“Imelda Marcos’s nephew funds Harvard’s new Tagalog language course,” went the headline of The FilAm’s August 29, 2023 exclusive story on House Speaker Ferdinand Martin Gomez Romualdez’s $1 million secret donation to Harvard University. Which, as pointed out by Carmela Fonbuena of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, “amounts to around 10% of his declared total net worth as of 2016.”

At the end of The FilAm article it was mentioned that “in 1981, the Philippine government tried to donate money—also $1 million—to endow an academic chair at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy to be named the Ferdinand E. Marcos Chair for East Asian and Pacific Studies. The pledge for the donation was withdrawn after critical editorials and reporting in U.S. newspapers. As reported in the Harvard Crimson, citing sources at the Fletcher School, ‘Marcos withdrew the funds because he was dissatisfied with his treatment by both Tufts and the U.S. government.’”

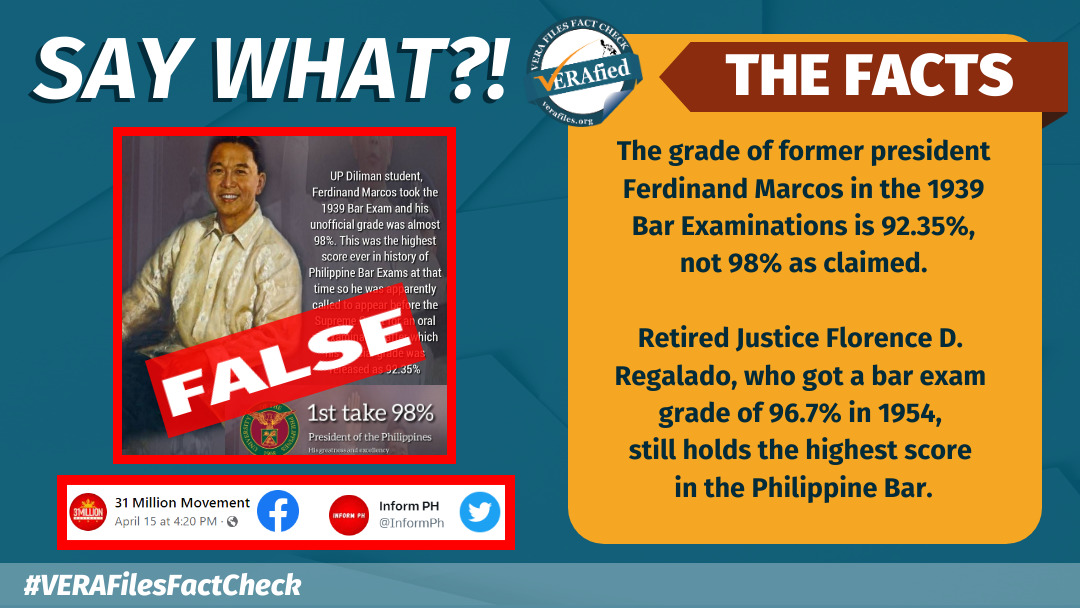

The FilAm erred on this part. It was in 1977 and not 1981. The endowment pledged to Tufts University was $1.5 million. It was not the Philippine government that made the commitment; it was the Marcos Foundation. And “tried to donate” simply fails to capture the ill intent of the parties involved in setting up the Chair of East Asian and Pacific Affairs.

In the “Official Month in Review” of the Official Gazette (vol. 73, no. 15) , the entry for February 1, 1977 reads: “The President referred to the board of trustees of the Marcos Foundation a proposal to set up a chair at the prestigious Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University in Medford, Mass., US. The proposal was submitted to the President by Nihal W. Goonewardene, a Sri-Lankan who is directing the school’s Asia Pacific teaching fellowship program based in Manila.”

