Calbayog, known as the “City of Waterfalls,” is facing an important decision: how to strengthen energy security through wind power while ensuring long-term protection of its water sources, forests and communities.

At the heart of the controversy is a plan to build 38 large wind turbine generators, 13 of which will rise inside a strict protection zone of the Calbayog Pan-as Hayiban Protected Landscape, the city’s main watershed and a recognized biodiversity haven.

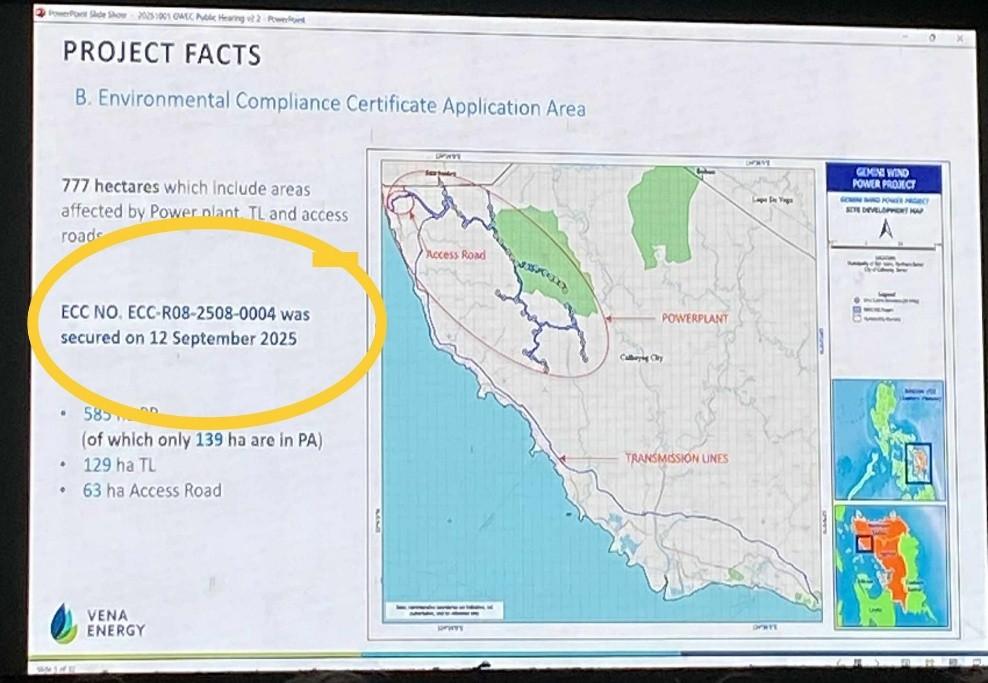

The P20.2-billion project by Gemini Wind Energy Corporation, a local unit of Singapore-based Vena Energy, promises 304 megawatts of renewable energy by 2026, potentially supporting regional development and contributing to the Philippines’ clean-energy targets.

