While the Philippines continues to grapple with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), news about a new viral mutation that is said to be “globally dominant” and “more infectious” than the original have recently made the headlines.

The “new” mutation, which has been detected in some virus samples in the country, is known as the G614 strain.

What does this virus mutation mean for the country’s pandemic response? Is there any cause for alarm?

Here are five things you need to know.

1. What are viral mutations?

Mutations are a “natural part” of a virus’ life cycle. They pertain to permanent changes in the genetic sequence that can result from errors during the replication of genetic material (DNA or RNA), or through exposure to high-energy sources, such as radiation.

Viruses “constantly change as they reproduce in order to keep spreading into more cells,” according to a global team of public health experts and researchers convened by international nonprofit Meedan.

These changes (or mutations) create a “new, updated version of the virus,” called a “strain,” which may or may not be “functionally distinguishable” — like in the way it transfers from one person to another, how it leads to sickness, or how it responds to treatment — from the virus’ other forms. (See Mutations and misunderstandings: Are we now dealing with a supercharged COVID-19?)

Thus, tracking and studying the mutations of a virus — like SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19 — is important in the context of vaccine design, diagnosis, and implementing containment measures, according to the Philippine Genome Center (PGC).

2. What is the G614 strain?

In the case of the novel coronavirus, the change occurred in the 614th amino acid of the virus’ protein sequence, according to Los Alamos National Laboratory, a multidisciplinary research laboratory in the United States.

The original strain from Wuhan, China, carries aspartic acid (D) in its 614th amino acid, but the new strain has glycine (G). Hence, the mutation is named D614G, or simply the G614 strain.

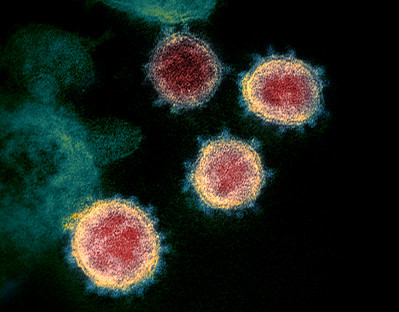

The change in the G614 strain is located in the spike region of the virus, or the spiky parts that latch onto cells it seeks to infect, according to Meedan’s team of experts.

A study published in the scientific journal Cell in July found that the G614 strain has more spike proteins, which, according to Meedan, means:

“…the virus is less likely to break off when it is trying to invade the human body, making it more likely to infect the exposed individual.”

Source: Meedan COVID-19 Expert Database, “What do we know about the new strain of this virus…,” Last modified on Aug. 26, 2020

The study, led by American biologist Bette Korber, based its findings on in vitro data, which are experiments done outside a living organism, usually in an artificial setting like a test tube or petri dish.

It was conducted on kidney cells from Vervet monkeys extracted in 1960, and from human cells picked in 1973 which were genetically altered to be more infected by any virus carrying the G614 strain, according to a National Geographic report that same month.

In the article, Korber said “[researchers] do not know” how the results of the study would translate to transmissibility in humans but that these are “currently being explored in several laboratories.”

3. Is it more infectious?

The Department of Health (DOH) has reiterated the PGC’s statement that there is “still no definitive evidence” to suggest that the G614 strain is, indeed, more infectious.

In an Aug. 18 interview with One News PH, PGC Executive Director Cynthia Palmes-Saloma said there is “no need to be alarmed” because:

-

- the site of mutation occurred in the hinge part of the spike region. Hence, it “does not have a lot of implications” on COVID-19 vaccine designs; and

- the mutation itself is “not new.” It has been discovered in Europe and the United States around March, but detected in the Philippines only in July.

The PGC, in its Aug. 13 bulletin, said the mutation “does not appear to substantially affect clinical outcomes.”

4. Is the G614 strain globally dominant? Is it also the most prevalent strain in the Philippines?

Several studies have shown that the G614 strain is, indeed, “the dominant strain in circulation around the world.” However, some scientists suggest that this may be due to the footprint of the pandemic, and not because the strain is more infectious.

In February, the concentration of COVID-19 cases shifted from China to Europe, noted a research by Nathan Grubaugh, an epidemiology professor at Yale School of Public Health, and his colleagues, also published in the Cell in July.

It said: “Over the period that G614 became the global majority variant, the number of introductions from China where D614 was still dominant were declining, whereas those from Europe climbed,” adding “this alone might explain the apparent success of G614.”

In the Philippines, the PGC said in its Aug. 13 report that, although they detected the strain in nine out of nine randomly selected samples from Quezon City, this is not representative of the mutational landscape of the country.