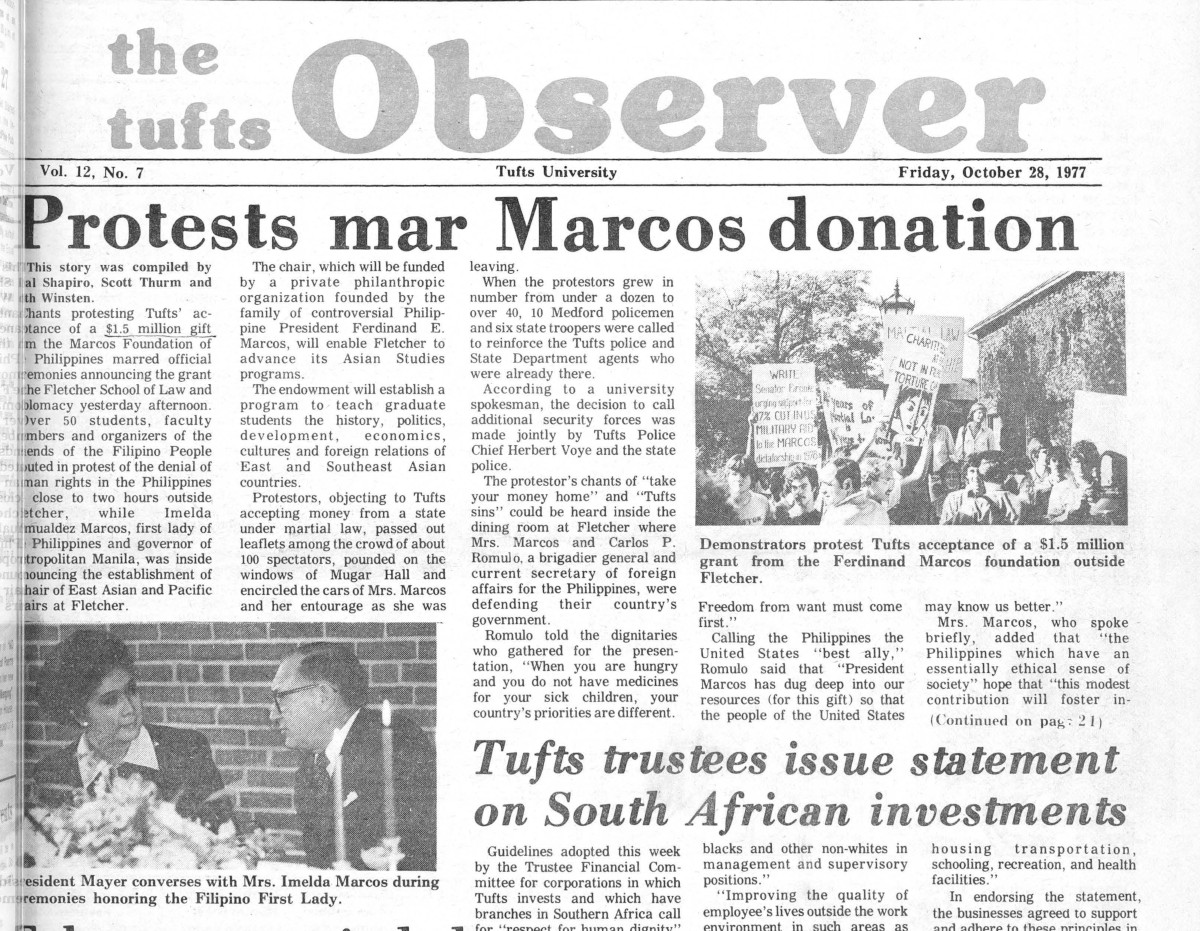

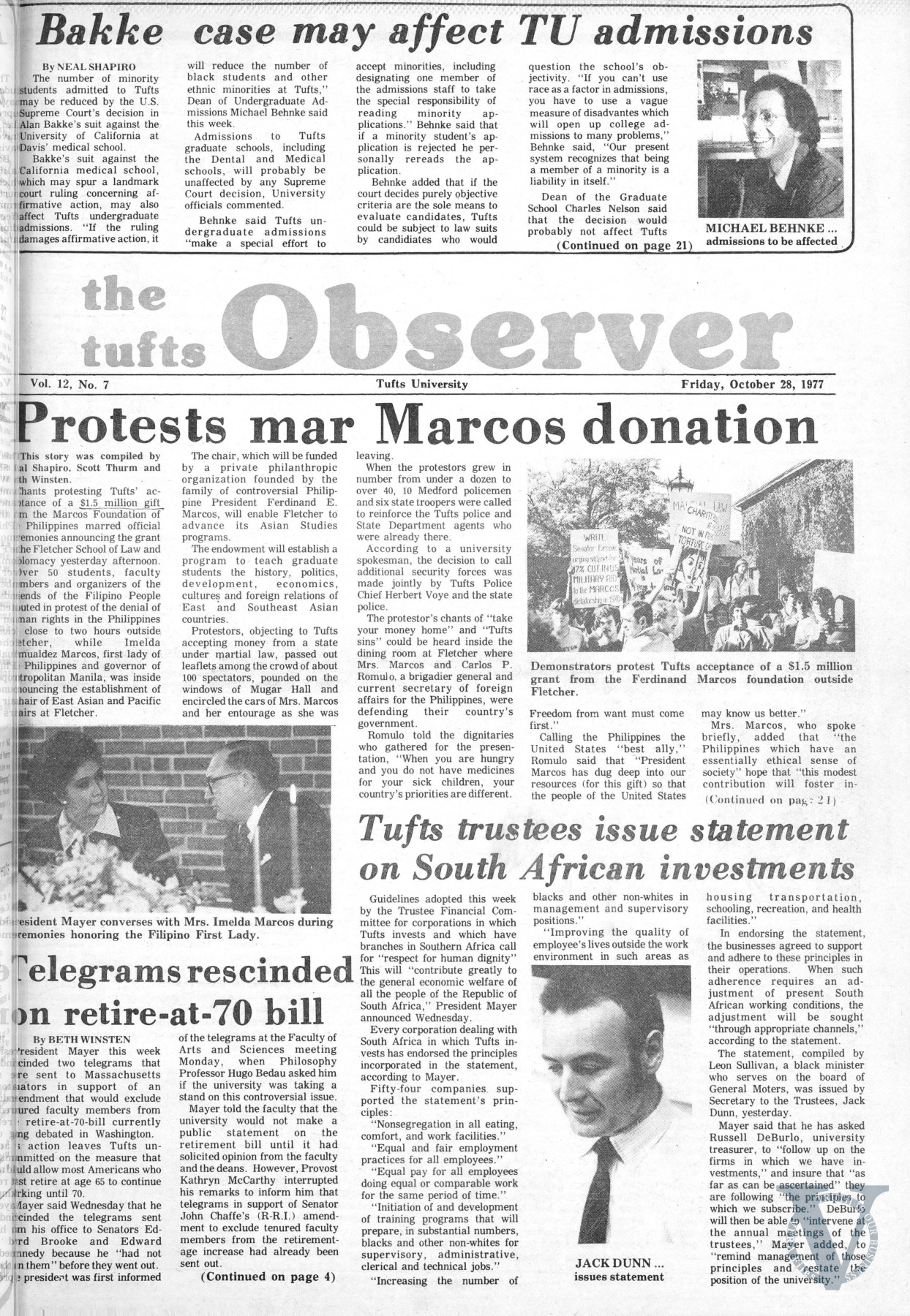

In an October 28, 1977 news report in the Tufts Observer, Tufts University’s student publication, Goonewardene broached the idea for the grant to Francisco Tatad, Marcos’s secretary of public information. The move was known to Edmund A. Gullion, dean of the Fletcher School.

Seven months later, on September 06, 1977, in a confidential cable from the United States Embassy in Manila to the Secretary of State in Washington, DC, it was mentioned that Gullion “departed Manila today after receiving a written commitment of the Marcos Foundation to provide an endowment of $1.5 million for the ‘The Ferdinand E. Marcos Chair of East Asian-Pacific Affairs’ at Fletcher.”

