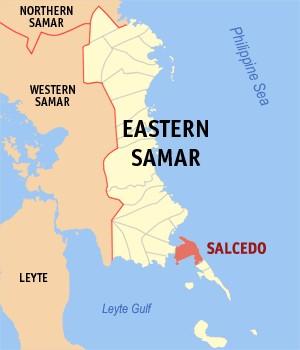

SALCEDO, Eastern Samar — Along the Pacific coast, where storms rewrite the shoreline each year, this town is trying something unusual: confronting climate change not only with sandbags and evacuation drills, but also with data, local knowledge and a growing demand for accountability.

Two years ago, Salcedo became the first municipality in the Philippines to pass a local resolution calling for the accountability of major fossil fuel companies for climate-related losses. At the time, some observers dismissed it as symbolic. Yet local leaders, residents and now youth groups argue that symbols sometimes mark turning points, especially in places where rebuilding has long been a cycle rather than a phase.

Today, the youth of Eastern Samar are amplifying that call. Their urgency reflects a long pattern of loss—now increasingly supported by scientific evidence.

The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) and climate researchers report sea levels in Eastern Visayas rising 4.5–5 millimeters annually, contributing to more frequent coastal flooding and intensified storm surges that threaten homes and livelihood.

This story examines what the resolution has (and hasn’t) changed, how local evidence is being built, and where tensions lie between resilience, accountability and long-term adaptation.

A community tested by storms

Between late 2023 and early 2024, a string of storms caused almost ₱469 million in infrastructure damage across Samar provinces. Salcedo’s geography—36 of its 41 barangays along the Pacific coast—places much of the municipality directly in the path of shear line disturbances and typhoons.

Last Nov. 9, PAGASA issued an unusually blunt warning of a “high risk of life-threatening storm surge” for Eastern Samar. For many residents, the phrasing confirmed what they have long known but rarely see acknowledged with such urgency.

Storm debris, washed-out roads, breached seawalls and losses in fisheries and crops have become cyclical. Severe Tropical Storm Kristine (international name: Trami) alone caused ₱16 million in fisheries damage in October 2024, affecting over 2, 000 small fisherfolk. More recent typhoons—Tino (Kalmaegi) and Uwan (Fung-wong)—left behind landslides, damaged homes and silted rivers.

In a Nov. 8 article for Greenpeace, Eastern Samar advocate and Yolanda (Haiyan) survivor Ronan Renz Napoto described the emotional residue of each landfall: “Every new typhoon reopens the wounds of the last. We hammer nails into our roofs while shaking in fear, pack our bags while holding back tears, and cling to our neighbors as we pray the floodwaters don’t rise again.”

Local officials say these narratives are no longer anecdotal; they are data points.

The Resolution: symbolic, strategic, or both?

Salcedo’s 2023 Municipal Resolution on Climate Accountability was the first in the Philippines to formally name major fossil fuel companies and recognize their contribution to climate risks experienced locally. The resolution does not impose penalties; instead, it lays groundwork for possible future claims or participation in global accountability efforts.

Legal experts interviewed emphasize limits and possibilities: Local resolutions cannot trigger liability on their own, but they can document harm, signal intent and support future climate finance or litigation.

Adding an international perspective, Avril De Torres, deputy executive director of the Center for Energy, Ecology, and Development (CEED), said when interviewed on Nov. 22:

“Our climate realities demand that the Philippine government champion not only compensations for loss and damages, but also the formulation of a global roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels as a matter of survival.”

Salcedo’s municipal resolution aligns with this global need for accountability and just transition measures for vulnerable communities.

Some national agencies consider the measure forward-looking. Others privately characterize it as “largely symbolic,” raising questions about what symbols can achieve in a community repeatedly forced to rebuild.

For fisherfolk like 58-year-old Ricardo Cabael, the meaning is more literal than legal. “Our families cannot keep rebuilding with our own bare hands. Every time the water rises, we start from zero,” he said, recalling how he and his wife dry their few remaining belongings on higher ground after each evacuation. Yet he also admits something more complicated: “We rebuild because we want to stay here. This is home.”

His words capture a tension shared by many residents, a conflict between love for a place and fear of what staying means in the long term.

