(First of three parts)

When ride-hailing platforms Grab and Angkas fail to match him with a ride so he can get to work on time, “Joseph” turns to an unlikely website: Facebook.

Last August, he joined a massive virtual community called Angkas Riders and Passengers Group (ARPG), which is exactly what it sounds like. There, commuters like him can post their “PU” and “DO”—shorthand for pickup and dropoff—along with a screenshot of the two locations mapped out on Google Maps, and then compute their own fare based on the group’s established fare guide.

Within seconds, bike owners would swarm Joseph’s inbox. He just has to respond to one—usually the one nearest to him, or familiar to him—and decline the other offers.

“It’s faster and more convenient,” he said. “Usually, too, I’m already in accessible areas like Intramuros (Manila), where riders tend to clump together.”

Bike owner Kevin Badique launched the immensely popular page in December 2017, a month after transport regulators shut down motorcycle-hailing app Angkas for operating bikes for hire. Displaced owners and passengers promptly populated the group, and within weeks established among themselves a transactional system governed by computer slang and nonbinding community guidelines.

The Inquirer spoke with some of ARPG’s administrators and riders, who all requested anonymity because of the legal intricacies surrounding habal-habal (bikes for hire).

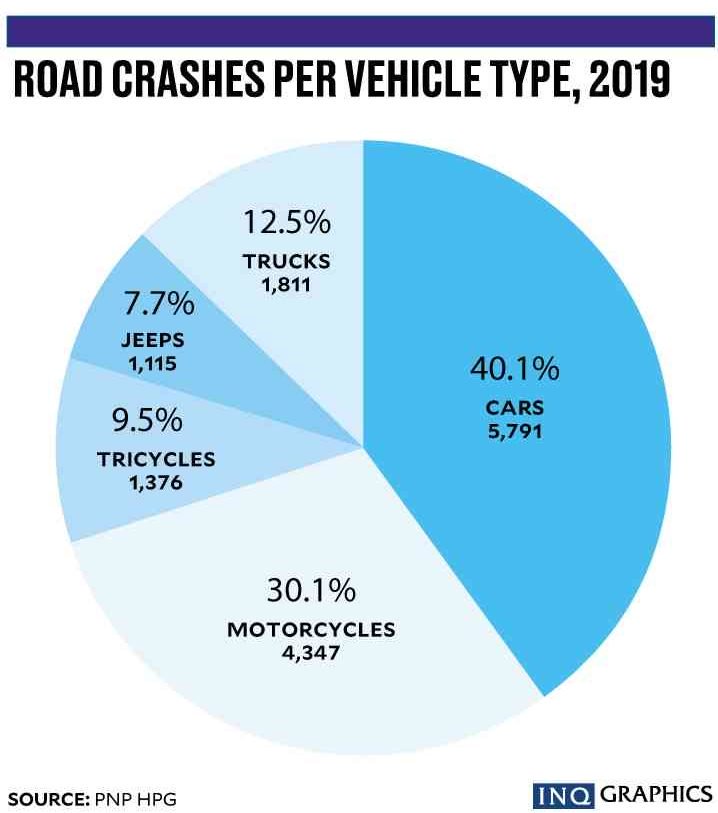

Motorcycles for hire, deemed unsafe by transport regulators, are banned under Republic Act No. 4136. Data from the Philippine National Police-Highway Patrol Group show that bike crashes comprised 44 percent of the more than 9,600 crashes recorded in January-September 2019 alone.

It’s why Angkas is undergoing a six-month pilot test to determine whether bikes, when subjected to strict regulation and professional standards, can be used for public transport.

Only bikes registered on Angkas are temporarily allowed to operate as taxis, according to the Department of Transportation (DOTr). But other bike owners have realized they could capitalize on the government’s temporary ceasefire on habal-habal by building their base on Facebook, where neither the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) nor the DOTr can hold them accountable unless they’re caught by enforcers on the road.

Underground

“They’re like an underground digital economy,” observed LTFRB Chair Martin Delgra. “They have no franchises to operate, they have no business permit, you don’t know where they come from.”

Most ARPG members belong to an underground network of bike owners from Greater Mega Manila. They’re a mix of hobbyists, professionals and Angkas/GrabFood bikers who look to the page for a part-time job.

“I joined because it’s a good source of additional income,” said “Alberto,” a Manila barangay councilor. “I can’t leave my day job because it’s a public service.”

Some joined the group after failing Angkas’ rigorous screening process. “They told me I hit the pylons (orange cones, during the obstacle course exam), but I honestly don’t know how I could have done that,” said “Joe,” who works in parcel delivery. “So I looked elsewhere.”

