Just one-minute walk away from two private schools in Quezon City is a vape shop at the entrance of a basement parking lot in a five-storey commercial building. It may seem inconspicuous but the shop’s signage on the façade is hard to miss.

The building has several tenants, including a milk tea shop on the first floor. Before the pandemic, students in nearby schools spent time studying, accessing the internet, and meeting with friends there. It also has a dental clinic, a spa, and residential spaces on the higher floors.

Walk eight minutes more, roughly 540 meters down the road, another vape store is in the next barangay. It is about 350 meters from a public high school and an elementary school.

Executive Order (EO) No. 106 issued in February 2020 prohibits the sale, advertising and promotion of vapes, heated tobacco products (HTPs) or their components within 100 meters from any point in the perimeter of schools, public playgrounds, youth hostels and recreational facilities frequented by minors.

While the first store is in a commercial building on a busy street with a number of restaurants and coffee shops, the second is located in a residential area with food establishments nearby and is across a public playground.

Although it is outside the 100-meter distance from the nearby schools, both shops are still easily accessible and conveniently situated in areas frequented by students and other young people.

Selling e-cigarette products to persons aged 21 and below is unlawful under Section 144 (b) of Republic Act (RA) 11467, signed into law by President Rodrigo Duterte in January 2020, and Section 7 (c) of EO 106.

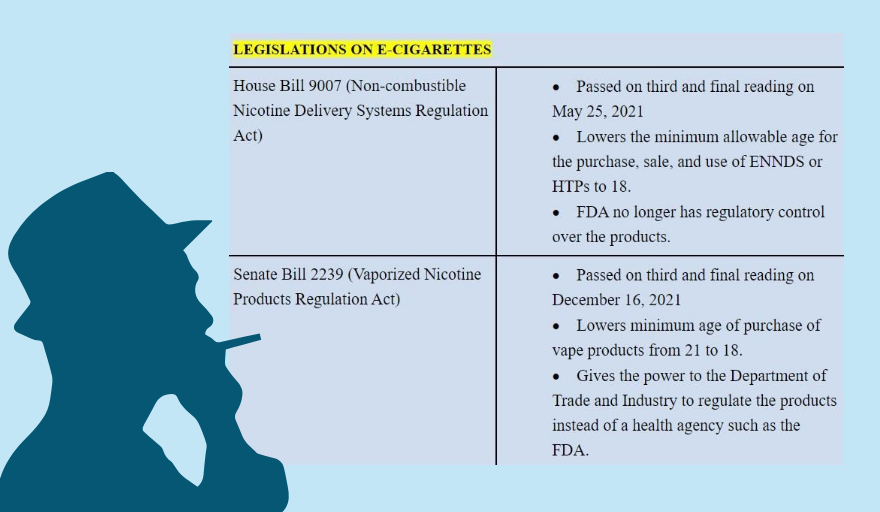

Health experts and advocates vigorously opposed the bills in Congress – Senate Bill (SB) 2239 and House Bill (HB) 9007 – that lower to 18 the minimum age of persons who can buy, sell or use novel tobacco products such as vapes and e-cigarettes.

(See VERA FILES FACT SHEET: What lowering age restrictions on e-cigarette smoking means for the youth)

The law increased the excise tax on the so-called “sin” products including Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems and Electronic Non-Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS/ENNDS) and HTPs, commonly known as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes or e-cigs).

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, ENDS are noncombustible tobacco products that come in the form of vapes, vaporizers, vape pens, hookah pens, e-cigarettes and e-pipes. These use e-liquids that may contain nicotine, as well as varying compositions of flavorings, propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, among other ingredients. The liquid is heated to create aerosol that the user inhales.

ENDS may be manufactured to look like conventional cigarettes, cigars, or pipes. Some are packaged in such a way that may be mistaken for pens or USB flash drives. Others are larger devices such as tank systems or mods.

These e-cigarettes contain toxic chemicals including nicotine, which is “highly addictive,” according to the World Health Organization. Other products that claim to be nicotine-free were found to also contain nicotine.