Youth voices: urgent, assertive, not entirely aligned

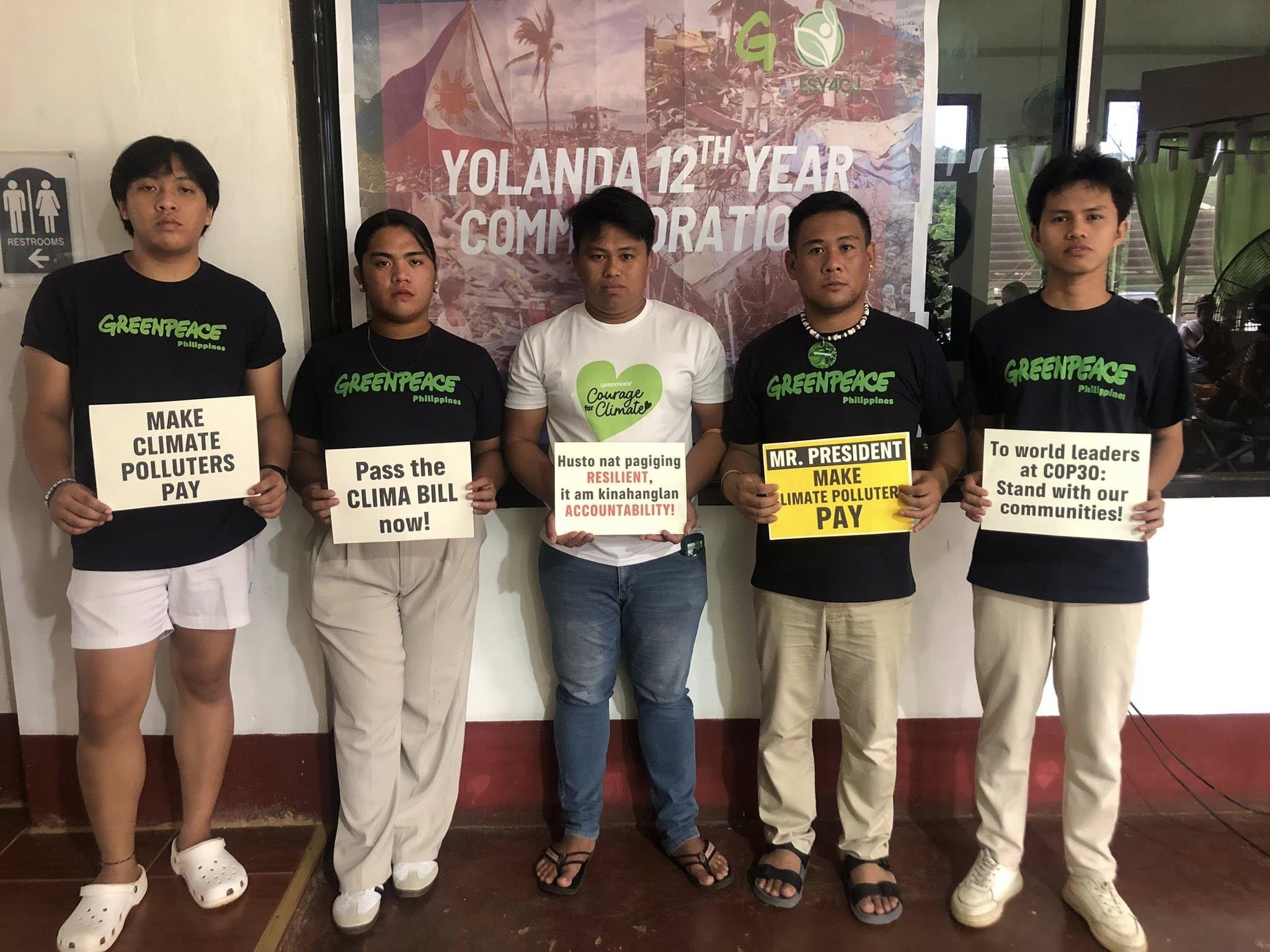

On Nov. 20, youth volunteers from Greenpeace Philippines – Eastern Samar and the Eastern Samar Youth for Climate Justice released a manifesto declaring, “We stand together in a unified and urgent demand: Climate justice now.”

For the people of Salcedo, a fifth-class municipality with more than 22,000 residents, this is not rhetoric. It is the lived experience of communities forced to rebuild repeatedly in an era of worsening storms.

For them, “justice” is not only about compensation but also about understanding where responsibility lies, how solutions can be implemented, and what communities can realistically expect in a future of stronger storms.

“For those of us on the frontlines, climate justice is not charity; it’s accountability,” said Napoto.

One student leader admitted in an interview: “We don’t always know the right path. Some of us worry we’re asking for too much; others fear we’re asking for too little.”

This internal conflict—hope mixed with doubt—is part of the narrative often missing in climate discussions. It reveals a generation not only protesting, but grappling with the complexity of a global problem that they inherited.

The manifesto cites recent Oxfam data, supported by global inequality studies, showing that one person from the richest 0.1% emits more carbon in a day than the poorest half of the world emits in a year.

