The Grand Mosque stands tall despite the beating it took during the five-month battle.

MARAWI CITY – Barefoot children screamed in glee as they played tag on the one-lane road. The adults huddled in one side, exchanging bits of gossip and looking on curiously at local government officials who came to visit their community in Sagonsogan Village.

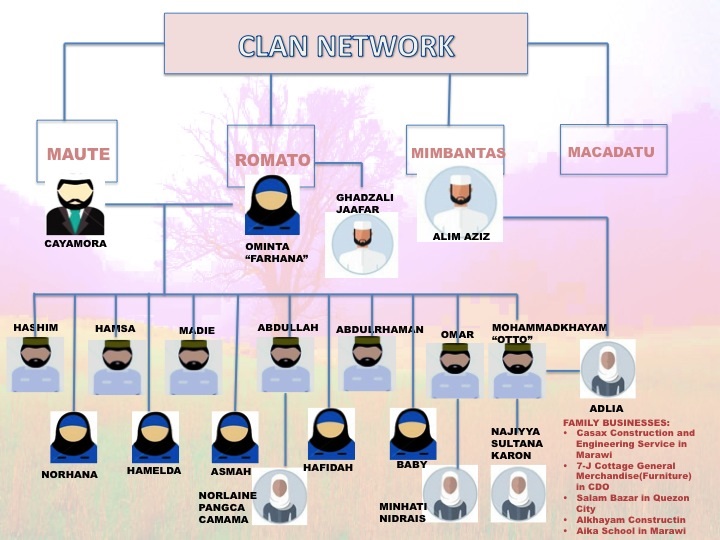

The settlement is a grid of 1,052 units of nearly identical 22-square meter houses. It is one of the three sites constructed to accommodate some of families displaced from Marawi’s business district, which bore the brunt of the fighting between government troops and the ISIS-linked Maute Group that began on May 23, 2017 and went on for the next five months.

The fighting killed over 1,000 people and displaced close to as many as 100,000.

The once-bustling district, now called Ground Zero because it had been reduced to rubble, still harbors the danger of unexploded bombs and ordnances.

Mosera Laot, 33 years old, was able to get a unit at the housing settlement just in April.

“At least now, I’ll have my own space,” she said, noting

that it would be her first time to manage her own household even though she is

married and a mother to four young children.

Before the Marawi siege, Laot lived with her parents and siblings in a four-storey house in the Marawi business district. That house is now leveled to the ground.

Her parents and the rest of the family moved to their second house in Cagayan de Oro City but Laot decided to stay in here where she is employed by the city’s social welfare office.She and her neighbors are among the fortunate few to have been granted temporary housing.

Sadness, anger and despair fill the empty streets of Marawi.

So far, Task Force Bangon Marawi has completed the construction of 1,608 shelters of the target 6,852 units. This target excludes the homes already or are being built by private organizations and business enterprises meant for the 15,700 people who remain displaced in the aftermath of the fighting in the Islamic city.

They are the residents within the 2,560-hectare district now designated as the Most Affected Area (MAA) in Marawi. This is where the Maute hunkered down in an attempt to claim Marawi City – the only Islamic city in predominantly Catholic Philippines – as part of ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) territory in Southeast Asia.

“People are frustrated,” Marawi mayor Majul Gandamra acknowledged, but explains that his people understand the complexity and magnitude of the task of rebuilding lives and the city.

Prior to the siege, MAA had been crammed with a motley of entrepreneurs and traders, their businesses spilling over into streets jammed with vehicles.

After Marawi was liberated in October 2017, the only vehicles seen were those of the military personnel tasked to keep civilians out. The walls of buildings were either pockmarked with bullet holes or were blown away entirely, leaving the foundations of structures exposed.

Vegetation has started reclaiming this part of the city, giving a post-apocalyptic vibe to the once vibrant neighborhood.So far, Task Force Bangon Marawi has completed the construction of 1,608 shelters of the target 6,852 units. This target excludes the homes already or are being built by private organizations and business enterprises meant for the 15,700 people who remain displaced in the aftermath of the fighting in the Islamic city.