Vape products sold in the market are deceitful because of their looks, according to Dr. Rizalina Gonzalez, a pediatrician and chair of the Philippine Pediatric Society-Tobacco Control Advocacy Group (PPS-TCAG), in an interview with VERA Files.

“[It] really targets the children… When I didn’t know anything about vaping, I thought the flavoring was for cake. But now that I look at it, being next to the lighter, it really is deceiving,” she said, recalling an incident when she was taken aback to see vape flavors displayed in shelves at eye level, next to candies and other sweets, in a popular gasoline station along the South Luzon Expressway.

Researchers of VERA Files observed that in the Quezon City vape stores, the products are indeed displayed at the eye level of children, as Gonzalez mentioned. In view of these observations, the pediatrician underscored the need for stricter regulation to protect the youth from the harms of vaping.

Boosting sales thru social media

To stay in business during the community lockdowns due to the pandemic, the shops, which opened in 2018, activated their social media accounts to advertise their products.

On the day the VERA Files team was there, two riders were already waiting outside a few minutes before the first shop opened to pick up products ordered online.

Apart from checking out retail vape stores on busy streets, the VERA Files researchers also looked at popular online selling platforms, such as Shopee, Lazada, and the website of another Quezon City-based store that sells e-cigarettes, to find out how these are accessible to persons below 21 years old.

Upon entering the latter’s home page, a warning popped up that only those aged 21 and above can proceed and buy products online. However, one can easily sidestep this by clicking the “agree” button.

On Shopee, one of the researchers identified himself as an 18-year-old. On the first try, he was able to view the vape products available, added to cart some, and eventually bought a set of a compact-sized vape pod for P1,157. On the other shop’s website, the researcher managed to buy a tank-type device, which is customizable and bigger than the compact-sized pod, for P880.

In both instances, no age verification took place. He simply clicked the “agree” button.

A set of a compact-sized Relx vape pod and the cartridge bought on Shopee (left and middle), and the tank-type device bought on the website (right).

(See VERA FILES FACT SHEET: Smoke-free alternatives to cigarettes explained)

