In the forests of Palawan, there are trees older than memory.

Referred to as the Philippines ‘last ecological frontier, the province is home to over 105 of the 475 threatened species in the country, 42 of which are found nowhere else but here. It is a UNESCO-designated Man and Biosphere Reserve where the Palawan pangolin, the Philippine cockatoo, and the gentle dugong fight extinction alongside mangroves, old-growth forests, and coral gardens.

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, this single province holds ecosystems so diverse they stretch across sea, stone, and sky.

Its mountains hold stories and myths passed down through generations of Palaw’an, Tagbanua, and Batak. These indigenous communities, long the quiet vanguards of Palawan, believe land is not owned but served — not claimed, but kept.

But the mountains are being gutted.

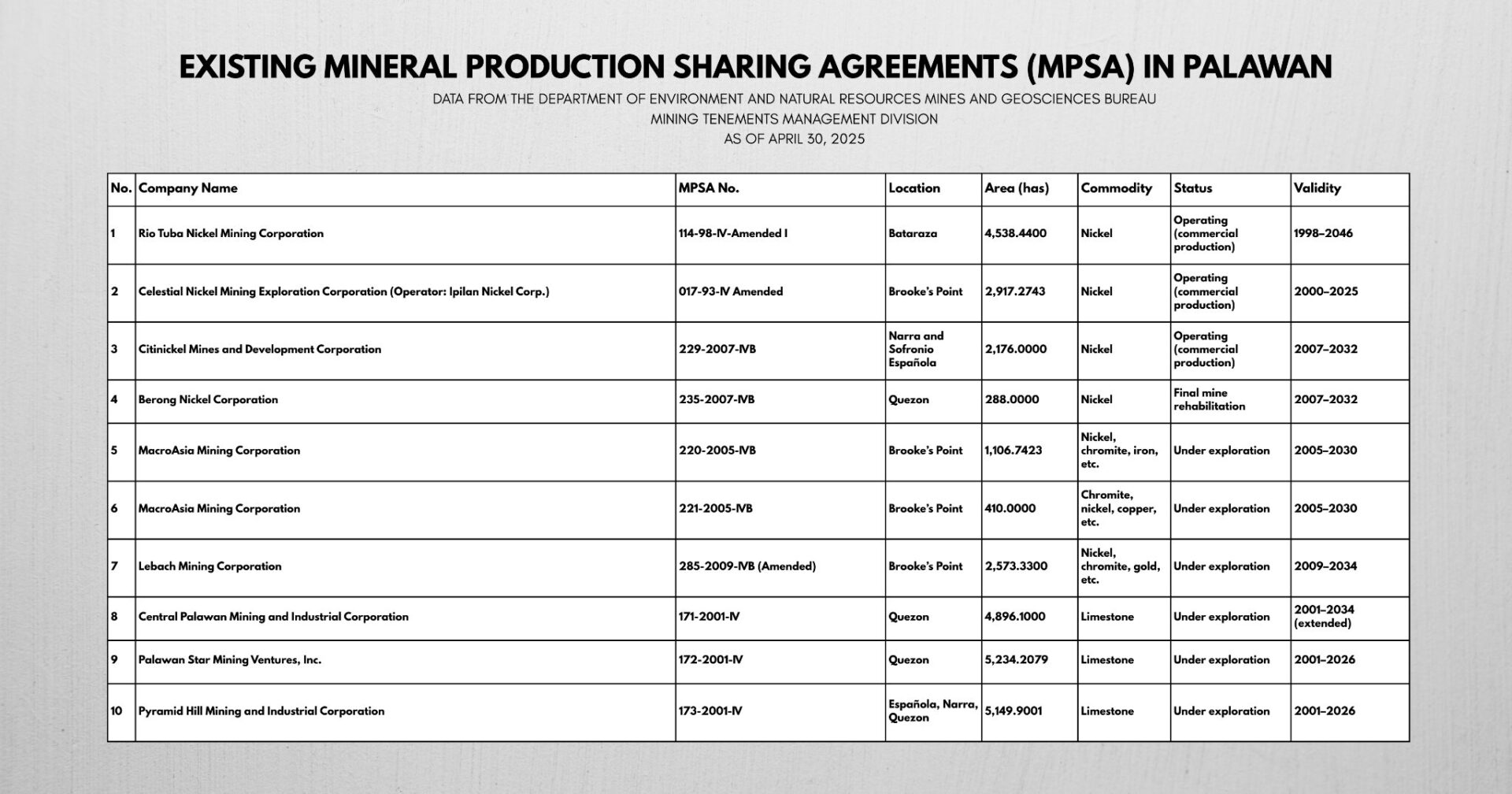

Since the 1990s, the Environmental Legal Assistance Center (ELAC) has tracked mining’s spread across Palawan. Today, according to them, more than 200,000 hectares bear its claims. A contract in waiting and a quiet erasure of what the land once fed, held, and meant.