The Marcos Foundation

As he was about to start his second term as president and moved “by the strongest desire and the purest will to set the example of self-denial and self-sacrifice,” Marcos announced on December 31, 1969 that he had “decided to give away all my worldly possessions so that they may serve the greater needs of the greater number of our people.”

“I have therefore given away, by a general instrument of transfer, all my material possessions to the Filipino people through a foundation to be organized and to be known as the Ferdinand E. Marcos Foundation. It is my wish that these properties will be used in advancing the cause of education, science, technology and the arts,” Marcos said.

On January 21, 1970, formal papers of incorporation were filed before the Securities and Exchange Commission. In a Vera Files article, Miguel Paolo P. Reyes detailed the various uses that the Marcoses put their foundation into and how eventually the idea of dole outs from the Marcos Foundation “mutated into the scams that further propagated the myth of bounty for loyalty to the Marcoses.”

To go back to Gullion’s scheming with Marcos, according to the cable, on September 5, 1977, Gullion met with Marcos and Foreign Secretary Carlos P. Romulo. “Gullion opined that Marcos’ essential purpose in endowing the chair was to enhance his image in the U.S.,” it stated.

Gullion’s other concern was “how to handle the announcement of the endowment.” There were discussions that Romulo could do it when he attended the United Nations general assembly that October or Marcos himself in an official visit later that year.

The U.S. Embassy in Manila made a comment that they “did not encourage Gullion in his thinking about some sort of official visit by Marcos.”

It was Imelda, the other half of the conjugal dictatorship, who eventually went to the US. She headed the Philippine delegation to the UN general assembly and scheduled an event at Tufts University to announce the Ferdinand E. Marcos Chair of East Asian and Pacific Affairs endowment at Fletcher.

On October 26, 1977, a day before the announcement, the Boston Globe ran a report comparing the Marcos endowment with those that Harvard received in 1975, also $1 million from the Korean Traders Scholarship Association to put up a professorial chair in modern Korean economy and society. It was largely seen as a public relations effort to boost the image and encourage U.S. investments in South Korea, notwithstanding Park Chung-hee’s repressive regime.

The Boston Globe report foreshadowed Tufts’s justification for the Marcos endowment. “Harvard defended the $1 million Korean gift on the grounds that it was strictly for academic purposes and in no way ties Harvard to the controversial Korean government,” the article said.

Gullion was quoted as saying that “the money is from Philippine foundations and other organizations and not tied to the government . . . we shall be cooperating with the University of the Philippines in the studies. The endowment is from private funds, one of which is the Ferdinand Marcos Foundation, named after the president.”

The end part of the report noted Gullion’s “worldwide fundraising campaign . . . to support the school and its studies,” and “made several trips to the Philippines to discuss the grant with President Marcos and members of the foundations.”

There was, however, no other source for the endowment except the Marcos Foundation. But in the press accounts of the announcement, just like in the October 28, 1977 Associated Press (AP) report by Michael McPhee, “school officials and visiting dignitaries made several references that the money came from private sources and not from the Philippine government.”

The Protests

In the afternoon of October 27, 1977, as Imelda arrived at Tufts University under strict security measures, demonstrators hounded her on campus. AP reported that upon hearing the chant, “We don’t want your blood money,” university officials and members of Imelda’s entourage, including Romulo and Tatad, were “visibly annoyed.”

The Tufts Political Action Group and the Friends of the Filipino People led the protest that lasted throughout Imelda’s two-hour visit. Yet when news of Imelda’s visit appeared in the Marcos-controlled Daily Express on October 29, 1977, they were lumped together as “anti-Marcos elements . . . including many picket-for-hire-to-chant ready-made protest slogans.” The article was quick to add that there were no Filipinos among them and that Imelda’s visit lasted a full five hours.

Both details were lies.

Tufts University President Jean Mayer, said to be a personal friend of the Marcoses, hosted a luncheon for Imelda after a meeting with members of the faculty.

Protestors shouting “Who’s taking a beating while you’re in eating?” were heard by those taking part in the luncheon.