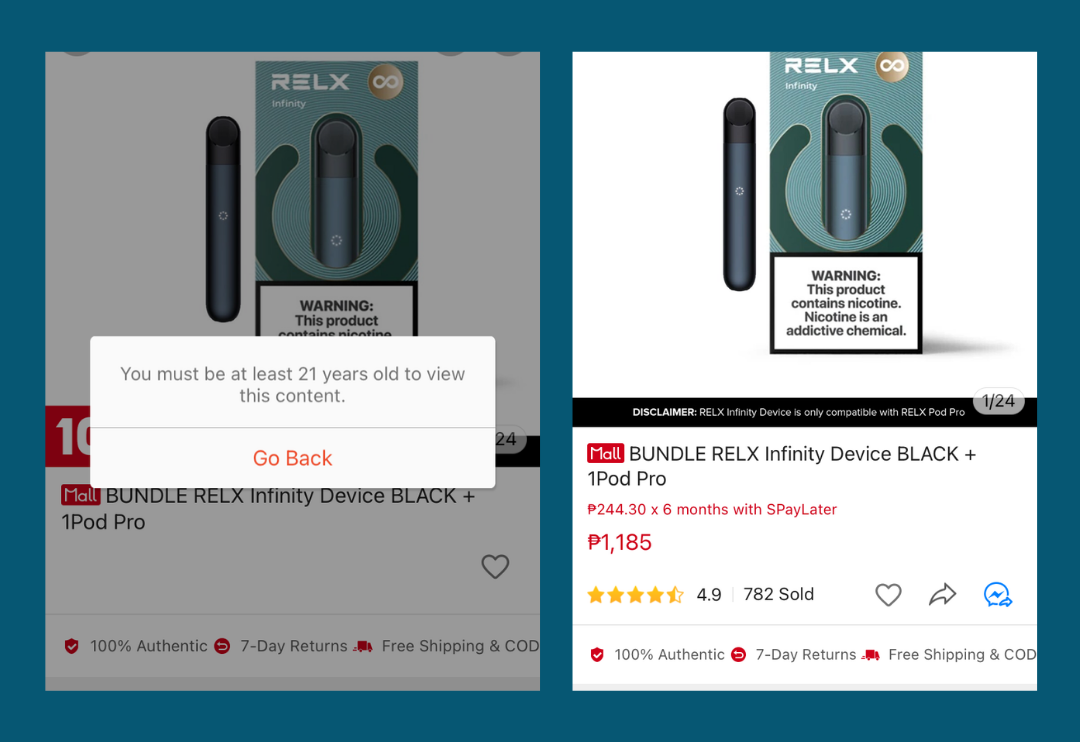

Two days later, the same researcher checked e-cigarettes on Shopee again and compared the prices of other vape brands. However, he was met with a warning similar to what was on the other store’s website. It said one should be at least 21 years old to view the products.

Not satisfied with the age verification mechanism of Shopee, both VERA Files researchers tried to view other products, using the same age, and got the same warning sign.

Screengrabs of a famous vape product sold on Shopee, taken on different dates

One of the researchers tried to change his age to 23 and was then able to view vape products and added them to the cart.

He also asked the seller of a well-known vape brand on Shopee if a person below the age of 21 can buy the products they sell online. He was told to try adding the products to his cart.

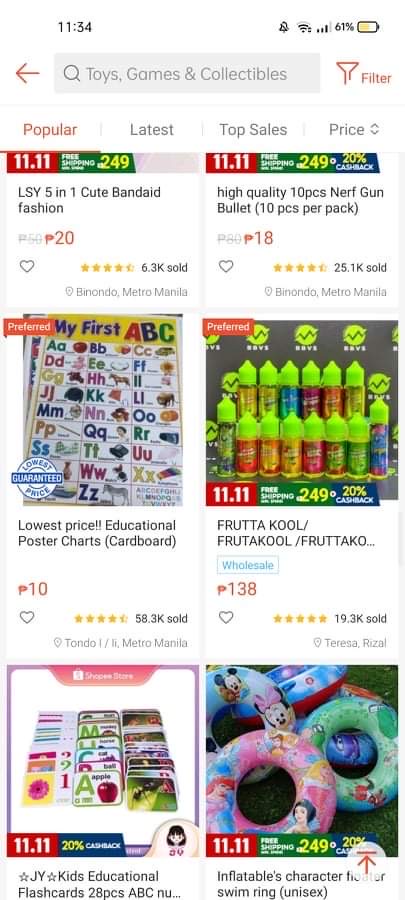

Certain e-juices for vapes are categorized under the “toys, games and collectibles” section on Shopee’s homepage.

Screengrab of an e-juice product categorized under the toys, games and collectibles on Shopee

Based on the researcher’s experience, Lazada hides results when searching for “vape,” but these products appear when other words are added to it. One of the researchers used “vape liquid.” Upon searching, the top listed products sell over a thousand pieces per month.

Like on Shopee, a prospective buyer can easily change his age on Lazada. One of the team members changed her age to 16, but was still able to buy vape pods, which were delivered just three days after checkout.

One vape pod was bought for P245. Another pod from a well-known brand was sold for P539.

Policy change shifts

Senate President Pro Tempore Ralph Recto, sponsor of SB 2239, argued that the bill conforms to the legal age, which is 18. For the products prohibited for sale to minors, retailers should have the responsibility to verify the age of buyers, he said.

In the first vape shop visited by VERA Files researchers, the age regulation was leniently observed. Although the storekeeper was aware that their products must be sold only to those aged 21 and above, he urged one of the researchers, who mentioned that he was only 19, to try vaping inside the store, an enclosed area. It has an exhaust fan anyway to vent out the smoke, he was told.

Section 3 of EO 26, an order providing a smoke-free environment, as amended by Section 7 of EO 106, prohibits “smoking/vaping within enclosed public places and public conveyances,” except in designated smoking//vaping areas.

Gonzalez warned that exhaust fans “have no use” because the chemicals from vape smoke can stick on surfaces for a long time.