Nickel, the metal primarily buried under ancestral domains of the province, has become a currency of power. The promise of wealth, jobs, and development has become a justification for intrusion. And resistance, in many places, has a price.

ELAC’s Executive Director Atty. Grizelda Mayo-Anda described the struggle as “a long and weary fight,” warning that it is worsening.

“Kasi habang tinatanong ninyo ko ngayon, patuloy pa rin ang pamumutol ng libu-libong punong kahoy sa Bulanjao Range. Nasaklaw iyon ng Bataraza at Rizal. Tuloy-tuloy pa rin ang reklamo ng mga magsasaka at ng mga katutubo na hindi nila magamit ang mga lugar [na sakop ng kanilang lupaing ninuno] at iyong mga magsasaka na natamaan ng baha at iyong lupain nila ay natakpan ng nickel laterite ay hindi pa rin nila magamit yung lupa nila,” Anda stressed.

[While you are asking me now, thousands of trees are still being cut down in the Bulanjao Range, which spans Bataraza and Rizal. Farmers and Indigenous communities continue to complain that they cannot use the areas within their ancestral lands. Farmers affected by floods, whose land has been covered by nickel laterite, still cannot use their land]

Three mining corporations currently operate in southern Palawan. Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corp. (RTNMC), Citinickel Mines and Development Corp. and Celestial Nickel Mining Exploration Corp. being operated by Ipilan Nickel Corp. (INC), primarily targeting nickel deposits. Their reach spans the towns of Brooke’s Point, Narra, Bataraza, and Sofronio Española, where forests once stood, and watersheds now bleed red.

In the battle between mining interests and indigenous peoples over ancestral lands, the fight has moved beyond the forests and into the heart of the democratic process.

Civil society groups and election watchdogs have observed that corporate greed has seeped into the electoral system, manipulating local politics to secure favorable outcomes for mining operations.

Local indigenous leaders have documented a pattern of campaign interference ranging from financial backing of pro-mining candidates to harassment and intimidation of anti-mining advocates.

The invisible hand

In the southern town of Brooke’s Point, former village council member and indigenous leader Nelson Sumbra experienced firsthand how mining companies meddle in local elections.

“Iyong time na kagawad pa ko, mayroon kasi unang una iyong pagbibigay nila ng kapital dun sa mga tumatakbo… ang tao boboto kahit hindi nila gusto dahil doon sa mga binibiga. (Back when I was still a village councilor, the first thing I noticed was how they provided capital to those running for office… People would vote even if they didn’t like the candidate because of what was being given to them)” he shared.

“Kadalasan nasa talo pa rin yung anti-mining kasi wala siyang pera,(Most of the time, the anti-mining candidate still loses because they don’t have money.)” he added.

Candidates backed by mining companies, he said, host events with giveaways and cash incentives that anti-mining advocates simply cannot match.

In the 2022 elections, a local source, who asked not to be named out of fear for personal safety, recalled how cash handouts were likened to COVID vaccines.

“May first dose, second dose, at ‘yung booster. Pero pera po ‘yung pinag-uusapan doon,(There was a first dose, a second dose, and even a booster. But what they were really handing out was money,)” he told Palawan News.

This is more than a metaphor. Residents said the final “booster”, or the largest payment, was given the night before the election.

“Sigurado ako na may palihim po silang binibigay. Ngayon nga po may bali-balitang straight vote daw po lahat ng empleyado nila sa minahan para suportahan ‘yung mga kandidatura ngayong eleksyon (I’m certain they’re secretly giving something. In fact, there are rumors now that all their mining employees are being made to vote straight for the candidates they’re supporting in this election)” the source said prior to the May polls.

For years, indigenous residents in Brooke’s Point have resisted mining operations that threaten their lands and watersheds. Yet, Sumbra said electoral interference has weakened their collective stand. “Yung iba napipilitan na lang kasi kailangan nila ng tulong, lalo na kapag eleksyon,” he said.

Local watchdogs and environmental groups have raised similar concerns, warning that mining influence during elections undermines both democracy and Indigenous rights.

Vote-buying in broad daylight

Former Brooke’s Point town Mayor and current Vice Mayor Mary Jean Feliciano was one of the few officials to aggressively push back against mining interests.

In 2018, Ipilan Nickel Corporation (INC), a mining company operating under Global Ferronickel Holdings Inc. (FNI) filed administrative cases for grave abuse of authority and oppression against her after she suspended its operations and demolished structures over illegal tree cutting involving more than 7,000 trees covering 20 hectares of old-growth forest . For that, she was removed from office, criminally charged, and harassed.

“Ay alam na ‘yan ng public. Noong nakaraan, ako ‘yung mayor, ang dami nilang kinaso—mga robbery, abuse of authority, disbarment. More or less isang dosenang kaso ang naisampa sa akin,” she recounted.

[The public already knows about that. Back then, when I was the mayor, they filed so many cases against me—robbery, abuse of authority, disbarment. More or less, a dozen cases were filed against me.]

“Oo, nakaranas ako ng intimidation… pananakot or threat. ‘Yung paglagay nila ng cross galing sa sementeryo sa bahay namin at sa opisina ko. Pero hindi ko alam kung kanino galing ‘yon… pero wala naman akong ibang kalaban eh kundi minahan,” she added.

[Yes, I experienced intimidation… harassment or threats. They placed a cross from the cemetery at my house and at my office. I don’t know who did it… but I have no other enemies than the mining company]

The Office of the Ombudsman overturned the charges in 2023, ruling that Feliciano acted within her official duties.

Feliciano echoed that mining companies are funding candidates to run for elections

“Meron silang pinapatakbong politiko na sinusuportahan nila financially. Meron akong kakilala na talagang inamin niya… noong nakaraang election, binigyan sila ng 1.3 million bawat isa ng minahan,” she said.

[They have a candidate they’re backing financially. I know someone who openly admitted that during the last election, the mining company gave each of them ₱1.3 million.]

Voters, she said, especially members of indigenous communities were listed and offered P5,000 in exchange for voting for mining-backed candidates and skipping her campaign events.

She said some men even blocked roads during a campaign rally in Barangay Salogon to stop residents from attending.

“Sinasabi na… nilista namin kayo, bibigyan namin kayo ng five thousand. Pero ‘pag nakita namin kayong umattend doon sa meeting nina Vice Feliciano… tatanggalin namin kayo sa listahan,” she relayed.

[They were saying… “We’ve listed your names, and we’ll give you five thousand pesos. But if we see you attending Vice Feliciano’s meeting… we’ll remove you from the list.]

“Yung five thousand pesos na pangako ay napakalaki noon para sa isang mahirap,” she added.

[The promised five thousand pesos is a huge amount for someone who is poor]

A price on culture: Indigenous division and displacement

The collateral damage is not only environmental. It is cultural. And sometimes, economic and personal.

“Una po, nahati po kami sa dalawa, pro-mining at anti-mining… Nag-aaway-away na po kami kahit mag-kakamag-anak… kanya-kanya na po, ” said Nolsita Siyang, a Palaw’an Indigenous leader in Brooke’s Point.

[First, we were divided into two groups. Pro-mining and anti-mining… There was fighting even among relatives… everyone went their separate ways.]

For Norima Tablon, nature has provided sustenance and livelihood for their tribe. But things had drastically changed when mining companies struck the first rock.

“Kasi dati naman po, noong wala pang pagmimina at wala pa pong full operation, nabubuhay po kami sa pagkaing dagat. Sa karagatan, halos bihira po kaming gumastos kasi marami pong shells na nakukuha, pati po sa isda, nangunguha kami. Halos libre nga po ‘yun, nakakapagbenta pa nga po kami, ” she recalled.

[Back then, before the mining operations began, we relied on seafood from the ocean. We rarely had to spend money because there were so many shells we could gather, and we also caught fish. It was almost free. We even earned from it.]

“Sa ngayon po, parang ang hirap na po namin makakuha, gamitin para sa sarili o ibenta bilang hanapbuhay. Maging sa amin pong sarili, hindi na po namin alam kung ligtas pa ang kinakain namin—lalo na po para sa aming pamilya. Ganoon din po sa inuming tubig,” she added.

[But now, it’s become very difficult to collect, to consume, or to sell as a livelihood. Even for our own consumption, we can’t be sure anymore if what we’re eating is still safe, especially for our families. The same goes for our drinking water.]

The area in contention is Mt. Mantalingahan, a 120,457-hectare protected landscape known to be the ‘mountain of the gods’ and Palawan’s highest peak. Conservation International considers Mt. Mantalingahan to be a critical biodiversity hotspot, harboring at least 861 plant species, including eight potentially undescribed species and 12 newly recorded in the Philippines. Its fauna includes 35 mammal species, 90 bird species, 30 reptiles, and 14 amphibians, with 23 species classified as globally threatened.

The landscape also serves as the headwater for 33 watersheds, providing essential ecosystem services like water supply, soil conservation, and carbon sequestration to local communities.

This sacred space to local communities, used for gathering medicinal herbs, holding rituals like Ulit, a shamanic healing ritual, and accessing clean water, have been fenced off, literally and figuratively by INC.

In 2023, the Supreme Court issued a Writ of Kalikasan against these mining companies and other government agencies for causing “serious and irreversible” damages within Mt Mantalingahan and its communities.

But the mining operations continued as the high court refused to issue a Temporary Environmental Protection Order (TEPO). Instead, INC was just required to “provide evidence to dispel concerns regarding potential harmful impact of a project to the environment.”

‘Hijacking’ the Democracy

Third party observers found the 2025 Elections as unprecedented. Mining companies are no longer content with trucks and permits. They want ballots. They want seats.

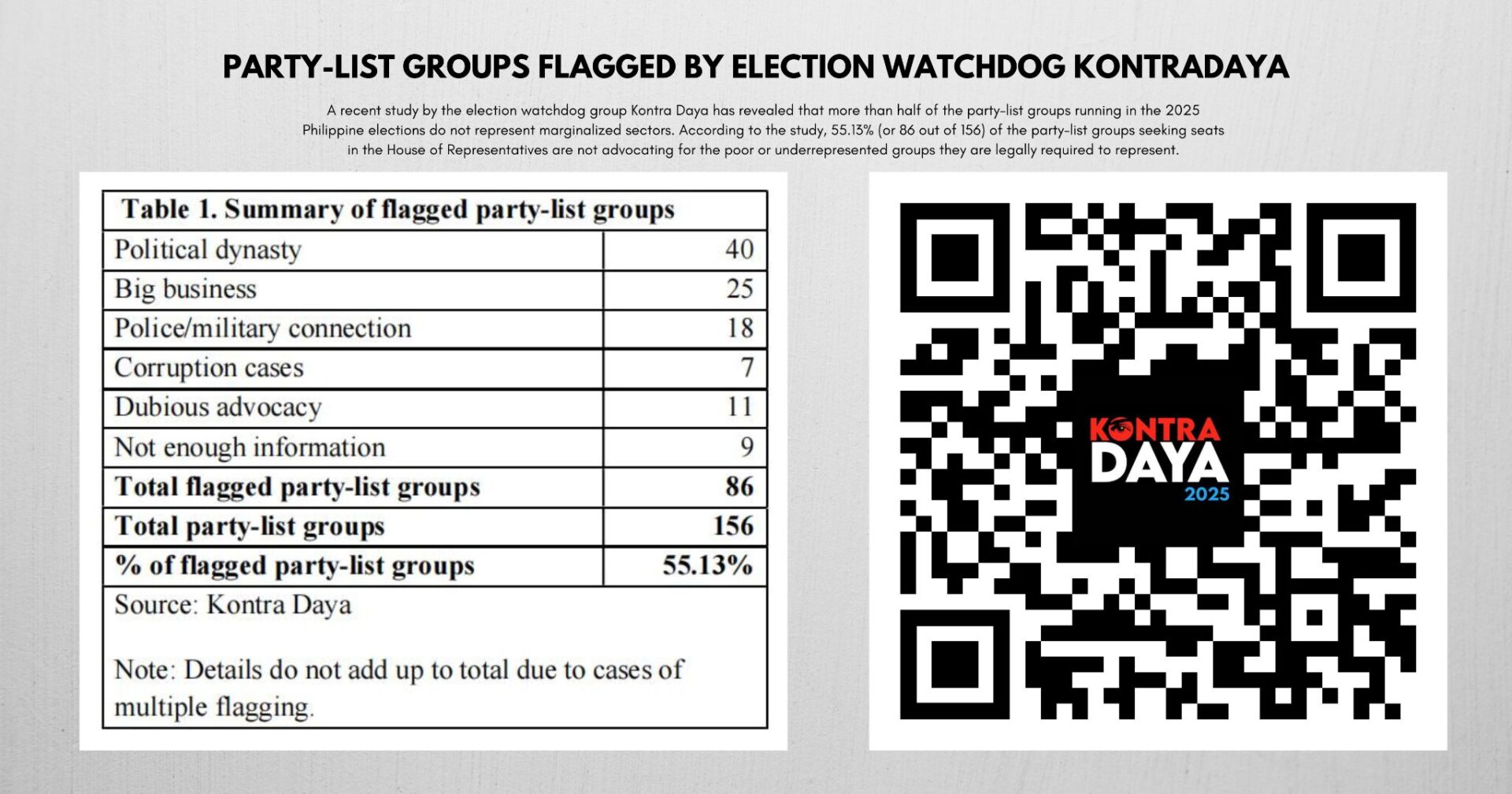

According to watchdog Kontra Daya, 86 of the 156 party-list groups that joined the 2025 elections have questionable ties to big business, political dynasties, and military interests. These include party-list groups that openly advance the mining sector’s agenda, as well as those that present themselves as champions of other sectors while covertly benefiting from mining.