For Mayer, the Marcos endowment was a “sacrificial gift from a country struggling in its development.” He awarded Imelda a citation of distinction and said:

“By her determination, persistence, and ingenuity, Mrs. Marcos has succeeded in advancing the cause, not only of her people, but also the cause of the developing world in every corner of the globe. In partnership with her husband, Mrs. Marcos has been instrumental in establishing the Republic of the Philippines as a leader in the Third World and as an eloquent spokesman in the New Economic Order.”

“By her support of the artistic creativity, including revitalization of traditional and rural arts; her concern for ameliorating the problems of rapid urban development; her leadership of the Nutrition Foundation of the Philippines; and her support for UNICEF, Mrs. Marcos has demonstrated deep humane concern.”

“By her act of coming to Tufts University to inaugurate the Ferdinand E. Marcos Chair of East Asian and Pacific Affairs at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Mrs. Marcos has highlighted her interest in the continuation of the best possible relationships between government, business, and education, in the Philippines and the United States of America.”

During the luncheon ceremonies, the October 28, 1977 issue of the Tufts Observer reported that Imelda spoke briefly, expressing what she hoped the Marcos endowment could achieve. That it should “foster international understanding,” address the “poverty of accumulated literature on the Philippines,” which for her, were “largely one-sided and prejudiced.” Lastly, she hoped that the Marcos Chair would gain students who will espouse a “sensitivity to stand above bias and prejudice and appreciate the meaning of alternative existence.” A not so veiled way of saying that their effort should serve the Marcos autocracy.

As Imelda was whisked away in a white limousine from the campus to the airport (the Tufts Observer counted ten limousines for her entourage), Marian Christy of the Boston Globe, in an October 28, 1977 report, wrote that scores of demonstrators, “students and Filipino expatriates,” were shouting, “Marcos go home! Marcos go home!”

Another report from the Boston Globe estimated the number of demonstrators at about a hundred that included members of the faculty. The newspaper managed to get the reaction of Eugenio Lopez Jr., who had just settled in Boston after his daring escape from a Marcos prison with Sergio Osmeña III on October 1, 1977.

Lopez told the Boston Globe that he “cannot understand how a prestigious university like Tufts can award a plaque for humanitarianism when, in fact, she and her husband have done nothing but debase the humanity of the Filipinos.” He added that the endowment had been “expropriated by blackmail from the people and I would say that this is blackmail money that she has given Tufts University.”

Lopez’s criticism was echoed by the Tufts Observer’s editorial in its October 28, 1977 issue. “The grant, given yesterday by Imelda Marcos, wife of the dictator of the Philippines, comes from gifts of private citizens and corporations in the Philippines. It is these people who have profited from Marcos imposition of martial law on the island, from imprisonment of over 20,000 persons for political dissidence, from the suppression of political parties, and basic civil and constitutional rights. Justice is granted by military tribunals and freedoms of the press, speech, and assembly are virtually nonexistent.”

In soliciting and accepting the grant, “Tufts officially condones the actions of Marcos by not rejecting the grant. The object of the grant from the foundation’s point of view is to bolster the reputation of Marcos throughout the world. By taking the money, therefore, Tufts tacitly publicizes Marcos as a generous human being, a side of his personality he has rarely shown to his own citizens.”

On November 5, 1977, as Imelda returned to Manila, the Tufts board of trustees approved the terms of the Marcos grant. They consisted of an annual payment of $500,000 for three consecutive years from the inauguration of the grant and a one-time administrative fee of $75,000.

Saul A. Slapikoff of the Get Marcos Off Campus Committee and an associate professor of Tufts University, with 97 others, wrote to the Boston Globe on November 9, 1977 to denounce the acceptance of the Marcos grant. They argued that “the Ferdinand Marcos Foundation has the money to give to Tufts because the Marcos family and other wealthy Philippine families have enriched themselves by their dictatorial rule at the expense of the Philippine people.”

“We find it ironic,” Slapikoff’s group wrote, “that Tufts University, an institution purportedly committed to humane values, would accept money from the family of the Philippine dictator. This appears to be the worst sort of expediency and can only be a source of shame to the university.”