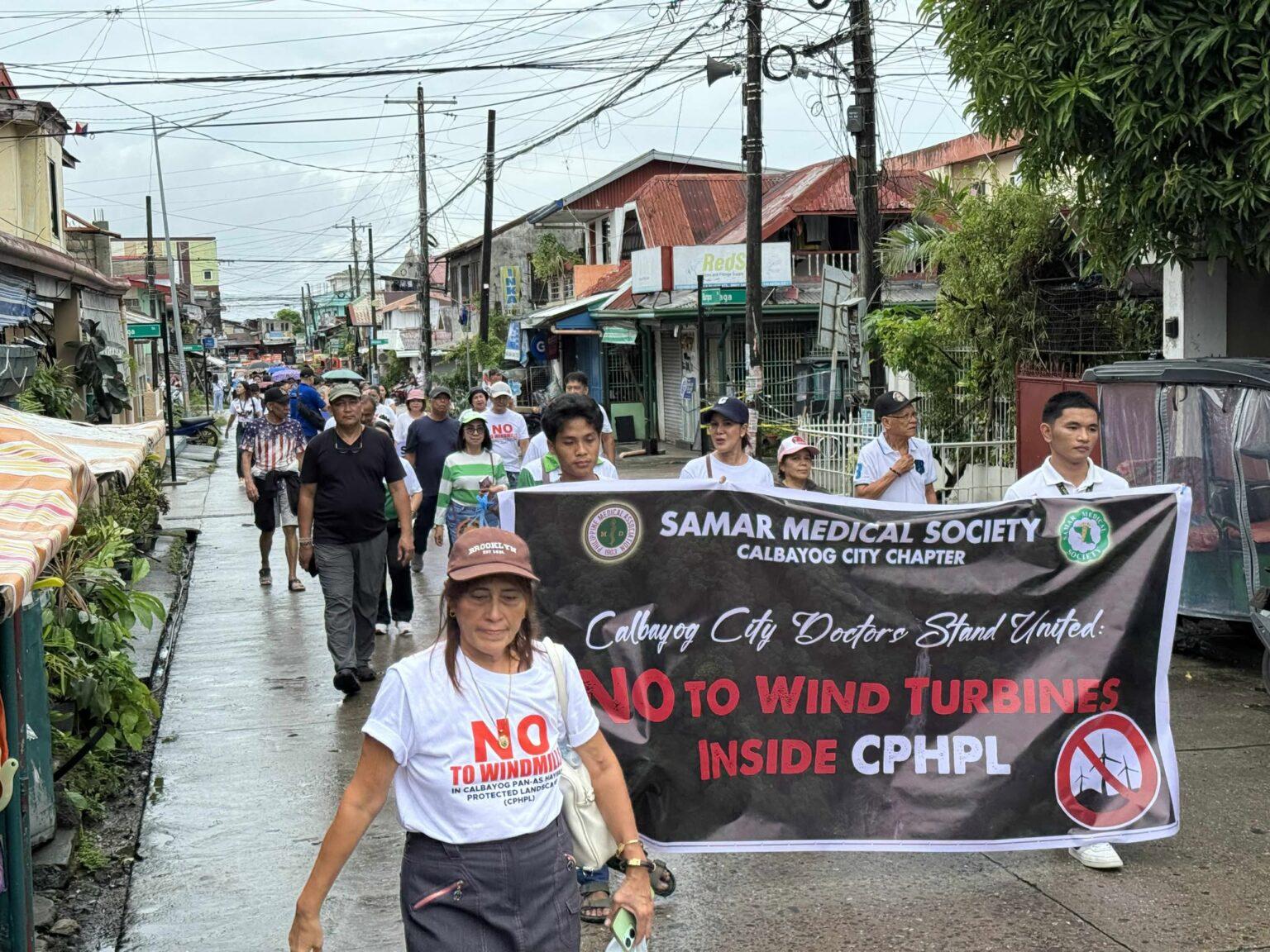

However, community groups, local officials and environmental advocates caution that the project may risk long-term water security, forest integrity and public trust, if not carefully planned.

The project spans Calbayog City, Samar and Northern Samar. It was approved under the government’s Green Energy Auction Program in 2023 and recognized by the Department of Energy as a project of national significance identified as a strategic investment by the Board of Investments.

Vena Energy is one of Asia’s largest renewable energy independent power producers. In the Philippines, it operates six power plants with a combined capacity of 330.80 MW across Negros Occidental, Rizal, Leyte, Ilocos Norte and Bukidnon.

Yet despite these credentials, questions over zoning changes, environmental safety and transparency have prompted local sectors to call for a more inclusive and science-based approach—one that aligns development goals with the city’s ecological responsibilities.

A watershed threatened

Established in 1998 through Proclamation No. 1158, the CPHPL covers more than 5,000 hectares and supplies freshwater to Calbayog and surrounding barangays. Its 34 waterfalls, dipterocarp forests, century-old trees, caves, rivers and hot springs make it an ecological and cultural anchor for the region. It is also home to endangered species and serves as a natural buffer against landslides and flooding—issues that have increasingly affected surrounding communities during heavy rains and typhoons.

It is among the 94 protected areas covered under the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018 (Republic Act No. 11038), safeguarded for ecological integrity and hydrological importance.

Because of its hydrological value, many residents fear that heavy construction in steep slopes or strict protection zones may heighten risks. Others, however, see renewable energy as a pathway toward lower power costs, job creation and long-term energy stability.