In short, ARPG’s lenient rules allow bike owners who would have otherwise failed the guidelines set by the technical working group of the government for Angkas’ six-month pilot test to service commuters.

“We do offer our riders some training,” said “Kyrie,” ARPG coadministrator, “just not as strict as Angkas’. [Our] training just tests basic riding skills, no backriders.”

In comparison, Angkas’ skills assessment tests how well a rider can navigate an obstacle course with a backrider. Testing this particular skill is paramount in determining whether motorcycles can be used for public transport, Delgra stressed.

“They have to be trained not only how to be drivers of a motorcycle, but also as drivers of a motorcycle taxi. They have to be conscious that they have passengers,” he said.

Only 14 rules govern ARPG. Most are about page decorum, and only two deal with passenger safety.

Because the group has no regulations, it didn’t keep official member or accident records at least until July, when it registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as Riders Pilipinas Inc., said “Kath,” the group’s coadministrator and vice president.

What if members get into a crash? “We will take care of them,” she said. “We have this practice called ‘pass the helmet,’ where riders from each chapter can all donate however much they’re willing.”

She recalled that, at one time, P1,700 was collected from members to pay for another who got into a minor crash. “It’s all about helping our own.”

Full-blown

Now with more than 500,000 members, ARPG has snowballed into a full-blown informal transport group thriving on the free-for-all platform Facebook. State officials cannot touch it—at least, not yet—which means all transactions made in the group are unregulated and unmonitored.

The moderators try to keep the page on a tight leash, and the rule is to block and mute unruly accounts. But such measures aren’t sufficient to ensure its passengers’ safety on the road.

“Those groups come to life because there is clearly a need as public transport is not enough,” said Toix Cerna, Komyut spokesperson. “It’s more of a symptom of the lack of service for commuters. And keeping our eyes shut on these issues, we also risk not protecting our commuters who were just out of options in the first place.”

ARPG has the biggest membership among the motorcycle-for-hire pages that appeared shortly after Angkas was shuttered by the LTFRB.

But charity does not determine public transport. The technical working group’s guidelines, aimed at ensuring passenger safety, require that both bike owners and passengers have government-standard insurance (P400,000 in cases of death; P250,000 for injuries), Delgra said.

Moreover, the LTFRB does not currently accept applications for new transport network companies (TNCs), he said, adding: “The only one that we recognize is the pilot implementation being managed by Angkas. We are not yet entertaining any TNC application. We are waiting to complete the test so that we would have data to assist Congress on the several bills on motorcycle taxis.”

Regardless, ARPG seems unfazed by the fact that it is operating illegally.

“I mean, what else can you do when the riders are already here?” Kyrie said. “It’s better to have them under one umbrella where we can moderate them than for them to go off on their own. That’s more dangerous.”

Vulnerable

But the group’s lack of standards leads to mixed results on the road. For some, like Joseph, it can mean accidentally choosing an owner with a karag-karag (decrepit) motorcycle and a broken, smelly helmet.

But for women like “Nikka,” the lack of privacy of booking through their public Facebook account makes them especially vulnerable to sexual predators.

On Aug. 23, an owner with the Facebook name Enrique Sage Tan offered to take up her booking for a ride to her office in Taguig City. “But even though he said he was near me already, it took him a long time to get back to me, and I was already at the [pickup point]. Then he videocalled me.”

She answered, thinking he wanted to see where she was. To her horror, she saw him in the bathroom, masturbating.

Nikka posted the entire exchange on the group, asking the moderators for action lest she report the page. Instead, she was attacked viciously by other bike owners for persecuting all of them over the actions of a rogue member. The administrators never got back to her, she said.

Both Kath and Kyrie claimed they were very strict about such violations. “We’re currently undergoing a cleansing period [on the page]. We’re weeding out multiple accounts, posers, so we can distinguish which ones are legit riders,” Kath said.

But these can easily be bypassed by making another dummy account, Nikka argued.

“I think they really don’t know, or care, because there are just too many members. They’re not organized. So I felt it was a lost cause,” she lamented. “It’s not really clear whether it’s a business because it’s just a group.”

But ARPG appears poised to transition to exactly that: a business just like Angkas. It’s not the only one. And with competition moving in too early and unchecked by the government, the results of the pilot test—and efforts to legalize motorcycle taxis—may be compromised.

(To be continued)

This report, which was first published on the Inquirer, was produced under the Road Safety Journalism Fellowship carried out by Vera Files and the World Health Organization under the Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety.