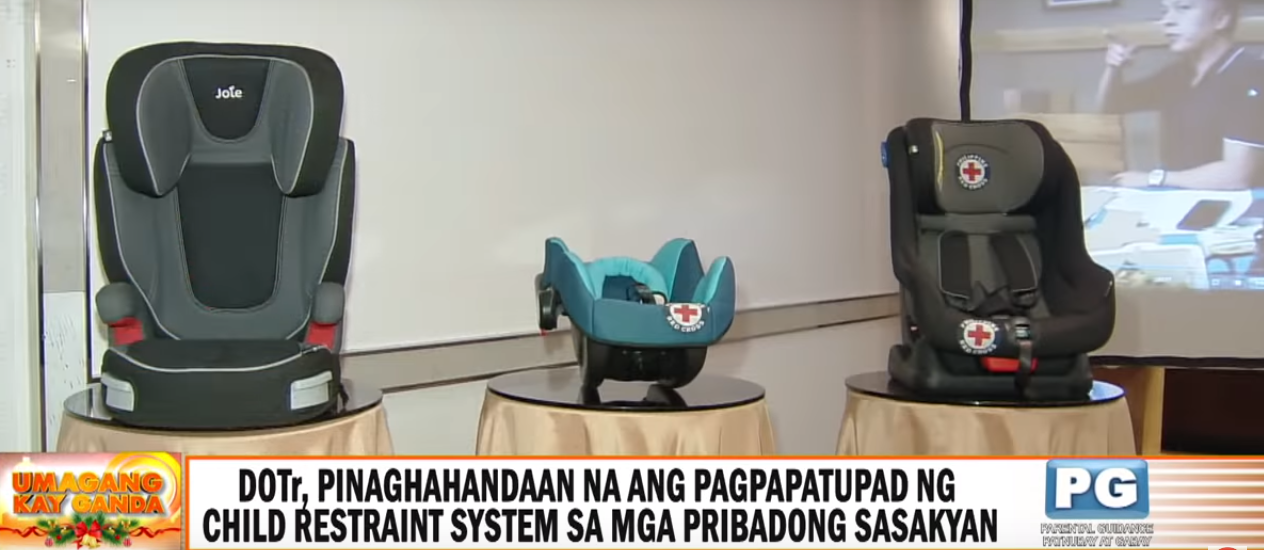

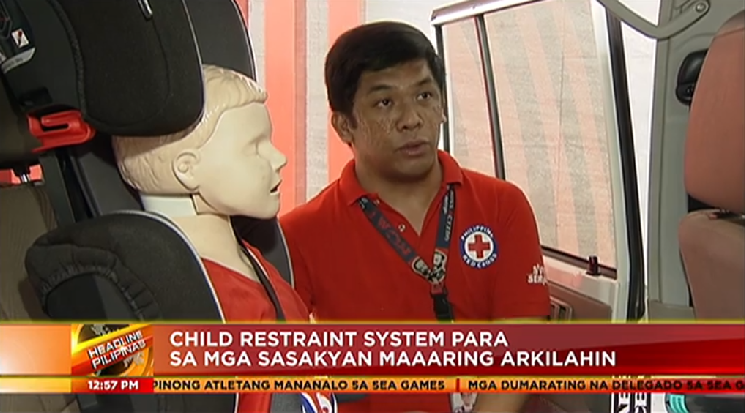

The recently signed Child Safety in Motor Vehicles Law or RA11229, which mandates private vehicle owners to strap children in car seats while travelling, is precisely what’s needed to protect kids.

The law requires the use of child restraints on children 12 years and below to protect them from injury during a crash or sudden stop. These are car seats, booster seats or car beds designed to diminish the risk of injury to a child because they limit a child’s mobility.

Under the law, no child 12 years and below shall be allowed to sit in a front seat unless the child meets the height requirement of at least 150 centimeters (4’11”) and is properly secured using the regular seat belt.

The World Health Organization (WHO) said in its 2018 Global Status Report on Road Safety that road-traffic incidents are now the top killer of people aged 5 to 29 globally, with four in five road-traffic deaths around the world in 2016 coming from middle-income countries like the Philippines.

An earlier WHO report released 2015 showed road crashes were the main killer for only one age group, young adults aged 15-29 years old.

Dr John Juliard Go, WHO Philippines National Professional Officer for non-communicable diseases, has said that the rise could be due to children becoming more exposed to increasingly dangerous roads.

“Children can be passengers and pedestrians. They might have been more exposed to roads, that is why the situation worsened,” he said in a forum in December. “Safety measures taken were not enough to protect them from the dangers on the road,” he added.