They are the residents within the 2,560-hectare district now designated as the Most Affected Area (MAA) in Marawi. This is where the Maute hunkered down in an attempt to claim Marawi City – the only Islamic city in predominantly Catholic Philippines – as part of ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) territory in Southeast Asia.

“People are frustrated,” Marawi mayor Majul Gandamra acknowledged, but explains that his people understand the complexity and magnitude of the task of rebuilding lives and the city.

Prior to the siege, MAA had been crammed with a motley of entrepreneurs and traders, their businesses spilling over into streets jammed with vehicles.

After Marawi was liberated in October 2017, the only vehicles seen were those of the military personnel tasked to keep civilians out. The walls of buildings were either pockmarked with bullet holes or were blown away entirely, leaving the foundations of structures exposed.

Vegetation has started reclaiming this part of the city, giving a post-apocalyptic vibe to the once vibrant neighborhood.

Marawi seige survivor Jamil Pangundaman :Restarting life from zero

Sitting atop a hill overlooking the placid Lanao Lake is the Grand Mosque, which wasn’t spared from the heavy bombardment during the war. Engineers checked on the integrity of the remaining structures of the place of worship and declared the building need not be torn down.

Other structures are not as lucky.

Private contractor Eddmari Construction has begun tearing down and leveling structures cleared of explosives. However, there are several structures with a sign indicating that their owners have not given consent.

Gandamra said these structures are those with deep sentimental value to owners or have questions of ownership or whose owners have not secured a proper title to the property.

A committee that will include respected community leaders will be organized to help sort out the matter of ownership. Until then, the structures will remain untouched.

Eduardo del Rosario, a retired Army general and head of the Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council, said that 90 percent of the MAA has been cleared of unexploded ordnance and that 25 percent of that area has been cleared of structures.

The demolition work would have been quicker if they had the residents’ full cooperation early on, he said.

Clearing of the area is scheduled to finish by the end of November although reconstruction has already begun.

Work has started on public infrastructure such as the Banggolo Bridge and the district’s main road,which will be expanded to four lanes. Additional highways will also be constructed to link the city to other urban centers in the province.

Private property, however, will not receive government funds for their reconstruction.

“Private owners will have to rebuild their own houses. We can allow them beginning July,” del Rosario said.

Until then, Marawi residents who lost their homes will have to make the most of the current set-up.

K-9 units working under private contractor Eddmari Construction make a second sweep of the grounds to ensure that no unexploded ordnance remains buried.

Some 1,800 families provided with temporary shelters are given another two to three years years to rebuild their homes in the MAA before they have to leave the housing project.

The bigger number of evacuees – 11,400 families – are living with relatives.

Montisah Sani, 31 years old, was among the hundreds who went to the City Hall on the second anniversary of the Marawi siege to find out exactly how she could apply for temporary housing.

Her family is currently sharing the house of a relative with five other families in nearby Baloi town.

“We’ve lived with so many relatives and we’ll have to move to another one soon. It’s hard for them to be supporting so many of us for too long,” Sani said.

Sixty-two year old Malika Aruba Domato is also living with 19 others in a relative’s house, and is disappointed that those living in evacuation centers are being given priority when it comes to the government-provided shelters.

“But what can we do? We just wait for Allah to provide,” mused Domato, who has resumed buying and selling small trinkets as a business.

But there are some who are setting their sights on a possible future elsewhere.

Jamil Pangundaman is one of them. Right now he is forced to cram his wife, four children, and two small grandchildren into the temporary shelter in Sagonsongan because they lost their home and his tricycle – his only means of livelihood – during the fighting.

“Now I just take someone else’s tricycle out from time to time,” he said as he carried his granddaughter in his arms.

Pangundaman is now looking into the possibility of working outside Marawi, but would prefer to instead be provided the resources to restart his life in the city of his birth. He said the war pushed their life “back to zero.”

But he is not giving up. “Give us funds and we can restart

our lives,” he said.

Cassava grows on the ruins of what was once the busiest and most vibrant district in Marawi City.