The manifesto also expressed support for ongoing lawsuits filed by survivors of Super Typhoon Odette (Rai, December 2021), arguing: “Those most responsible must finally pay their long-overdue debt.”

A movement still taking shape

Beyond rhetoric, youth activists are working on the ground, documenting local impacts, organizing mangrove plantings and participating in disaster risk education. But interviews show differences in emphasis: some focus on accountability and systemic responsibility, others prioritize adaptation and community education while a few emphasize economic survival and job security as equally urgent.

CNT-aligned coverage surfaces these divergences: the climate crisis is one shared experience, but not a single narrative.

Youth activism in Salcedo has been steadily increasing. The Sudao Generation Ready for Environmental Education and Action (GREEN) Minds, founded in 2019, now has around 50 active members who conduct coastal cleanups, mangrove planting, and climate education drives.

“They’re not just volunteers,” one municipal officer said. “They’re the next generation who will inherit whatever is left of our shores.”

Youth groups in Salcedo—Sudao G.R.E.E.N. Minds, Eastern Samar Youth for Climate Justice, Greenpeace volunteers—now play dual roles as community organizers and informal data gatherers, providing testimonies and mapping storm impacts.

They also join local officials in advocating for access to the People’s Survival Fund and the Loss and Damage Fund. Some youth leaders caution that without safeguards, such funds risk being absorbed by bureaucracies before reaching vulnerable households

Mangroves, maps and the limits of resilience

On Nov. 23, multiple youth groups joined local government units, NGOs, and residents in planting mangroves at the Seguinon Fish Sanctuary.

According to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, mature mangrove belts can reduce wave energy by 60–80%, making them one of the most effective natural barriers for communities like Salcedo.

The town has also developed a Disaster Risk Management Map Book, working with local and international partners to map displacement risks and design community-based adaptation measures. The youth emphasize: adaptation cannot replace accountability.

“People call that resilience,” Napoto said. “But to us, it’s survival, and survival shouldn’t have to be this hard.”

But residents and volunteers offer varied interpretations of such initiatives. For some officials, mangroves are a cost-effective protective measure. For the youth volunteers, they are both mitigation and symbolic. For older fisherfolk, mangroves help but do not solve declining catch or increasingly unpredictable seas.

These differences are not contradictions; they reflect lived experience under uncertainty.

Building an evidence base: Inside Salcedo’s data room

Two years after passing the landmark resolution, Salcedo is assembling a GPS-tagged archive of storm damage: photos, cost estimates, fisherfolk logs, crop losses, testimonies, and barangay-level hazard maps.

A municipal staff member explained: “We want evidence that cannot be ignored.”

The archive serves multiple functions: disaster risk reduction management planning, climate-finance applications, infrastructure redesign and potential future legal claims.

International precedents, such as climate litigation involving TotalEnergies in France and community cases in the Global South, are being reviewed by Salcedo’s legal advisers. Whether such pathways become viable for the town is still uncertain.

In a Nov. 22 statement, Avril De Torres of the Center for Energy, Ecology, and Development (CEED) called for stronger global commitments: “We find hope in the recognition of the urgent need to address the interlinked global crises of climate change, biodiversity loss and land and ocean degradation, as well as the vital importance of protecting, conserving, restoring and sustainably using terrestrial and marine ecosystems for effective climate action.”

She added a note of urgency, “We cannot afford to walk away from Belem with anything less,” referring to the 2025 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30), which took place in Belém, Brazil, from Nov. 10–21.

Her remarks connect Salcedo’s local experience with broader debates at UN climate negotiations—where loss and damage funding, just transitions, and ecosystem protection remain contentious.

Breaking, not repeating, the cycle

Twelve years after Yolanda, and two years after the climate accountability resolution, Salcedo stands at a convergence of pressures: stronger storms, rising seas, fragile livelihoods, limited local resources and a desire to pursue justice without losing sight of practical adaptation needs.

The youth manifesto concludes: “We speak now as survivors, advocates, and bearers of responsibility for the future we will inherit.”

“May this year mark not another cycle, but the breaking of one,” Napoto said.

Salcedo’s ongoing work—data gathering, legal exploration, community-led mitigation, and youth mobilization—suggests that the town is moving beyond declarations. But whether these efforts will shift outcomes, secure funding, or influence accountability mechanisms remains an open question.

What is clear is that Salcedo is no longer speaking alone.

*Ricky J. Bautista, publisher/editor of media startup Samar Chronicle, is a VERA Files fellow under the project Climate Reporting: Turning Adversities into Constructive Opportunities.

This story was produced with the support of International Media Support and the Digital Democracy Initiative, a project funded by the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

The views and opinions expressed in this piece are the sole responsibility of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, and International Media Support.