Vena Energy, GWEC’s mother company, is also facing backlash for a similar wind project in the Masungi Georeserve in Baras, Rizal province, where 16 turbines would be built inside the strict-protection zones.

Wind projects in Mt. Banahaw, Quezon and Paete, Laguna have likewise become centers of controversy lately, with biodiversity loss, water resource management and flooding among the primary concerns.

In the Calbayog project, Vena Energy has assured compliance with environmental laws, stating only a small portion (0.48%) of the watershed will be directly affected.

Wind energy potential and community questions

Project documents show that 24 turbines are planned outside the protected area, while 13 fall within strict protection zones, where infrastructure is normally restricted. Construction of the 38th turbine in San Isidro, Northern Samar, has already begun, signaling rapid expansion of wind-energy activities in this regional corridor.

Supporters highlight expected benefits: local taxes and fees, jobs for residents, and social development programs. Yet environmental experts, including Phil Harold Mercurio of the Samar Island Heritage Center Inc., warn that road cuts, tree clearing, and drilling may cause “irreversible ecological damage” and increase the risk of rockslides, flooding, and sedimentation.

Residents from Oquendo and Tinambacan report early signs of watershed stress—clogged waterfalls, flooding in low-lying barangays like Sigo and Cag-anahaw, and mudslides cascading from the mountains following heavy rains.

The Calbayog Water District, which provides water to over 19,000 connections, confirms that supply drops sharply during storms and remains inconsistent in several communities. Even on normal days, outages persist in several barangays.

Regional Operations head Fernan Barry Bohol said they supply about 14 million liters per day to residential and commercial consumers, yet still struggle to meet demand. The fear among communities is simple: If the watershed is destabilized, Calbayog’s water system collapses.

These concerns have led many residents to ask for clearer explanations, updated maps and more transparent coordination among national agencies, barangay leaders and civil society groups.

Zoning changes and questions of public participation

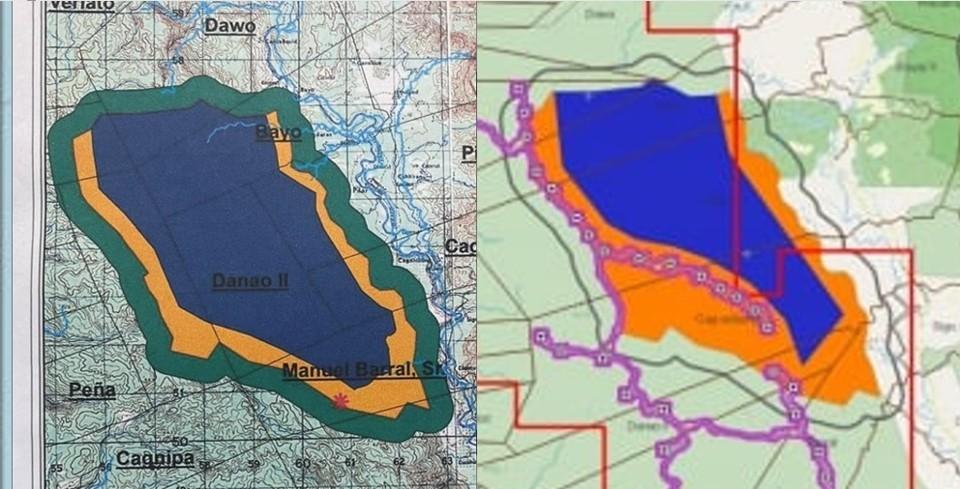

Why was the wind farm moved deeper into the watershed? Opposition groups say the answer lies in the rezoning of the CPHPL.

A new map approved by the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) expanded the multiple-use zone and reduced the strict protection zone, effectively opening previously off-limits areas to turbine installation. Critics call it a “catered map,” while the DENR maintains that the process followed legal procedures.

DENR–Samar Protected Area Superintendent Dennis Delos Santos, however, maintains the process was legitimate and approved by the central office.

“Hindi ibig sabihin na protected area ay bawal na talaga magtayo ng turbina,” he said during a public hearing.

(Just because it is a protected area does not mean turbines can never be built there.)