“Third-hand aerosols are actually true. No matter how you scrub it with Clorox, it stays there for months on walls and hygroscopic surfaces,” Gonzalez said.

After several minutes in the store, the researcher bought pods and e-juices without being asked to present any identification card to check his age.

Recto, the bill’s sponsor, proposed during a Sept.13 Senate session that national government-issued IDs, such as passports and driver’s licenses, be required to verify one’s age.

But Gonzales argued that “there is no good enough way to regulate how old you are.” Teenagers, she said, can just pretend that they were told by adults to buy for them.

“Kids are smarter than us. They can always photoshop their face and make it old. They can always annotate their birth certificates,” she added.

‘Beginner-friendly’ flavors

Gonzalez warned that whatever form of nicotine is present in the product has the same effect on children, adding that e-juices come in thousands of flavors appealing to young people.

Most of the flavors are fruity, such as mango, melon, strawberry, and grape. There are also cotton candy, ube, mocha, cheesecake, bubble gum, and root beer. The variety of flavors and taste of the juices are obviously intended to lure young people to try vaping.

The sellers demonstrated how to use the products and even persuaded the researchers to try Chuckie – named after a chocolate milk brand – and strawberry flavors.

Flavors (from left to right): The flavors are seen at the eye level of children in the store, a relx pod, and a chocolate-flavored e-juice.

An indication that vaping is offered not to help tobacco smokers quit but to entice them to switch is the fact that some of the e-juice flavors, such as cheesecake, chuckie and crema, are being advertised as “beginner-friendly.”

Public health vs consumer product

Enticing flavors, peer pressure and curiosity are among the top reasons why many Filipino youths try and eventually use e-cigarette products regularly, Gonzalez said, citing initial findings in an ongoing study on the effects of vaping.

This was bolstered by the data in the 2015 and 2019 Global Youth Tobacco Survey, showing that while the number of cigarette smokers aged 13 to 15 years declined from 12% in 2015 to 10% in 2019, those using e-cigarettes increased from 11% to 14% during the same period.

The Department of Health (DOH) Epidemiology Bureau conducted the 2019 survey with 6,670 respondents aged 13 to 15 years.

Two senators – Cayetano and Sen. Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan – voted against SB 2239 on third reading. Only Cayetano consistently opposed the bill and said she was “beyond disappointed and beyond saddened” by its approval.

(See Senate OKs vape bill despite health concerns amid the pandemic)

Three days after the bill hurdled the Senate, the DOH slammed the “retrogressive” measure that “undermines the country’s progress in tobacco and control,” saying that it puts Filipino youth at risk.

If passed into law, the bill will “expose our youth to harmful and addictive substances by making vapor products enticing and easily accessible,” the press release read.

The bill stripped the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the regulatory authority over e-cigarettes and its components as a consequence of their reclassification as consumer products falling under the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI).

To health experts, the measure involves public health issues and should have stayed with the FDA for regulation, adding that people should not wait for vaping-related deaths to happen when parallel harms with traditional tobacco have already been proven in studies.

“The DTI in itself told us they can regulate the device – the heating element – but they cannot regulate the e-liquid, because it’s a chemical. It’s a health hazard. They need the FDA to regulate the e-liquid,” said Gonzalez.

“What we’re talking about here is a health issue. There should be health promotion, not industry promotion … More children will be in danger [if the bill becomes law],” she said.

After the sessions resume on January 17, the Senate and the House will harmonize their respective versions of the bill and ratify the conference committee report, then submit an enrolled copy to Malacañang.

Duterte, who expressed his anti-vaping stance strongly in 2019, has the option to sign it into law, allow it to lapse into law after 30 days, or veto the entire or parts of the proposed law.

The DOH, FDA, several medical professional organizations and health experts, youth groups and tobacco control advocates are counting on the president to stick to his anti-smoking and anti-vaping position and veto the proposed law that defies the policy he laid down in 2019.

This story is produced under the project ‘Seeing through the Smoke’, which has support from the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Inc (The Union) and Bloomberg Philanthropies.