In Manila, Imelda, in her arrival statement said that she “found it opportune to be present at the formal inauguration of the Ferdinand E. Marcos Chair for East Asian and Pacific Studies at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.”

“Through this Chair, Tufts University hopes to make a more significant contribution to serious scholarship on Asia and the Pacific, and to raise the level of understanding of Asian affairs throughout the world, particularly in the United States. The Marcos Foundation has arranged to endow the Chair and support its program out of contributions from the private sector and its own.”

Imelda’s statement finally made clear that it was only the Marcos Foundation which was behind the endowment. What the Marcos Foundation can give, it can also take away—which it did.

The Fallout

The blowback from the acceptance of the Marcos Chair raged in the American press for some more months. The Tufts Observer kept track of the controversy. On December 2, 1977 it released a four-page “Marcos supplement” highlighting the university’s contrasting responses to the Marcos grant.

In the supplement, the Tufts Observer reported that “several members of the Board of Trustees indicated . . . that they voted to accept the $1.5 million grant from the Marcos Foundation without being fully or accurately informed about faculty opposition to the gift and about the political situation in the Philippines.”

Other members of the board, like its vice chairperson Warren Carley, denied this saying, “We didn’t spend a couple of weeks investigating the thing . . . I was told that there were understandable reasons for the so-called repressive activities. The Filipino government is under attack by guerillas, terrorists and communists who are trying to disrupt the government with violence . . . I don’t think as trustees we have to resolve the tribulations of another society.”

Gullion once again issued a defense on why the Fletcher School accepted the grant. He harked back to the Thomasites in the days of America’s colonial conquest of the Philippines and on how they “laid the foundations for higher secular education in the Philippine islands,” hence the grant from the Marcos Foundation should be seen “in gratitude and token repayment of a spiritual obligation.” He added that there were “no strings to this gift.”

Members of the faculty strongly disagreed with Gullion. Peter Dreier, an associate professor of sociology, asked: “If the Fletcher School appoints a scholar critical of the Marcos Regime, will installments two and three ever arrive? Isn’t this method of allocating the $1.5 million a subtle ‘string?’”

“Tufts University,” he continued, “by actively seeking out and then accepting the Marcos Foundation money has lent its name and prestige to a dictator trying to wash his bloody hands and bolster his image with philanthropy.” Dreier called on the leadership of Tufts University to “rescind the ‘citation for distinction’ [given to Imelda]. Return the Marcos Foundation money.”

The Tufts Observer Marcos supplement also reproduced in full the Daily Express report mentioned earlier. But instead of the original headline, “US school opens special FM Chair,” it became “Demonstrators called ‘pickets-for-hire’.”

Included was a copy of a letter that Sergio Osmeña III and Eugenio Lopez Jr. wrote to the dean of the Harvard Business School. In condemning the acceptance of the Marcos grant, they pointed to the “widely known fact that Mr. and Mrs. Marcos have enriched themselves while in public office through corruption and extortion. One can only conclude that what was given to Tufts on the pretext of philanthropy was in fact ‘blood money’ of the Filipino people.”

A month later, on January 20, 1978, the Tufts Observer gave an update on the controversy that by then had spilled over to the broader national U.S. media.

It reprinted the December 18, 1977 lead editorial of the New York Times criticizing Tufts. It read: “The proposed chair is to honor and bear the name of a man whose values no university should honor, certainly not with his money during his lifetime. What the university is here selling became instantly clear when Mrs. Marcos came to deliver the money and received a university citation honoring her for ‘deep [humane] concern’.”

On December 29, 1977, a column in the Washington Post by Hobart Rowen verged on the grotesque when it suggested that Tufts’s fawning attitude towards the conjugal dictators in contrast to the “oppression, poverty, and slums” in the Philippines, was “enough to make anyone who knows the Philippines . . . throw up.”

Responses from university officials and other scholars, for or against the Marcos grant, continued to eat up space in various publications all throughout 1978. Then the debate died. It seemed everybody but Marcos had just been had.