Based on Kontra Daya’s 2025 partylist watchlist, the BBM Partylist, short for Bangon Bagong Minero (Arise New Miners) is effectively a mining consortium in legislative clothing. Its nominees include Carlo Antonio Co, Vice President of Kafugan Mining Inc. and a board director of the Philippine Nickel Industry Association; Ryan Rene Jornada, a top executive at Nickel Asia Corporation;Tonee Charmaine Hang, EVP of Kafugan Mining Inc.; and her husband, nominee Rodric Hang.

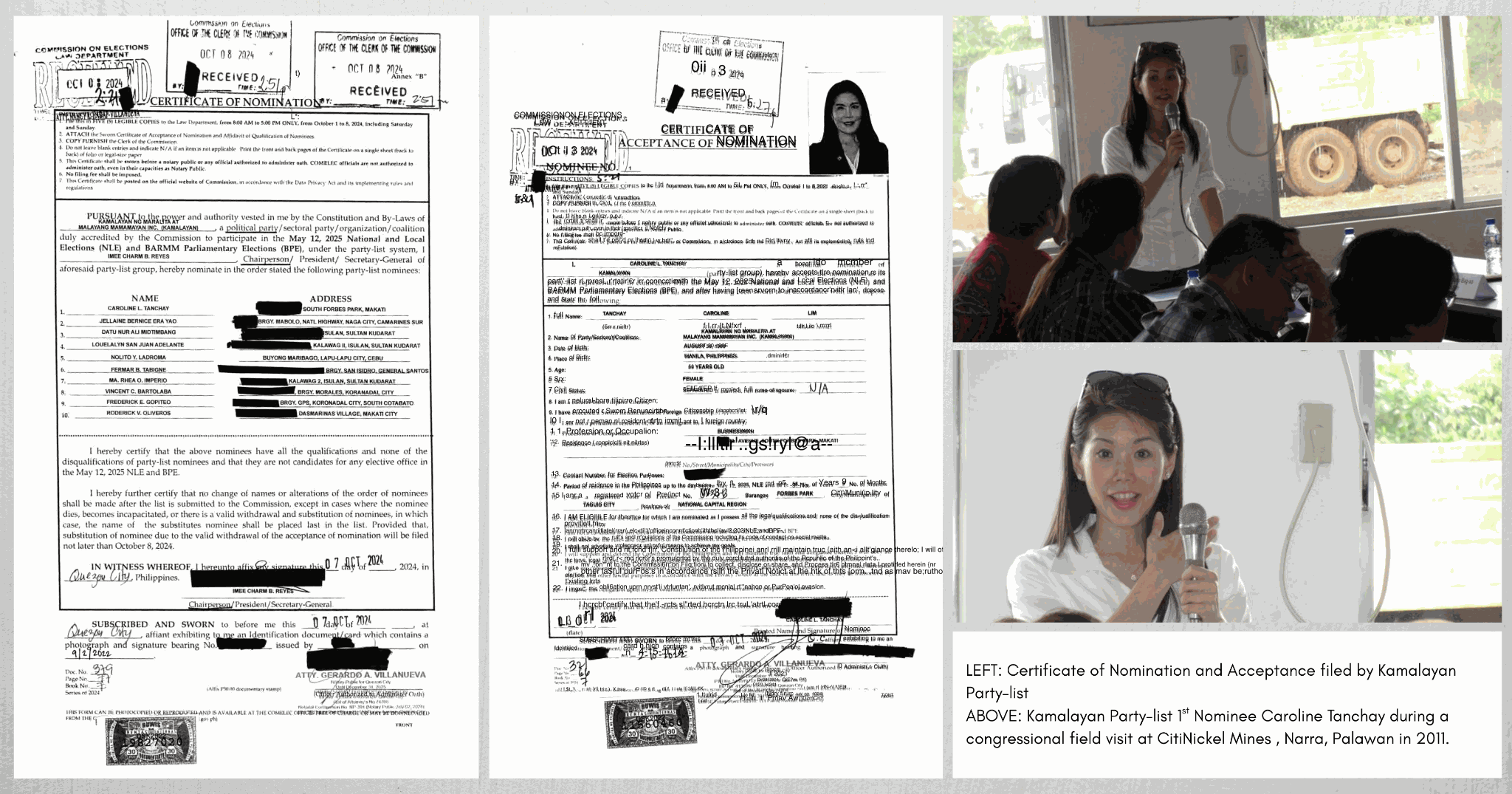

Meanwhile, based on their Certificate of Nomination and Acceptance (CONA) Kamalayan (Awareness) Partylist is headed by Caroline Tanchay former partylist representative of SAGIP Partylist and chair of Citinickel Mines and Development Corp., which operates in Narra, Palawan and has been repeatedly flagged for environmental violations.

