Blogger Sass Rogando Sasot, a vocal supporter of President Rodrigo Duterte, made at least seven inaccurate claims about the West Philippine Sea issue as tensions in the region rise with the continued unauthorized presence of Chinese vessels in the Philippines’ maritime areas.

In a 2,238-word Facebook (FB) post on April 13, Sasot wrote a primer about the South China Sea dispute between the Philippines and China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA).

In its July 2016 ruling, the arbitral tribunal held that there was “no legal basis” behind China’s nine-dash line claim, which covered almost 80% of the entire South China Sea. It also declared certain maritime features to be within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ). (See VERA FILES FACT CHECK: Duterte shifts from ‘invoking’ to ‘ignoring’ the PCA ruling)

A reader asked VERA Files Fact Check to look into Sasot’s post, which has been shared at least 8,500 times and garnered around 12,400 interactions as of April 28. Among the blogger’s several claims, three are false, two are misleading, and two are missing important context.

Read on to know more about each claim:

On the ‘limited’ jurisdiction of a coastal state in its EEZ

The rights and duties of a coastal state, like the Philippines, in its own EEZ under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) are not limited only to the three points Sasot mentioned.

A coastal state, first and foremost, has sovereign rights to explore, exploit, conserve, and manage the natural resources in its EEZ, and to other activities concerning “the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone.” This includes the production of energy from the water, currents, and winds, as stated in Article 56 of the convention.

In the exercise of such right, it may impose “necessary” measures to “ensure compliance with the laws and regulations” it has adopted — including boarding, inspection, arrest, and judicial proceedings — that conform with UNCLOS.

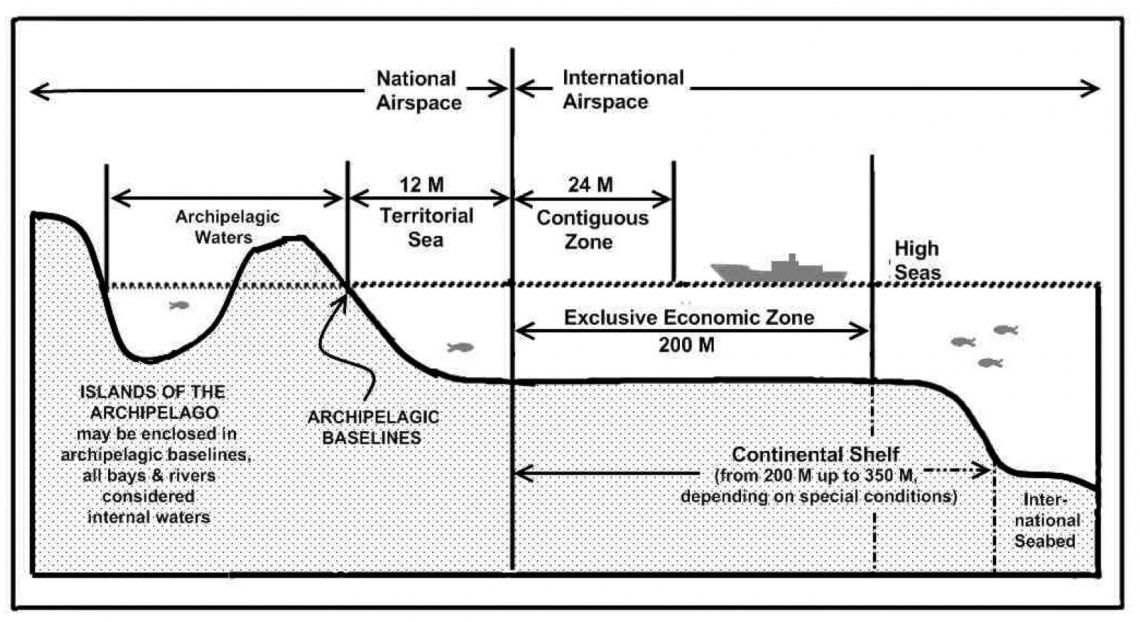

UNCLOS maritime zones (Source: The West Philippine Sea: A Territorial

and Maritime Jurisdiction Disputes from a Filipino Perspective)

An EEZ covers the area beyond and adjacent to a coastal state’s territorial sea, but may not extend farther than 200 nautical miles from its baselines. (See VERA FILES FACT SHEET: West Philippine Sea tensions and the Arroyo presidency)

On the coverage of coastal state’s EEZ rights

Article 56 of UNCLOS — which details the rights, jurisdiction, and duties of a coastal state in its EEZ — clearly lays out that a coastal state has sovereign rights to exploit and manage both living and non-living resources of the “waters super adjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil.”

On the Aquino administration’s ‘propaganda’ on the West Philippine Sea

The Aquino Administration did not equate the West Philippine Sea to the South China Sea. The West Philippine Sea refers only to the maritime areas the country claims.

Under Administrative Order (AO) No. 29, signed by former president Benigno Aquino III in September 2012, the “maritime waters in the western side of the Philippine archipelago” was officially renamed as the West Philippine Sea. This includes the Luzon Sea, the waters “around, within, and adjacent to the Kalayaan Island Group,” and Bajo De Masinloc (international name: Scarborough Shoal).

In its preamble, AO 29 pertains only to the maritime areas that fall under the country’s jurisdiction, including its 200-nautical mile EEZ, as defined and dictated by local and international laws. It made no claim whatsoever to the entire South China Sea.

In a media interview days after signing AO 29, Aquino even “clarified” that it covered only “portions of the South China Sea,” according to a report by Inquirer.net.

Part of the article, published on Sept. 13, 2012, read:

“‘It is important to clarify which portions we claim as ours versus the entirety of the South China Sea,’ Mr. Aquino said, explaining to reporters the need to officially rename the area because some countries call it by other names.”

On the PCA ruling on who ‘owns’ the South China Sea

Sasot said this immediately after she made the false claim that the Aquino administration had equated the entire South China Sea to the West Philippine Sea.

The Philippines is not claiming “ownership” nor jurisdiction over the entire South China Sea, and also did not ask the arbitral tribunal to declare such.

The court, however, found that there is:

“…no legal basis for any Chinese historic rights, or sovereign rights and jurisdiction beyond those provided for in [UNCLOS], in the waters [and resources] of the South China Sea encompassed by the ‘nine-dash line’.”

But China, to this day, snubs the arbitral ruling and continues to seize and exercise control over various features within the “nine-dash line.” (See VERA FILES FACT CHECK: Duterte shifts from ‘invoking’ to ‘ignoring’ the PCA ruling; Carpio: PH must work with other countries vs China over disputed territory)

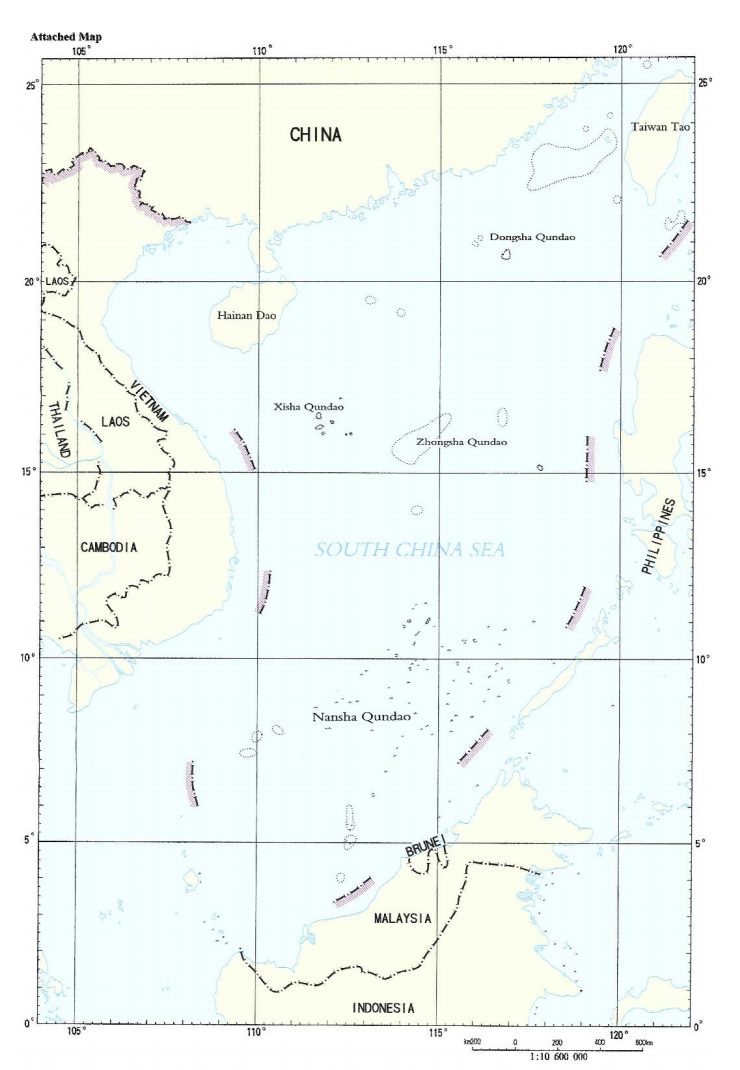

A map of China’s nine-dash line covering almost the entire South China

Sea, which the arbitral tribunal found to have “no legal basis” in its

2016 ruling. Screenshot from the South China Sea Arbitral Award

On driving away China from PH EEZ

In its 2016 ruling on the South China Sea dispute, the arbitral tribunal held that China “had violated the Philippines’ sovereign rights” in its EEZ by:

- interfering with the Philippine fishing and petroleum exploration;

- constructing artificial islands; and,

- failing to prevent Chinese fishermen from fishing in the zone.

In an April 16 FB post debunking Sasot’s claims point-by-point, Jay Batongbacal, director of the Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea at the University of the Philippines, said this meant “mali sila (China), wala silang karapatan manatili [doon] kung ayaw natin (they are wrong, they don’t have the right to stay [in our area] if we don’t want them to).”

As a party to UNCLOS, China, in the exercise of its rights, must “comply with the laws and regulations” adopted by the Philippines (that are in accordance with the convention) within the latter’s EEZ, as stated in Article 58.

On the obligation to share living resources in EEZ

UNCLOS, indeed, obliges a coastal state to give other states access to its fishing surplus if it does not have the capacity to harvest the total allowable catch of living resources in its EEZ.

However, nationals of other states fishing in the EEZ of a coastal state must still “comply with the [latter’s] conservation measures and with other terms and conditions established in [its] laws and regulations” consistent with the convention.

This may include the licensing of fishermen, fishing vessels and equipment, and the payment of fees and other forms of remuneration; regulating seasons and areas of fishing; and specifying information required of fishing vessels, among others.

On the other hand, the 1987 Philippine Constitution explicitly mandates the state to:

“…protect the nation’s maritime wealth in archipelagic waters, territorial sea, and [EEZ], and reserve its use and enjoyment exclusively to Filipino citizens.”

Source: Official Gazette, 1987 Constitution – Article XII, Section 2

This is further reiterated in Republic Act 8550 or the Philippine Fisheries Code, which states that the “use and exploitation of the fishery and aquatic resources in Philippine waters (including the country’s EEZ and continental shelf) shall be reserved exclusively to Filipinos.” (See VERA FILES FACT CHECK: Allowing China to fish in PH EEZ violates Constitution, local laws; VERA FILES FACT CHECK: Malacañang backtracks on Duterte’s ‘verbal fishing deal’ with China)

On PCA ruling on the Spratlys

It is true that the arbitral tribunal did not decide on which state has “ownership” over the entire Spratly Island Group, nor over the high-tide maritime features in it. The South China Sea arbitration dealt only with the nature of the disputed maritime features in the area, and the maritime entitlements they are able to generate under UNCLOS.

Thus, the tribunal found that “none of the Spratly Islands is capable of generating extended maritime zones (EEZ and continental shelf),” and that it “cannot generate maritime zones collectively as a unit.”

“This may prove to be an important factor if and when the question of who owns which island in the island chain is actually submitted to another international arbitration proceeding,” lawyer Romel Bagares, who teaches international law at Lyceum Philippines University College of Law, wrote in a 2016 commentary at VERA Files.

China continues to insist on its “indisputable sovereignty” over the entire Spratly Island Group, which it refers to as Nansha Islands. (See VERA FILES FACT CHECK: Apology from Chinese association falsely claims Recto Bank is China territory)

The Philippines, on the other hand, continues to assert its claims over the Kalayaan Island Group, which is composed of more than “50 features and their surrounding waters” in the Spratlys. The area is believed to be “both economically valuable and strategically important for the purposes of national security,” as stated in a 2013 primer on the West Philippine Sea by the Institute for Maritime and Ocean Affairs.

Bagares, however, told VERA Files Fact Check in an email interview that, in light of the arbitral award, the Philippines “needs to redraft” its set baselines around the Kalayaan Island Group, as stated in Presidential Decree 1596 (issued in 1978), “because the arbitral tribunal had, in fact, declared these baselines incompatible” with UNCLOS.

“This … is an important point that many policy-making sectors in government apparently continue to miss or to misunderstand,” he added.

Nevertheless, having found that none of the features claimed by China in the Spratly Island Group was capable of generating its own EEZ, the tribunal declared certain low-tide features — such as Panganiban (Mischief) Reef and Ayungin (Second Thomas) Shoal — to be “part of the [EEZ] and continental shelf of the Philippines.”

Sources

For the Motherland – Sass Rogando Sasot Facebook page, MGA KATANUNGAN TUNGKOL SA PHILIPPINES VS. CHINA ARBITRATION CASE (archived), April 13, 2021

Permanent Court of Arbitration, PRESS RELEASE: SOUTH CHINA SEA ARBITRATION, July 12, 2016

Permanent Court of Arbitration, South China Sea Arbitral Award, July 12, 2016

United Nations, UNCLOS, Accessed on April 21, 2021

United Nations, UNCLOS: PART V EXCLUSIVE ECONOMIC ZONE, Accessed on April 21, 2021

Official Gazette, Administrative Order 29, Sept. 5, 2012

Official Gazette, Presidential Decree 1596, June 11, 1978

Institute for Maritime and Ocean Affairs, The West Philippine Sea: A Territorial and Maritime Jurisdiction Disputes from a Filipino Perspective, July 15, 2013

Inquirer.net, It’s official: Aquino signs order on West Philippine Sea, Sept. 13, 2012

Jay Batongbacal Facebook account, “I’ve been asked for comments about this particular post twice on different groups, so let me just put them here…,” April 16, 2021

United Nations Treaty Collection, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Accessed April 27, 2021

Official Gazette, 1987 Constitution – Article XII, Section 2

Official Gazette, Republic Act 8550, Feb. 25, 1998

Department of Foreign Affairs, DFA PROTESTS ANEW ILLEGAL PRESENCE OF CHINESE VESSELS IN PHILIPPINE WATERS, April 23, 2021

(Guided by the code of principles of the International Fact-Checking Network at Poynter, VERA Files tracks the false claims, flip-flops, misleading statements of public officials and figures, and debunks them with factual evidence. Find out more about this initiative and our methodology.)