The Dissolution

On November 9, 1978 the AP broke the story that Marcos was “four months past due on paying a $500,000 installment” for the chair. AP quoted Harry Zane, Tufts director of public information, as saying that Marcos’s people “were unable to get the money together.” Hence, no money, no Ferdinand E. Marcos Chair of East Asian and Pacific Affairs.

A November 10, 1978 report in the Tufts Observer, citing information from Zane, stated that the “Marcos Foundation sent $75,000 in place of interest on the entire $1.5 million promised, bringing the total already paid to $150,000 . . . The foundation paid a similar $75,000 in 1977.”

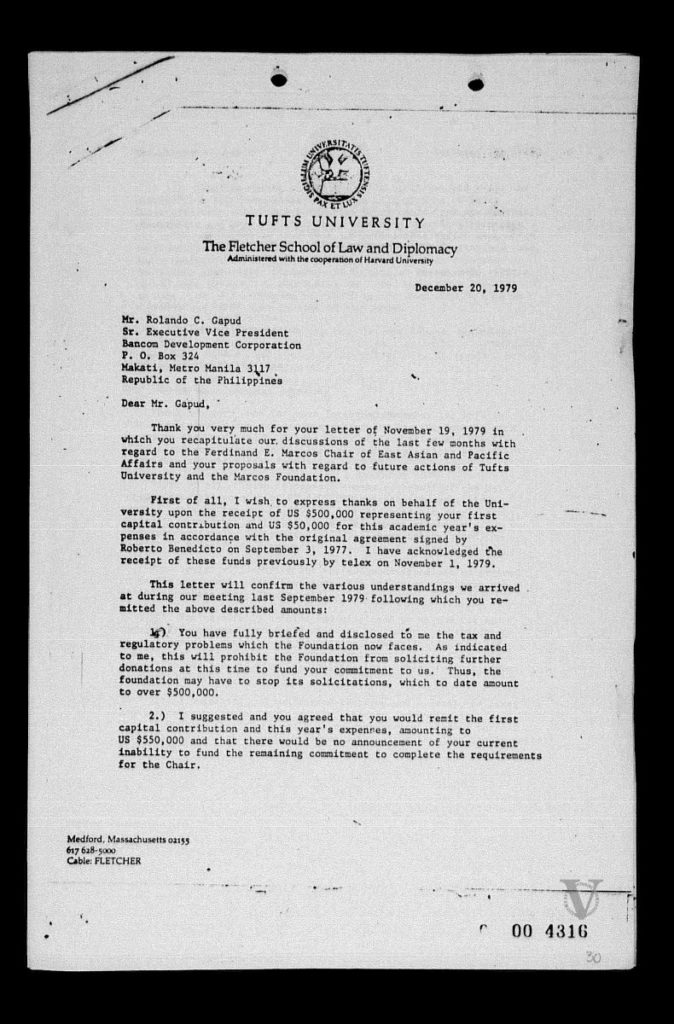

Unsigned copy of the December 20, 1979 letter to Mr. Rolando C. Gapud, senior executive vice president, Bancom Development Corporation from Jeffrey A. Sheehan, assistant dean, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Roll 171, images 141-42, PCGG Digitized Files.

A year later, on November 19, 1979, Rolando C. Gapud, senior executive vice president of Bancom Development Corporation and executive director of the Marcos Foundation, wrote to Jeffrey A. Sheehan, assistant dean at Fletcher School, that the Marcos Foundation would be unable to honor the full amount of the grant. The $500,000.00 due for the first year of the Marcos Chair plus $50,000.00 was all the Fletcher School would receive.

In Sheehan’s reply to Gapud on December 20, 1979, he enumerated the points that they had agreed on in their previous conversations.

First, the reason why the Marcos Foundation was reneging on its commitment:

“You have fully briefed and disclosed to me the tax and regulatory problems which the Foundation now faces. As indicated to me, this will prohibit the Foundation from soliciting further donations at this time to fund your commitment to us. Thus, the foundation may have to stop its solicitations, which to date amount to over $500,000.”

There was money enough to fund the second year of the Marcos Chair but the Fletcher School would not receive any of it.