According to a 2016 audit by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Citinickel violated numerous environmental laws. It failed to submit production reports, operate without a Strategic Environmental Plan clearance, and did not implement its Social Development and Management Program. Worse, its mining activities damaged a watershed — yet the firm remains operational.

These violations, by law, warranted suspension of operations under RA 7942 or the Philippine Mining Act and DENR Administrative Order 2010-21 but no shutdown came.

Indigenous Tagbanua communities in Narra, have also slammed the non-release of about ₱100 million in royalty shares from Citinickel’s operations in Barangay San Isidro, funds intended for development projects.

On April 25, the Commission on Elections issued a Show Cause order to Kamalayan Partylist for allegations of vote buying.

Tagbanua Leader Silvestra Dadison from Brgy. Princess Urduja, one of the impact sites of CitiNickel Development Corp in the southern Palawan town of Narra, saw how the partylist tried to sway votes in their area.

“Nung nakaraan grabeng pamigay nila ng mga damit, pero sabi ko sa kanila, kapag tiningnan natin yung damit na yan, damit lang yan, pero yung kapalit niyan, kapag yan yung binoto ninyo dahil sa kasikatan ng bigay bigay, kapag nandun na yan sa kongreso, isa sila sa mga mag aapruba ng mina,” she said.

[They were handing out a lot of clothes recently, but I told them, if we look at those clothes, they are just clothes. The real cost is that if you vote for them because of the popularity of these handouts, once they are in Congress, they will be among those approving the mines.]

“Kaya sila umuupo dyan kasi mina ang hawak nila. So kapag nakaupo na sila, talagang wala na tayong magagawa, wala na tayong kakampi,,” she added.

[That’s why they wanted the position because of their mining interests. Once they get in, there’s really nothing we can do, we have no ally left.]

Kamalayan in, BBM out, but…

After the May 2025 polls, Kamalayan’s 379,208 votes reached the threshold. BBM’s 110,994 votes fell behind.

The numbers, however, tell a larger story.

Kamalayan declared no sources of funds in its Statement of Contributions and Expenditures (SOCE). It reported ₱3,927,981.27 in spending. Of this, ₱2.425 million went to media advertisements. Another ₱1.192 million was listed for stationery, printing, and distribution of campaign materials.

BBM declared ₱2,479,236.18 in cash and ₱45,525,246.03 in in-kind contributions. The records show ₱45,403,904.60 spent on media advertising. Among the endorsers was television host Toni Gonzaga, who appeared in campaign plugs and produced a vlog narrating the benefits of mining.

The Commission on Elections rules define the campaign as a contest for congressional representation with only a maximum of P5.00 to spend per voter.

The spending records show another layer. Tens of millions were poured into advertisements that presented mining as industry, employment, and development. The audience’s reach went beyond the votes earned.

Measured by pesos spent, the outcome, for some on the ballot, was defeat. The outcome in public messaging was exposure.

Legal loopholes in the partylist system

The growing presence of these mining-affiliated partylists in the partylist elections has legal experts raising the alarm.

Professor Danilo Arao, Convenor of KontraDaya explained the root of the problem.

“Sa paglipas ng panahon… nagsimula na ang ‘hijacking’ o ‘bastardization’ ng partylist system. Ginagamit ito ng mga mayayaman at makapangyarihan para madagdagan ang kanilang upuan sa Kongreso, ” he said.

[Over time, the party-list system began to be hijacked or bastardized. The wealthy and powerful started using it to increase their seats in Congress.]

While the Partylist System Act of 1995 and the Bayan Muna vs. COMELEC Supreme Court decision emphasized that only those truly representing marginalized sectors should run, the 2013 Atong Paglaum case changed that.

“Kahit na sino puwedeng pumasok sa partylist system, kahit hindi ka galing sa sektor na sinasabi mong pinaglalaban mo,” Arao said.

[Anyone can enter the party-list system, even if you don’t actually come from the sector you claim to represent.]

As a result, according to KontraDaya, billion-peso corporations are now represented in a political space meant for fisherfolk, farmers, workers, and indigenous peoples.

Although this year’s number is lower than the 70 percent flagged in 2022, Arao noted that 40 groups in this year’s elections still have links to political families, slightly down from 43 in the previous polls.