Mean streets, meaner drivers

Veteran architect Paulo Alcazaren, principal of environmental planning and urban design firm PGAA Creative Design, said part of the problem is poor road design.

“Sight lines on our roads are terrible. The configurations of our intersections are terrible,” he said in a March 23 forum at the University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P;) in Pasig City.

Architect Alcazaren says the problem is poor road design.

“If you look at every section of the city and you are a civil engineer or a highway engineer, you will see maybe 10 or 15 violations of the (government) code because no one’s answerable,” he added. “You can point it out, but no one will say ‘It’s my fault.’ Who’s to take the blame?”

Citing the International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP), the WHO said 88 percent of pedestrian travel worldwide is on one-to-two-star roads.

iRAP uses a five-star rating system, with a one-star road having no sidewalk, no bicycle paths, no motorcycle lanes and no safe crossings. By contrast, a five-star road has usable sidewalks, dedicated bicycle paths and motorcycle lanes, and crossings with signal lighting.

“For pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists, the lack of specific infrastructure features that can ensure them a safe journey leaves them vulnerable to injury,” the WHO said. “The aim is to create a safe road environment, rather than placing the main responsibility for safety on users who fail to deal with the intrinsic dangers of the roads.”

Alcazaren also noted how Filipino drivers tend to think that they rule the road.

“If pedestrians were given equal importance in public space and the drivers recognize that, then we won’t get run over,” he said. “In other countries, when you step on a pedestrian crosswalk, by law, any vehicle has to stop. Not so in the Philippines. They will increase their speed and try to run over you because they think they have the right of way.”

The WHO also noted that out of the 10,012 Filipinos killed annually in road-traffic deaths, around 100 were pedestrians.

Pedestrians are people, too

Alcazaren said addressing this issue must start with looking at walking differently.

“Everyone walks in a ‘woke’ city,” he said. “Every commute starts and ends with walking and that is the most-neglected part of the transport system. Most infrastructure and the taxes that we pay government goes to infrastructure for cars, not for people. As commuters, because we have no sidewalks, we have to fight with vehicles for our space in this world.”

Alcazaren said pedestrians in other countries don’t need to fight with anyone. “In other cities, we have paradise for pedestrians. Because in other cities, they recognize that pedestrians are actually people.”

Road congestion in the Philippines is only a symptom of a wider problem, he said.

“There seems to be a lack of coordination between the city engineers or a lack of common sense,” he said. “Unless we build a comprehensive and integrated transport system that includes people, then we will always have traffic.”

Simple solutions possible

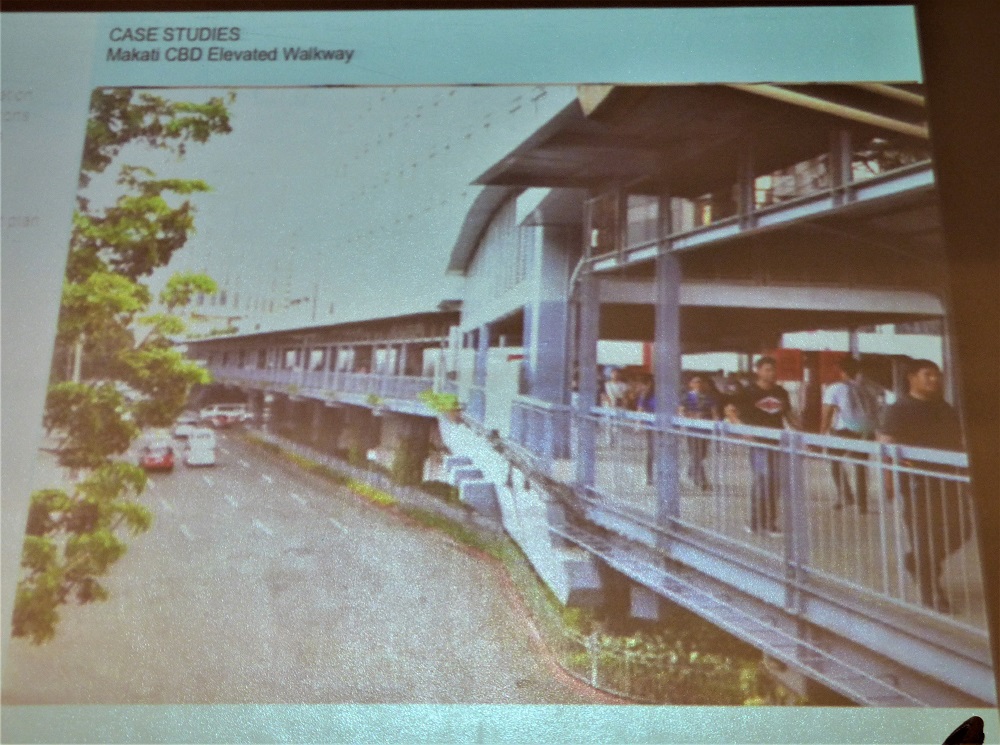

A walkway can make walking in the metropolis safer. Photo by Paulo Alcazaren.