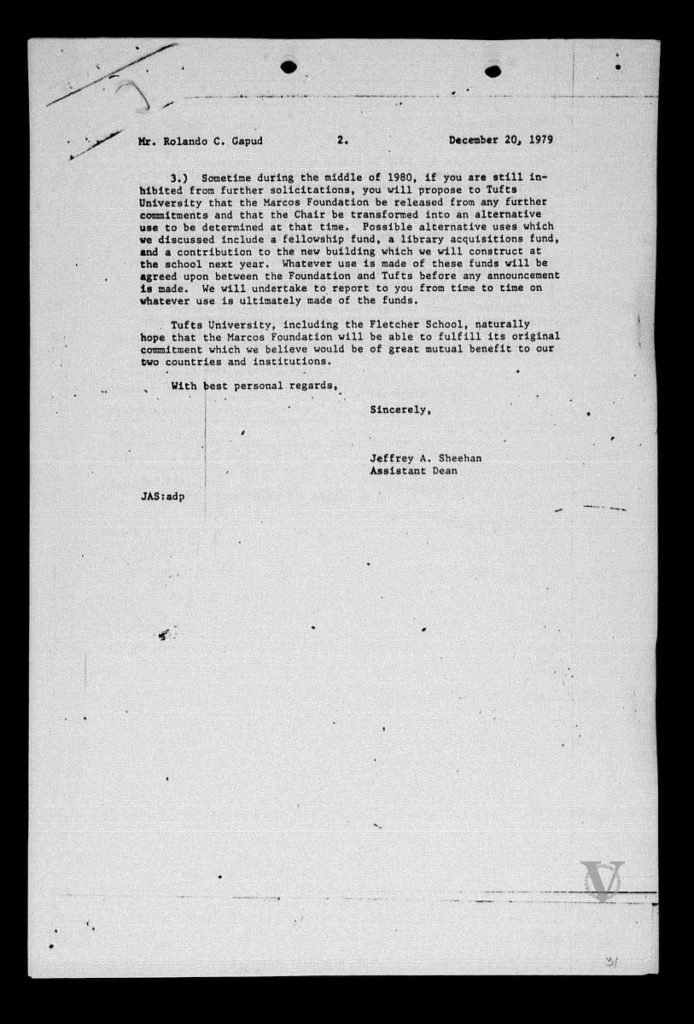

The second and third points were all about saving face as it was agreed that the endowment would be dissolved.

Sheehan agreed that “there would be no announcement of your current inability to fund the remaining commitment to complete the requirements for the Chair.” And if by “the middle of 1980, if you are still inhibited from further solicitations, you will propose to Tufts University that the Marcos Foundation be released from any further commitments and that the Chair be transformed into an alternative use to be determined at that time.”

Before this discussion towards dissolution between Sheehan and Gapud, a curious news article appeared in theTufts Observer with this headline: “Marcos grant paid; bonus for patience.”

“Philippine President Ferdinand E. Marcos personally delivered a check for $2.5 million to the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Tuesday afternoon, according to Assistant Fletcher Dean Jeff Sheehan. Sheehan said that Marcos entered his office disguised as a delivery boy from a bakery and nonchalantly withdrew the check from a seven-layer fudge ripple cake.”

It was Tufts Observer’s April Fools’ Day edition.

Finally, in January 1981, in an announcement well circulated in the U.S. media, Tufts University announced that there would be no academic chair in the Fletcher School named after Marcos since he failed to produce the $1 million necessary to complete the $1.5 million pledge to the university.

In a post-Edsa inventory of Malacañang by the Presidential Commission on Good Government, there is an item listed, M02-0176-1A1: Plaque for IRM [Imelda Romualdez Marcos] in a plastic frame from Tufts University.

At least Imelda got a plaque in a plastic frame. Ferdinand never got his chair.

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher of the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Miguel Paolo P. Reyes provided research assistance in writing this piece. Ariate, with Reyes and Larah Vinda Del Mundo are the authors of the book, Marcos Lies. Buy the book here.)