Atty. Ryan Jay Roset of the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (LENTE) calls this trend a “departure from the spirit of the Constitution.”

He warns that mining-backed partylists could pose severe conflict-of-interest concerns.

“The mining sector is a regulated industry… kapag ang nominee ay galing sa isang mining outfit (so when a nominee comes from a mining company), that may give rise to conflict of interest issues,” Roset said.

Environmental policy at risk

With mining-backed partylists securing seats, ELAC warned that pro-mining groups could use their position in Congress to advance policies and decisions that favor their interests. This may include key legislation including efforts to lift mining moratoriums, approve large-scale projects in environmentally critical areas, and weaken regulatory oversight.

The overlapping interests of mining corporations and political aspirants, especially through partylist infiltration, raise serious concerns about genuine representation, particularly of farmers and Indigenous communities.

Mayo-Anda warns that such legislative influence could derail years of environmental protection work in Palawan.

“So makikita mo na meron silang ganyang effort para dumami pa yung kakampi nila sa Kongreso, [So you can see that they’re making a deliberate effort to increase the number of their allies in Congress.]” she said. “Kahit tayo, mahihirapan na tayo sa Kongreso kung ultimo partylist ay nandyan din yung kinatawan ng mga minahan. [Even we will struggle in Congress if even the party-list seats are occupied by representatives of mining companies.]”

In the past, efforts to rein in mining and overhaul land-use governance have repeatedly stalled. The National Land Use Act, Sustainable Forest Management Act, and Alternative Minerals Management Act all cleared the House but remained blocked in the Senate. Similarly, a much-anticipated fiscal reform proposing an ore export ban failed to survive the bicameral process with lawmakers ultimately dropping the provision.

Anda emphasized that although a moratorium on new mining applications is currently in place, active operations remain unchecked. If Congress becomes populated with pro-mining allies, such ordinances could be weakened or repealed.

After the Vote: Palawan’s uncertain future

In 2010, Palawan was promised a reprieve. Then-President Benigno Aquino III, under pressure from the outcry that followed Dr. Gerry Ortega’s assassination, declared a moratorium on new mining applications. It was supposed to be the line in the sand, the government’s answer to decades of open pits and poisoned rivers. The moratorium was meant to still the drills and silence the backhoes.

It did not.

The policy froze permits, but not the mines. Companies already granted exploration rights kept digging. The trucks kept running down red dirt roads, their wheels slick with laterite. On rainy days, the run-off turned rivers orange, children wading through water that burned their skin.

Year after year, the promise frayed.

Until 2017, President Rodrigo Duterte threatened to ban open-pit mining. Gina Lopez, Doc Gerry’s longtime ally and then environment secretary, ordered mines closed. But the companies that carved from rock and profit won. Lopez was removed. The pits stayed open.

As the country staggered through the pandemic in 2021, Duterte’s government lifted the moratorium. Mining companies celebrated. Palawan’s mountains grew shorter.

In 2024, the call rose again. What began as a push for a 25-year ban grew louder in hearings, doubled in February, and by March 2025 became law: a 50-year moratorium on large-scale mining. For half a century, the island would be protected. At least, on paper.

Then the elections came.

Governor Dennis Socrates, who had defended the ban, lost. His replacement is San Vicente Mayor Amy Alvarez, the first woman governor of the province and by law, will chair the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development. The office is mandated to protect Palawan from extractive industries through a special law, Republic Act 7611 or the Strategic Environmental Plan for Palawan or SEP Law.

This continues to raise doubts. Some call her pro-mining. She insists otherwise.

“San Vicente is the first TIEZA tourism enterprise zone of the Philippines and being its mayor I fully support this moratorium,” Alvarez told lawmakers in February.

She spoke of balance, of collaboration, of preservation beside progress. Conservation groups welcomed her. But they are still waiting for action.

“Even the governor herself. She was the president of the league of the municipalities in Palawan, she was there and she said there was no problem [with the moratorium],” said ELAC’s Atty. Mayo-Anda.

“Because that is an ordinance, our expectation and hope is that the ordinance will be implemented because they are mandated to do that,” she added.

Outside the halls of government, the companies are moving.

“As of June 30, there are mining companies continuously going to the communities, getting consent,” Mayo-Anda said, naming Redmont in Narra and Rizal, Berong Nickel in Quezon.

In Narra, the local council said yes despite the moratorium. It endorsed Redmont’s application for an exploration permit in Barangay Calategas.

Vice Mayor Edmond Gastanes presided over the vote. He said the application had been filed in 2006, renewed in 2011, and only needed resubmission. He admitted the endorsement clashed with the moratorium but pointed to lawyers who called the provincial ban unenforceable.