DOH has said it is continuously monitoring mutations, through genome sequencing studies produced by the PGC and the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM), to calibrate and improve the country’s current containment, diagnostic, and therapeutic strategies.

This can “provide the necessary data to determine patterns of virus circulation in the country” and can “complement contact tracing and identify cases that belong to the same transmission clusters and trace sources of infection,” Health Undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire told VERA Files in an email interview.

The PCG’s most recent study traced three possible sources of infection in the country:

-

- foreign visitors from China in early January;

- repatriated seafarers from the M/V Diamond Princess coronavirus outbreak in February; and

- European sources, possibly from repatriated tourists and overseas Filipino workers returning from Europe and the Middle East in May.

In an interview with Manila Bulletin on Aug. 25, Saloma said the PGC will study 900 more samples taken from March to October from all over the Philippines. The center aims to complete the research by October.

5. What are the best courses of action now that we know of the strain?

Regardless of the virus variant, Vergeire reiterated that “preventive measures to protect the public against contracting COVID-19 are the same.”

The public must continue to wear face masks and face shields, wash hands with soap and water, maintain six feet physical distance, and keep accessing accurate information to lessen the transmission of the virus.

Apart from extensive research and amplified contact tracing, DOH said there is also a need to “strengthen surveillance and control measures” at the country’s borders. This may limit both the spread of the virus and the introduction of “potentially more virulent and/or infectious” variants to the population.

ERRATUM: This piece was updated to correct the spelling of American biologist Bette Korber. The original article misspelled the the scientist’s last name as “Krober”. We apologize for the mistake.

Sources

World Health Organization, Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Jan. 30, 2020

Philstar.com, New coronavirus mutation found in the Philippines, Aug. 17, 2020

GMA News Online, More infectious, dominant novel coronavirus strain detected in Philippines, Aug. 16, 2020

Nature, We shouldn’t worry when a virus mutates during disease outbreaks, Feb. 18, 2020

Nature, Genetic Mutation, Accessed Sept. 3, 2020

Khan Academy, Evolution of viruses, Accessed Sept. 3, 2020

Nature Scitable, Mutations Are the Raw Materials of Evolution, Accessed Sept. 1, 2020

Learn About COVID-19, What do we know about the new strain of this virus that is more infectious than the first strains?, Aug. 26, 2020

Learn About COVID-19, About, Accessed Aug. 26, 2020

UK Research and Innovation, Are there different strains of the SARS-CoV-2 virus circulating?, June 10, 2020

VERA Files, Mutations and misunderstandings: Are we now dealing with a supercharged COVID-19?, May 21, 2020.

Philippine Genome Center, Bulletin No. 1, Aug. 13, 2020

Los Alamos National Laboratory, Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Spike mutations, Accessed Sept. 1, 2020

Cell, Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus, July 2, 2020

The Marshall Protocol Knowledge Base, Differences between in vitro, in vivo, and in silico studies, Sept. 1, 2019

National Geographic, Why This Coronavirus Mutation Is Not Cause For Alarm, July 15, 2020

Department of Health, PGC, RITM Confirm G614 Variant Presence in the Country, Aug. 18, 2020

Philippine Genome Center, Bulletin No. 1, Aug. 13, 2020

One News PH, Mutated coronavirus strain found in PH “not new” —PGC, Aug. 17, 2020

ScienceDirect, A genetic barcode of SARS-CoV-2 for monitoring global distribution of different clades during the COVID-19 pandemic, Aug. 22, 2020

bioRxiv, D614G mutation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein enhances viral infectivity, July 6, 2020

Cell, Making Sense of Mutation, July 2, 2020

Philippine Genome Center, Bulletin No. 2, Aug. 26, 2020

medRxiv, Analysis of SARS-COV-2 Genome Sequences from the Philippines: Genetics Surveillance and Transmission Dynamics, Aug. 25, 2020

Inquirer.net, DFA: 49 Filipinos aboard Diamond Princess test positive for COVID-1, Feb. 22, 2020

CNN Philippines, 442 Filipino evacuees from Diamond Princess cruise ship sent home, March 12, 2020

Manila Bulletin, Filipinos on cruise ship returning on Feb. 25, Feb. 23, 2020

Manila Bulletin, Filipino scientists to expand study on coronavirus strain mutation, Aug. 25, 2020

(Guided by the code of principles of the International Fact-Checking Network at Poynter, VERA Files tracks the false claims, flip-flops, misleading statements of public officials and figures, and debunks them with factual evidence. Find out more about this initiative and our methodology.)