A turning point: Toward transparency and collaborative planning

The developer also secured a Special Use Agreement in Protected Areas under Republic Act No 11038 (Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018, which allows certain regulated activities within protected landscapes.

Some barangay officials in Cag-anibong and nearby areas said they endorsed the project believing it had already been approved at higher levels, but testimonies from residents reveal concerns about pressure, insufficient consultation and a feeling of being left out of key decisions.

Barangay Chairman Nestor Malwinda defended their endorsement. “If it’s for the welfare of the community, why don’t we support it? The national agencies are here—they will not endanger us.”

Rebecca Hatakenaka of Manuel Barral Sr. disclosed that their endorsement was instructed “from above,” while Pilar resident Orcisino Anquilan said most in his barangay were against the project but felt powerless.

A turning point: Calls for transparency and better processes

The issuance of the Environmental Compliance Certificate by the DENR-EMB Region 8 last Sept. 12 triggered renewed calls for dialogue. Both Calbayog Mayor Raymund Uy and Gov. Sharee Ann Tan acknowledged the need for clearer explanations on zoning changes, community involvement, and technical assessments.

During a recent dialogue, stakeholders agreed to: identify three alternative sites outside the protected landscape, restore the original 2022 CPHPL management zones based on the 2022 National Mapping and Resource Information Authority data, relocate the developer’s office to Calbayog and prioritize local hiring, ensure that host communities receive a fair share of user fees and power-generation revenues, and strengthen community participation in future decisions.

These steps mark an important shift toward a more transparent, inclusive and science-informed process.

Science-based pathways to balance energy and ecology

To address uncertainties, the city government agreed to fund a biodiversity audit, with technical assistance from the Visayas State University Biodiversity Research Center. The governor also proposed a parallel assessment by the University of Santo Tomas.

Renewable-energy advocates note that clean energy remains a vital national priority. Former Calbayog Mayor Mel Sarmiento’s earlier feasibility assessments identified alternative ridge areas planted with coconuts — not within strict protection zones — as technically viable for wind farms, with access to transmission lines and lower ecological impact.

“My vision prioritized ecological and hydrological safeguards. The plan minimized impact on protected areas while preserving water security for future generations,” Sarmiento said.

Exploring such options could reduce risks to the watershed while preserving the economic benefits of the wind investment projected at ₱20 billion.

Constructive solutions require rebuilding trust among communities, government agencies and project proponents. Key steps repeatedly suggested by stakeholders include:

- ensuring all zoning changes follow due process and public disclosure

- involving local universities, hydrologists, and environmental scientists in evaluating risks

- establishing clear channels for civil society and indigenous groups to participate

- providing barangays with capacity-building support to understand technical environmental documents

- ensuring that agreements on user fees, energy shares, and community benefits are transparent and well communicated.

Finding a middle ground

While opinions differ, many citizens and experts agree on a shared goal: Calbayog needs both water security and sustainable energy.

A possible compromise—relocating turbines outside strict protection zones while maintaining the project’s clean-energy promise —is now under consideration.

The governor has expressed willingness to work with stakeholders and explore alternative sites. The city government has paused activities in the strict protection zone until scientific studies are completed.

What comes next?

The coming months will be critical as: biodiversity audits are completed, alternative sites are evaluated, the Protected Area Management Board undergoes review, and independent technical assessments guide the final decision.

This is no longer a debate over “wind turbines versus waterfalls.” It has become a broader conversation about how Calbayog City can pursue clean energy, protect its water sources and ensure transparent governance at the same time.

By grounding the decisions in science, community participation and long-term sustainability, Calbayog — a first class component city in Samar and the largest in Eastern Visayas —has an opportunity to become a national model for responsible, inclusive and future-ready development.

*Gina Dean and Lourence Mae Alkuino, news anchors of 89.5 Kauswagan Radyo and Development Communication instructors at the Northwest Samar State University, are VERA Files fellows under the project Climate Reporting: Turning Adversities into Constructive Opportunities.

This story was produced with the support of International Media Support and the Digital Democracy Initiative, a project funded by the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

The views and opinions expressed in this piece are the sole responsibility of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, and International Media Support.