“Sabi ng abogado walang legal effect sapagkat it violates the Mining Act,” Gastanes said.

[The lawyer said it has no legal effect because it violates the Mining Act]

He cited the Supreme Court’s May 2025 ruling that struck down Occidental Mindoro’s 25-year mining ban. The justices ruled that provinces cannot impose blanket prohibitions. The Mining Act of 1995, they said, belongs to Congress, not councils.

“Mate-test natin ngayon ang ngipin ng ordinance na ito,” said Board Member Rafael Ortega Jr., vice chair of the provincial board’s environment committee.

[We will now test the strength of this ordinance.]

The ordinance exists. The Mining Moratorium Council, created to enforce it, has yet to meet. Mayo-Anda calls the delay dangerous.

“It’s basically to convene the Mining Moratorium Council,” she said. “So magkaroon ng implementing guidelines kasi wala pang guidelines at naabutan na nito.“

[So that there will be implementing guidelines, because there are none yet and this one was caught over without it.]

On the ground, the resistance continues. Tagbanua leader Silvestra Dadison asked her councilors to remember what is at stake.

“Dapat pag isipan nila yung pinag-aaprubahan nila na mina, kasi hindi lahat ng proyekto maganda (They should think carefully about the mines they are approving, because not all projects are beneficial),” she said. Narra, she reminded them, is Palawan’s rice granary. “Kapag dito po isinulong niyo ang mining hindi na yan rice granary, mining granary na po yan. (If you push for mining here, it will no longer be a rice granary, it will become a mining granary.)”

She stood that they have not lost hope.

“Kung may mina man, titingnan po nila. Nararapat ba dito sa lugar na ito? Pero kung hindi, sana wag na po aprubahan,” Dadision wished.

[If there is a mine, they should look at it. Is it appropriate for this area? But if not, hopefully it will not be approved]

The promise of protection is under siege. Elections have become proxy wars, with mining firms accused of bankrolling candidates and partylist groups. Watchdogs say the ballot is another tool to keep the mountains mined, the rivers drained, the ban undone.

The fate of Palawan’s 50-year moratorium lies in the balance: a moratorium passed after years of protest, now tested by legal precedent, political change, and councils willing to bend.

On paper, Palawan is protected until 2075. On the ground, the backhoes are waiting.

*We have requested an interview with Ipilan Nickel Corporation regarding the issues raised in this report and attempted to schedule an interview with company representatives. However, the company has not responded to our request.

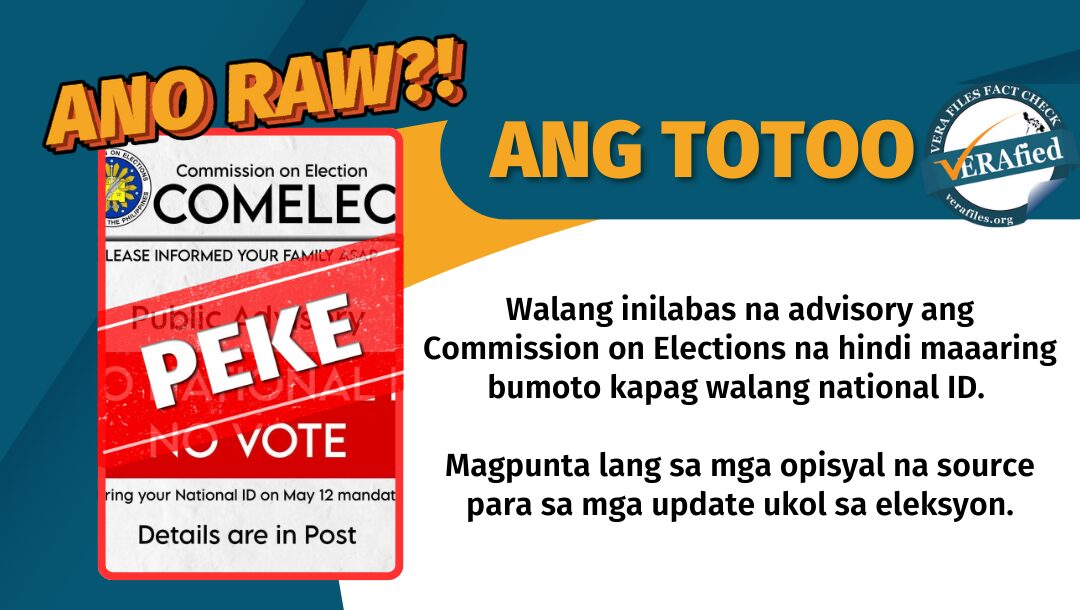

(This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network).