A walkway can make walking in the metropolis safer. Photo by Paulo Alcazaren.

Alcazaren showed some solutions that his firm created to make walking in Metro Manila safer.

One of these is the elevated walkways in Jupiter Street in Makati City, which allow pedestrians to easily go from building to building.

Also in Jupiter Street are urban patios that shorten the distance that pedestrians need to walk to cross the road, without slowing down vehicles.

Alcazaren said his firm has submitted a plan for an elevated covered walkway that would allow MRT-3 commuters to safely get from EDSA to the inner parts of Pasig City.

A joint project between the Asian Development Bank, the DOTr and Pasig City, the proposed walkway would be built on the northbound side of EDSA, running from EDSA Shrine to SM Megamall.

“This has been approved, the drawings are complete, but it got stuck at DOTr. I have no idea why,” he said.

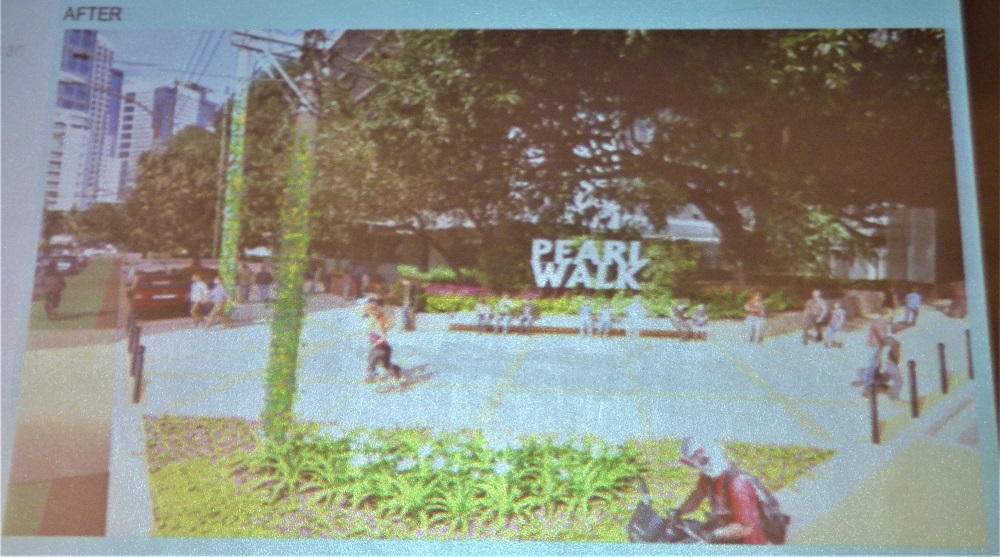

Polishing the Pearl

Stakeholders of The Pearl Project talk about the challenges of the initiative, as well as future developments.

In another part of Pasig City, one community has banded together to take back their street.

Called ‘The Pearl Project’after a major road in the city, the initiative calls on the city government and the Ortigas group to rehabilitate Pearl Drive by removing sidewalk obstructions like parked cars.

This is an ideal setup for pedestrians who need not dance with death while walking. Photo by Paulo Alcazaren.

The move is being spearheaded by the Friends of Pearl Drive, which is composed of residents of Barangay San Antonio, as well as students and faculty of UA&P;, which is located on that street.

“Pearl Drive should be for its people, but the actual built environment tells us that people are unimportant on Pearl Drive,” said UA&P; professor Philip Peckson at the forum.

“What is important on Pearl are people with cars,” he added. “For the convenience of these few, everyone else has to walk on the road or are endangered or inconvenienced, even on the sidewalk.”

Alcazaren said his firm is working on what could be considered an extension of The Pearl Project, which aims to create safe, green and walkable spaces for residents, including children, by redesigning sidewalks and alleyways, as well as vehicle parking spaces.

“It’s not complicated once you have seen how things will work, once you have seen these other best case scenarios and stories of success here in the Philippines,” Alcazaren said. —VERA Files Reporter Klaire Ting contributed to this report.

This story has been produced with the help of a grant from The Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP), a hosted project of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).